Last year I found myself giving a lecture in Helsinki. When I came to the end, I asked the audience if there were any questions. There followed a period of complete silence, after which a man cleared his throat and explained that, being Finnish, it was extremely difficult for them to speak in public; they preferred to come to the podium afterwards, one by one.

The Finns are a quiet people, and Helene Schjerfbeck — who has claims to be the greatest Finnish painter — is a quiet artist. But her pictures, which are on show at the Royal Academy, have qualities that mild-mannered and taciturn individuals sometimes possess: seriousness and intensity. When she does raise her voice, it’s all the more telling.

A good example comes early in the exhibition. ‘The Door’ (1884) was painted when she was 23 and at work in the artist’s colony of Pont-Aven in Brittany. It depicts a shadowy corner of a medieval building, perhaps the nearby chapel of Trémalo. One gothic arch can be seen, as well as a large area of blank wall and floor. The whole image is constructed of soft, subtly modulated blue-greys and dun browns — except for a tiny area surrounding a closed door, around which a thin strip of brilliant golden sunshine breaks through.

Although her idiom and subject matter changed drastically over the following 60-odd years, the little patch of bright colour singing out of a low-keyed picture continued to be a trademark. You find it in ‘Self Portrait with Red Spot’ (1944), a minute touch of scarlet that energises an otherwise entirely monochrome picture. So too did her preference for paint that, rather than being thick and shiny, was thin, matte and scraped down. She enthused about the ‘“dead” which yields such fabulous colour’.

‘The Door’, though executed in France, is a very Northern painting. It belongs with the empty interiors of the Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershoi (Schjerfbeck’s almost exact contemporary) in which the clear, cool light seems almost mystical. She has been billed as a female, Finnish Munch, but Hammershoi is a better match. Even so, there were many differences. Schjerfbeck may have been a quiet painter, but unlike Hammershoi, she is far from impersonal. On the contrary, a great deal of her painting — including an entire room of self-portraits in the exhibition — is about herself.

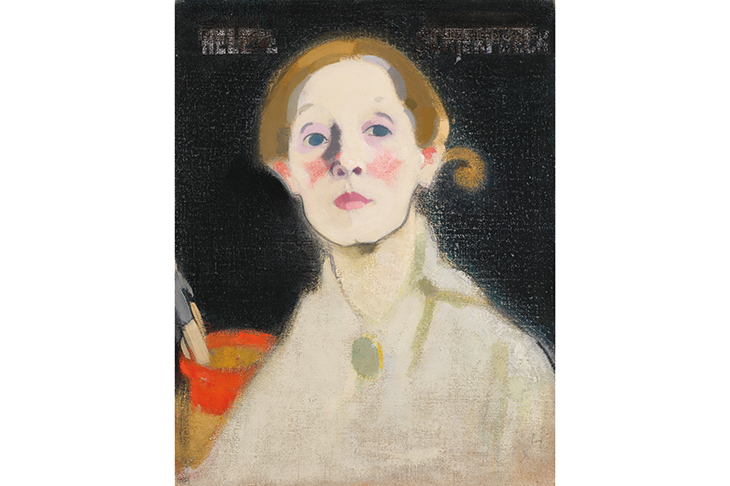

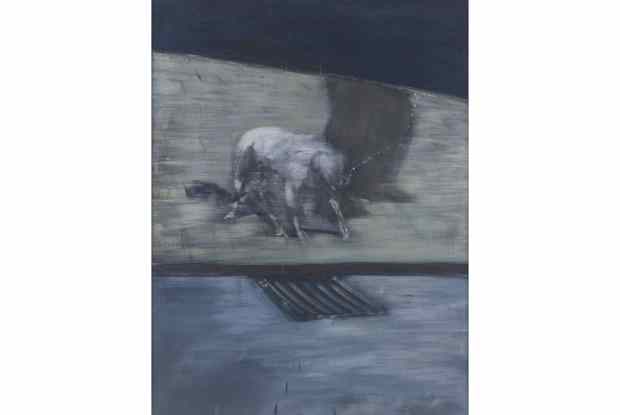

These pictures don’t have the fevered drama of Munch. Instead, there is a mild, unsentimental self-appraisal in her marvellous ‘Self-Portrait, Black Background’ (1915). It’s more akin to Cézanne’s visual self-examinations, in which — the poet Rilke famously noted — it was as if a dog had looked in a mirror and thought ‘there is another dog’.

The most extraordinary works in the RA show are the pictures which document her own personal disintegration in old age. This final sequence of paintings and drawings, done in a hospital in Sweden at the end of the second world war when Schjerfbeck was in her mid-eighties and dying of cancer, is one of the most unflinching treatments of the end of life in the whole of art (see p. 25). In its grim way, this last phase was a triumph: an old, lonely, mortally ill woman taking her own death as a subject, and dealing with it brilliantly. The near-abstract ‘Self-Portrait: Light and Shadows’ (1945), loosely, freely brushed entirely in shades of green, is one of the most radical things she did.

Since this exhibition opened the question has been asked: why haven’t we heard about Schjerfbeck before? One possible answer is, because she was a woman. It is quite true that many female artists have been unfairly sidelined, certainly in this country. But Schjerfbeck came from one of the most egalitarian societies in the world — Finnish women got the vote in 1906, the first in Europe to do so — and she won a considerable amount of recognition and support.

Although she was from an impoverished background — her father died from tuberculosis when she was a teenager — she won a travel grant from the Finnish senate that enabled her to travel to France, Britain (unexpectedly she worked for a while in St Ives) and Italy. It is true that after her return home, her work was criticised for being too French. But in her later decades, she achieved acclaim and sold many pictures.

It might be closer to the mark to say we haven’t heard about her because she was Scandinavian. Akseli Gallen-Kallela, her main rival for the title of leading Finnish artist, is not really a household name, even in the most artistic homes of Britain. Apart from Munch — who has always been a star — Nordic art is, if not exactly terra incognita, an area we are still exploring. Hammershoi, who had an exhibition at the RA a decade ago, was clearly an important artist. August Strindberg was more interesting as a painter than as a playwright.

Even in Scandinavia, Finland is the odd country out — it was still part of Russia until 1917. Nonetheless, as a country it certainly punched above its weight in architecture, producing two geniuses in the great modernist Alvar Aalto and Eliel Saarinen, the art nouveau master who designed, among other buildings, the magnificent Helsinki Central Station.

In painting it’s not so clear. Gallen-Kallela had his moments: there’s a wonderfully limpid landscape by him in the National Gallery, ‘Lake Keitele’ (1905). But he could also produce truly ghastly works in a pre-Tolkien, elves and goblins idiom. On this showing Schjerfbeck was a more considerable artist, though she too was uneven.

Much of her early work was visibly affected by Jules Bastien-Lepage, a painter of outstanding dullness who had a bad influence on a whole generation of European artists (so the Finnish critics were right to complain her work was too French). Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, she did a considerable number of pictures in a slightly cartoony, graphic idiom that — to my eye — just don’t work. But there are also enough understated masterpieces on show at the RA: the selfportraits, and also female figures of intense inwardness such as ‘The Seamstress’ (1905) and ‘Maria’ (1909), to suggest that from now on the name of Helene Schjerfbeck will be much more familiar.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in