In the autumn of 1987, after London had been hit by a fierce storm, Simon Jenkins wandered through Bloomsbury and noticed that workers clearing away the fallen plane trees were finding it hard to cut through the branches. When he looked closely, he saw this was because their chainsaws kept snapping against embedded fragments of wartime shrapnel. It’s a nice detail, and there are many in Jenkins’s new book, though he spoils this one by adding that ‘London never lets us forget its history’.

On any other day, surely, this legacy of conflict would have eluded his attention rather than imposing itself upon it. One of London’s features is its genius for self-renewal — after the Great Fire, for instance, as well as after the Blitz. In the process, a huge amount is swept into the dustbin of oblivion. Isn’t the real point of a book of this kind that it is all too easy to be ignorant of the city’s past? That, for example, London wants us to forget it was once not a beacon of sophistication, turning its back on the Thames, but the world’s largest port and a grimy centre of manufacturing?

For Jenkins, though, the surpassing virtue is vigorous concision. Not for him the exploratory breadth of other recent histories — Peter Ackroyd’s strange circumambulatory performance, Stephen Inwood’s mighty feat of myth-busting and Jerry White’s unflinching portraits of urban monstrosity. By page 43, Jenkins has already got as far as Henry VIII. As he zips along, there are toothsome nuggets: Dick Whittington’s public latrine in Cheapside had 128 seats; and John Evelyn, who felt that London’s ‘tiresome’ trades should be shunted east to make way for fragrant groves, was keen to spare residents the need to inhale ‘fuliginous’ vapours. But the city’s rich literary culture is treated cursorily: there’s nothing from George Gissing, Thomas De Quincey or Virginia Woolf, and all Jenkins has to say about John Milton is that he was a parliamentarian.

The emphasis is on London’s appearance, which he considers ‘more variegated and visually anarchic than any comparable city’. As befits someone who has chaired the National Trust and been a trustee of the Architecture Foundation, he is interested not only in the aesthetics of the built environment, but also in the tangled politics of what gets constructed and what does not. Inasmuch as he fleshes out characters, they’re technocratic types, such as the town-planner Patrick Abercombie, the great enemy of suburban sprawl, and Charles Tyson Yerkes, a shady American who was instrumental in the development of the Underground.

Jenkins grew up on the fringe of Camden Town — Withnail and I country — and the book is best when most strongly coloured by his experience. Seeking to evoke the atmosphere of 14th-century London, he pictures ‘the squalor of 1970s Calcutta, transplanted into the physical streets of modern York’. He writes pungently about Richard Seifert, the designer of Centre Point and several other slab-like edifices, who ‘murdered London’s streetscape’, and there are quick, sharp sketches of the Napoleonic Tony Blair, and of Ken Livingstone — ‘a refreshing as well as an alarming presence on the London stage’. He can remember sitting on his father’s shoulders as the Olympic torch was lit in 1948 at Wembley and, many years later, being buttonholed at a seminar in Bethnal Green by smartly dressed drug dealers, who felt he was planning to run them out of business. He also recalls that when his parents’ old flat went on the market in 2001, the estate agent insisted that its appeal was not its being in the Barbican, but its proximity to the night-time buzz of Hoxton.

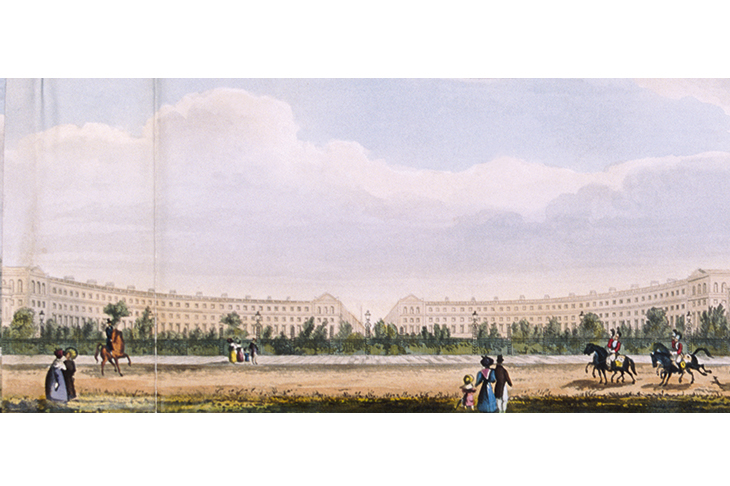

These personal snippets have charm, and A Short History of London is attractively packaged. The front endpapers reproduce a bird’s-eye view of the city from around 1550, and there’s a generous selection of plates. Yet the lack of endnotes is frustrating. It leaves one uncertain about the provenance of Jenkins’s information, some of which is wayward. He quotes Queen Elizabeth I referring to Thomas Gresham as a ‘necessary evil’, but the phrase appears to come from the jacket copy for a modern biography of Gresham. Soho Square is not, as Jenkins asserts, the only London square that truly has that shape. Jane Austen does not record spending five pounds in a day while shopping in Covent Garden. He mangles the context of Dr Johnson’s most famous quotation about London and in the next paragraph does the same to a line of Voltaire’s. Altogether more fantastically, he claims that the city’s Boris Bikes lose £160 million a year.

Mistakes such as these perhaps do no more than nibble at the authority of Jenkins’s account, which is always lucid. Yet he has a tendency to cramp vividness with didacticism — to sound less like a historian, gleaning evidence from primary sources, than a political columnist hooked on epigram.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in