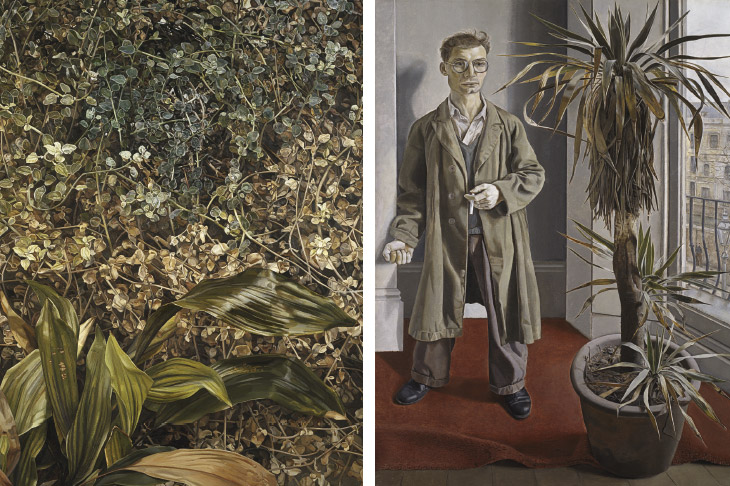

In early paintings such as ‘Man with a Thistle’ (1946), ‘Still-life with Green Lemon’ (1946) and ‘Self-portrait with Hyacinth Pot’ (1947–8) Lucian Freud portrayed himself alongside striking plant forms, giving equal weight to the vegetable and the human. Similarly, his first wife, Kitty, was depicted in portraits from the same period more or less obscured by a fig leaf held in front of her face, or apparently threatened by the leafy branch of a plant thrusting into the picture plane.

Throughout Freud’s career, people would continue (sometimes equally uneasily) to share space with plants, notably Harry Diamond confronting a yucca in ‘Interior at Paddington’ (1951) and the artist himself squeezed into the background by a pandanus in ‘Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening’ (1967–68). Freud would also make plants the principal subject of his paintings, from the marvellous array of succulents in ‘Cacti and Stuffed Bird’ (1943) to the beautifully spent buddleia flowers of ‘Garden from the Window’ (2002). Giovanni Aloi rightly suggests that this recurring feature of Freud’s work has been largely overlooked, and his book is an attempt to address this omission.

Given that Freud spent his formative years as a pupil of the artist-plantsman Cedric Morris, it is perhaps unsurprising that the vegetable world should figure so frequently in his work, though his approach to painting it was very different. Not for him the vibrant irises and poppies that Morris so loved; instead he tended to depict less obviously appealing species, often houseplants, without flowers and often well past their prime, detailing every discoloured or dead leaf. There is an obvious parallel here with the human bodies he painted, which generally did not conform to traditional notions of physical beauty, and Aloi suggests that Freud’s paintings of plants are indeed portraits, in which the subjects are ‘allowed to be what they are, irremediably engulfed in their laconic character and imperturbable demeanour’.

Much of what Aloi writes is illuminating, as when he notes that early in his career Freud chose ‘species whose morphology, in the structure of branches and the jaggedness of leaves, presented an affinity with his mark-making style’. Elsewhere, however, he can get rather muddled, seemingly torn between his insistence that Freud’s paintings ‘bypass’ the centuries-old tradition that ‘plants have expressed human qualities and values through symbolism’ and an academic urge to ‘read’ the paintings for meaning. For example, he explains how the huge zimmerlinde in ‘Large Interior, Paddington’ was propagated from the plant brought to England from Vienna by Sigmund Freud, and so the painter’s seven-year-old daughter, who lies under it, ‘rests in the shadow of a patriarchal heritage she cannot yet grasp but that will be very meaningful for her future’.

The principal attraction of the book is its plates, which are particularly well chosen from the early years, and one wishes Aloi’s annotations of them were less sporadic. More useful than a rather dutiful essay on the ‘History of Plants in Art’ would have been a systematic commentary on the individual paintings and the plants they depict. Even so, Aloi’s focus on plants makes one look again at familiar paintings and provides the opportunity to view others, many of them from private collections, that are equally extraordinary but comparatively little known.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in