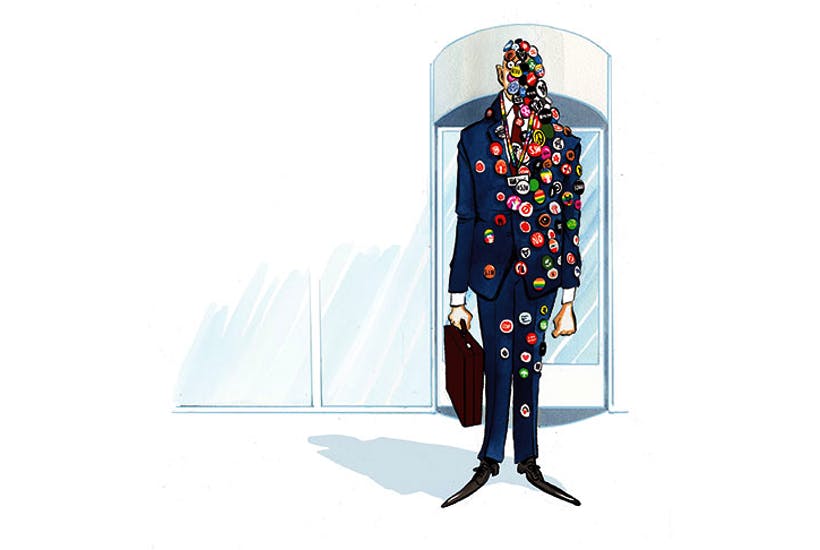

The woke businessman, like the woke prince and princess, is an ambiguous figure. Being woke, after all, involves a contempt for profits and big business, as for social hierarchy. I first noticed this uneasy phenomenon many years ago when I attended a lunch in the City at which Paul Polman, the then chief executive of Unilever, read us a moralistic lecture about European integration, greenery and how ‘I agree with Mahatma Gandhi: you must be the change you want to see in the world’. I found it intensely annoying to be told how to be good by someone much richer than myself. Last year, the change Mr Polman wanted to see of moving Unilever’s HQ from London to Rotterdam failed, and he was out. Now his successor, Alan Jope, is using a similar patter. He is keen on what he calls ‘purpose’ in brands, by which he seems to mean persuading young people that things his company makes are virtuous. If brands do not ‘contribute meaningfully to the world or society in a way that will last for decades’, they must go.

This doctrine may apply to Unilever’s Marmite. Surely Marmite’s meaningful contribution to the world since its invention in 1902 is that people like it and find it cheering. It may also be true that, as it used to say rather cautiously on the pot, ‘Within the limits of the amount consumed, Marmite is a useful source of natural protein’, but this is not the secret of its success. If it is a choice between saving Marmite and ‘saving the planet’, one instinctively favours the former. ‘Principles are only principles,’ Mr Jope goes on, ‘when they cost you something.’ If I were a shareholder of Unilever, I would remind him of the principle of maximising value for the people who own the company. How much are Mr Jope’s principles costing him? At present, he earns €1.45 million a year, plus a targeted annual bonus of 150 per cent of fixed pay (which could go up to 225 per cent), plus share arrangements.

This article is an extract from Charles Moore’s Spectator Notes, available in this week’s magazine.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in