Before Boris Johnson became Prime Minister there was widespread expectation that his government would be chaotic. It was thought that he would be good at articulating the broad sweep of government policy, but that his administration would quickly sink into turmoil. In the event, the opposite has happened. Three weeks on, the government appears to be running with almost military precision. Preparations for no-deal Brexit seem to be well under control, to the alarm of Philip Hammond, who had thought the task impossible.

Yet the Prime Minister himself seems to have gone underground. He is not on holiday — his government is working all hours. But he has not been as big a feature of it as many expected. His strategy of ducking interviews, which to some people’s surprise worked well while he was campaigning for the leadership, seems to have become permanent. He has developed a Corbynite aversion to the Today programme and has made few public appearances, emerging only for photocalls with his girlfriend, Carrie Symonds, and for a prison visit this week. He has used social media sporadically, but nothing else. No speeches. No clues, to Britain or beyond, as to the direction of his government.

Boris risks depriving his government of what should be one of its greatest strengths — his ability to communicate ideas and broadcast his optimistic vision of a liberal Brexit. His criticism of Theresa May was that, to her, Brexit was all about the process — and nothing about what comes beyond it. A great many people still have reasonable concerns about (as Philip Hammond put it) Britain turning in on itself after Brexit. We are told that a Johnson premiership is about the opposite: making new alliances and friends. But, at present, we have heard little from the PM himself.

The first weeks of the Boris government have passed off without incident and without the disorganisation that afflicted the early period of his time as Mayor of London. This is in large part down to the role of Dominic Cummings. He is doing what he does best: reading the public mood, getting inside the heads of his opponents and devising strategy accordingly.

As Cummings has correctly worked out, there is a large appetite, both among the public and business leaders, to end the uncertainty and conclude Brexit. He has also worked out that a government that looks ready for a general election is less likely to be threatened by one.

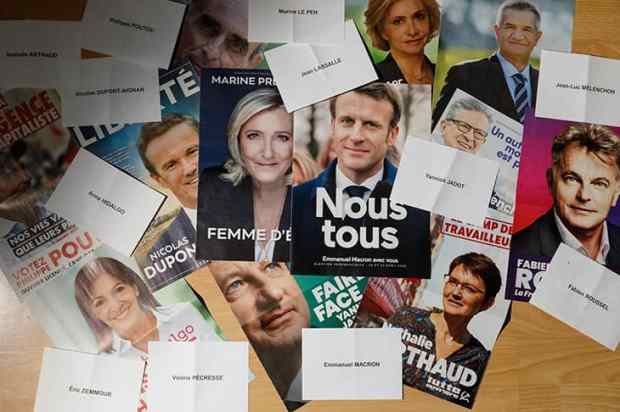

The rearguard Remain campaign has been wrong-footed. Its most recent attempts to stop Brexit — a vote of no confidence in the government and a legal action in the Scottish courts launched this week — look to have fading public support and to be too late to thwart Britain’s exit on 31 October, although a confidence vote in early September could well precipitate a general election soon after that date. But what no adviser can provide — and which will be so vital if an election occurs — is a political vision to be communicated with the public. That is Boris’s job alone, and one that at present he is neglecting.

We know the ingredients for such a vision exist because Boris has spent the past two decades fine-honing his brand of liberal conservatism. We know he believes in free markets, in liberal immigration rules for those who are prepared to work and obey the law. We know he believes in deregulation and trusting people to make their own decisions over their lives because he has articulated this many times. So now that he has been granted his lifetime’s ambition to lead the country, it would be a shame if his vision were to become blurry.

There was his commendable announcement on the steps of Downing Street that EU citizens already resident in Britain will continue to enjoy their rights, whatever happens with Brexit negotiations. But his equally admirable policy of granting an amnesty to illegal migrants who have been living in Britain under the radar for many years seems to have been shunted into the sidings, perhaps out of fear of offending Brexit party voters. Instead, we have had the announcement of a tougher penal policy in which serious criminals will be made to serve much more of their sentences — good in itself, but which can come across too much as a pitch to the authoritarian right if not balanced by other liberal policies.

For the next 11 weeks Brexit will inevitably dominate, but what then? By November Dominic Cummings could well be gone from government, taking his strategic skills with him. Boris may find himself fighting an election, whether he wants one or not. He cannot afford to do what May did, and what cost her a majority — shun TV interviews and debates in the false belief that live exposure offered more opportunity to lose votes than to win them. By accident or design, Cummings has taken all the flak so far. This might suit the PM, but he should not get used to it.

His political career is built upon his two successful terms as London Mayor. He must not forget how he achieved the task of winning over a Labour city: it was not through shielding himself from the public but by thrusting himself upon it, with courage and verve. His declared mission is not just to do Brexit but to unite the country. It is a job that cannot be devolved.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in