‘Why would anyone want to destroy something so beautiful, then stuff its poor lifeless body to keep as some kind of macabre trophy?’ In her first speech after moving into Downing Street, Carrie Symonds, the PM’s girlfriend, chose to attack trophy hunting. ‘A trophy is meant to be a prize, something you’re awarded if you’ve achieved something of merit that requires great skill and talent,’ she said. ‘Trophy hunting is not that — it is the opposite of that. It is cruel, it is sick, it is cowardly and I will never, ever understand the motivation to do it.’

Carrie is not alone. Lately, it feels as though there isn’t a TV celebrity who doesn’t feel outraged about shooting big game. Since its formation just over a year ago, the Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting has amassed a list of supporters that reads like the guest list for a BBC Christmas drinks do. Lorraine Kelly, Carol Vorderman, Nicky Campbell, Michael Palin and Ed Sheeran have all pledged their support. To be fair to Ed he has actually been to Africa, to Liberia, though the film he made there was considered by one African commentator to be ‘the most offensive and stereotypical fundraising video of the year’.

The trouble with all this righteous rage is that big game hunting, or trophy hunting, is far from a simple story. Hunting is an industry that, for instance, brings each of Namibia’s 82 community-owned game conservancies an average income of 100 million Namibian dollars a year (roughly £5.5 million). Furthermore, according to government figures, the sector has created 15,000 jobs including trackers and skilled taxidermists — there’s nothing nastier than a mouldy stuffed leopard. Even more interesting for Ed and Carrie, Namibia is a country where wildlife is booming, with the rhino population growing 6 per cent a year and elephant numbers doubling since 1995.

Earlier this year, just over the border, poor President Masisi of Botswana came in for a personal attack from Joanna Lumley who insisted that he keep in place the ban on hunting elephants. For a bit of context, Botswana has a stable population of 130,000 elephants. In other words, they’re doing just fine, thanks. It’s precisely because they were thriving that the decision was made to allow a number of elephants to be shot. This wasn’t just to bring in cash either — it followed a consultation that found rural livelihoods were being destroyed by more adventurous elephants trampling over farmland and coming into conflict with people. A team had been set up to usher them away, but inevitably the damage is done before they arrive.

Why should Lumley privilege the lives of elephants over people? And isn’t this white privilege at its worst? In some agrarian parts of Botswana almost 50 per cent of people live below the poverty line. It’s easy to see why, to ordinary Botswanans, Lumley lobbying the President to keep a hunting ban in place was classic western arrogance.

However much you love animals, it’s really worth trying to look at African conservation issues from an African point of view. Last year, Prince William came in for some stick after official footage was released showing him visiting conservation projects in Tanzania and protesting against poaching. The video featured just one black person, whose contribution was an adoring appraisal of William’s leadership skills. Mordecai Ogada, an ecologist who specialises in community-based conservation, suggested the film conveyed a damaging narrative: ‘The message that goes out is that African wildlife is in danger, and the source of the danger is black people.’

Dr Ogada has a point. And isn’t it a little rich of Prince William and his pals to decide to save African wildlife from poachers when British high society, in the last century, spent decades profiting from pillaging African ivory?

Dr Ogada also pointed out ‘the vilification of local people provides justification for human rights abuses, such as the indiscriminate shooting of poachers’. Tragically, fatal shoot-outs between landowners and poachers in Kenya are not uncommon. Ricky Gervais suggested on a 2015 radio programme that rather than hunt animals, why don’t we say ‘for $10,000 you can hunt a poacher’? Great idea Ricky: kill Africans for trying to monetise their own wildlife.

In the past few years, it has been reported that elephants and tigers in India, where hunting is illegal, kill one person a day. British tabloid readers will be familiar with stories about villagers brutally firebombing elephants that destroy their crops. Meanwhile, expensive military-style operations are regularly deployed by local authorities to track down man-eating tigers. It might be interesting to ask rural Indian communities whether they would welcome people who want to pay vast sums to cull problem creatures.

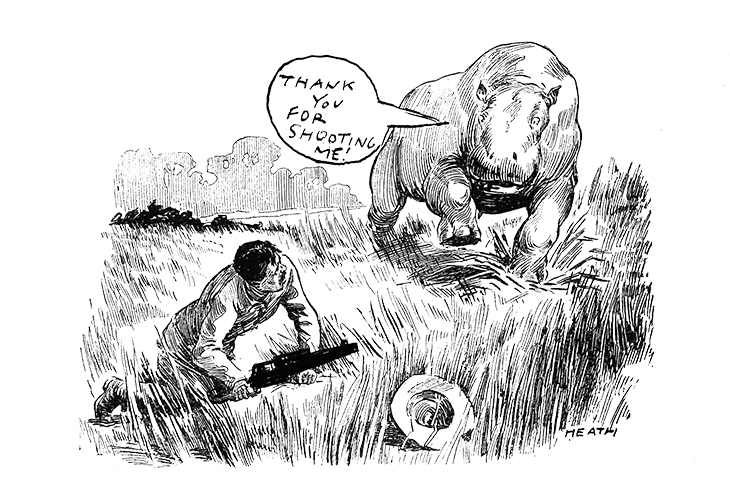

The irony of the trophy hunting ban — one that’s lost on its celebrity followers — is that the best way of preventing poaching is to sanction controlled trophy hunting. The mantra in Namibia when it comes to big game is that ‘if it pays it stays’. In other words, local communities look after wildlife because it is legal to sustainably monetise it. In the likes of Kenya, hunting is illegal and poaching is rife. There is bleak logic in the fact that if impoverished people can’t charge tourists to cull certain animals, they will simply slaughter them and make money from selling their body parts.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in