He would want to be remembered as the debonair war hero who delivered Indian independence and became the royal family’s elder statesman. But something went wrong for Lord Louis Mountbatten. Andrew Roberts anticipated many modern historians when he called him ‘a mendacious, intellectually limited hustler’. Field Marshal Gerald Templer told him to his face he was so crooked that if he swallowed a nail, he’d shit a corkscrew.

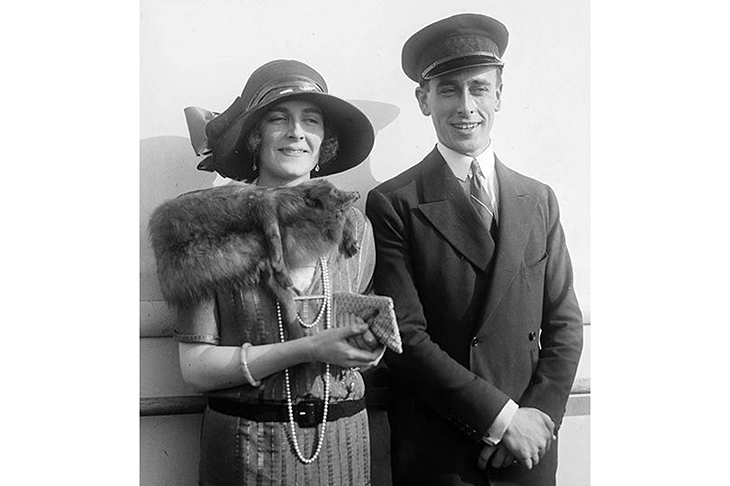

As reputations go, the turnaround has been extraordinary. Since many approaches to ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten’s life have been tried, and the personal archival material is carefully curated, Andrew Lownie has sought to throw new light through a joint biography of him and his much wealthier wife, Edwina Ashley, heiress to the fortunes of her maternal grandfather, the financier Sir Ernest Cassel, and to Broadlands, now the Mountbatten family seat. It is 40 years since Mountbatten’s horrific assassination in Ireland — the period he himself suggested, with typical conceit, would be required to assess his place in history.

Lownie has garnered many pre-publication column inches with his revelations that Mountbatten was almost certainly gay, or rather bisexual, though his financial returns will be less than Philip Ziegler’s, who was paid £350,000 by the Sunday Times for extracts from his official biography in 1985.

As throughout, Lownie weighs the evidence. Ziegler doubted his subject was gay. FBI intelligence suggested otherwise, but is unconvincing. On balance, Lownie’s accumulation of anecdotes from former associates recalling his trysts with men swings the vote. The subject is undoubtedly interesting, but does it matter? There is no evidence it affected his decision making.

Edwina was basically a selfish rich girl who, bored with her frequently absent husband, indulged in distant travel and brazen affairs, often with unlikely figures such as the conductor Malcolm Sargent and (it seems) the entertainer Paul Robeson, before finding her life’s calling as wartime chief of the St John’s Ambulance Service and, afterwards, in India as the viceroy’s wife. Her close relationship with Nehru raised eyebrows — a passionate, probably unconsummated, romance. But she died in 1960, aged 59; and although insights into an often hurtful but (eventually) accepting and loving relationship with Dickie can be gained from what intimate correspondence is available, he is really the focus of attention.

After taking us through Mountbatten’s German princely background and absorption into the British royal family, Lownie focuses on three main areas of his career. One is the second world war, where, after some buccaneering years at sea, he was (at Churchill’s insistence) brought into Whitehall as chief of combined operations. Almost his first task was the Dieppe raid, which proved a disaster, with heavy casualties, whether or not one believes it was a ruse for obtaining naval codes for Bletchley Park. Lownie wonders if Dickie was over-promoted and might even have prevented Dieppe altogether. But by late 1943 his decisive stewardship of combined ops had laid the groundwork for D-Day successes, and he was bound for India as supreme Allied commander South East Asia, with the task of turning the tide against the Japanese. Lownie’s verdict is that, in exceedingly difficult circumstances, he provided the energetic direction to give successful generals like Bill Slim their head.

In 1947 Dickie returned to India as viceroy at a critical time. Accompanied by Edwina, they proved a formidable couple, glad-handing communal leaders and princes, as the sub-continent careered towards independence. Lownie suggests the worsening situation left Mountbatten with little choice but to speed moves to Partition. His and Edwina’s personal relations with Nehru probably affected the outcome. But he delivered his wider brief and was able to return to his great love, the sea.

He couldn’t escape being recalled to the admiralty, and a succession of ever more senior posts, culminating in first sea lord, where Lownie gives credit to his efforts, as a Cambridge-educated royal with engineering patents to his name, in modernising Britain’s defences for the nuclear age.

After retiring as chief of the defence staff, Dickie courted further controversy through his supposed role in Cecil King’s 1968 ‘coup’ to oust prime minister Harold Wilson. He himself claimed no involvement, but Lownie suggests otherwise, which is odd since Dickie was politically progressive (willing to talk to nationalists in Burma, for example), even to the point of sympathising with Irish republicanism — which made his murder so mistaken.

The Mountbatten who emerges from this well-produced book is likeable. He’s an achiever, albeit a vain one, obsessed not just with his legacy but also with his position as an outsider in British society (his determination is Hanoverian, it is suggested). Like his sexuality, he is complex. In pulling together the available strands Lownie has achieved something special — a page-turner which is also a carefully researched work of history.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in