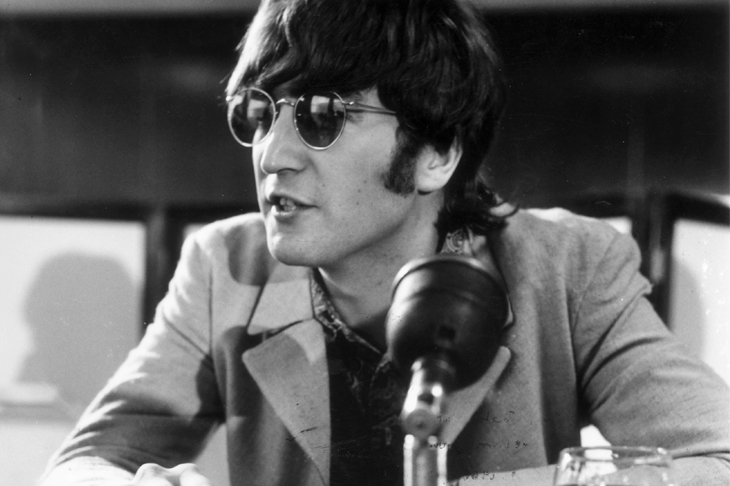

For several years in the 1950s Peter Jones shared a desk with John Lennon at Quarry Bank High School for Boys in Liverpool. The two would sometimes skive off from school together to buy fish and chips at their favourite chippy—in Penny Lane. But after high school their thinking, and their lives, headed in polar opposite directions. John Lennon told us to:

Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky…

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion, too

But Peter Jones decided there was something worth living and dying for and became a Christian theologian. He headed to America to study at, and graduate from, Harvard. Then he took his wife and young family to the south of France to teach New Testament Greek at a college in Provence for nearly twenty years. He returned to the states to become a professor at Westminster Seminary. Both Lennon and Jones had a ‘ticket to ride’, but in opposite directions.

When I met him recently during his speaking tour of Australia, I found no trace of Liverpudlian in his voice. All those years of working and living with Americans (his wife is American) have left him with an accent that is closer to Philadelphia than mid-Atlantic. For the past twenty years Professor Jones has been investigating the decline of Western civilisation and his conclusions may surprise some. Far from seeing the spirit of the West being killed by the triumph of secular humanism, Jones insists we live in a post-secular age—and it’s this post-secularism that is shaking the foundations of Western civilisation.

Far from abandoning all spirituality, he argues, Westerners in huge numbers have embraced a new spirituality—often identified with the expression ‘I’m spiritual but not religious’. (How often have you heard that?). But there is, he insists, nothing truly new about the current spiritually; in reality it is nothing more than ancient paganism in a new, respectable and fashionable form.

Much of the Western world, built on Judaeo-Christian foundations, is now losing its traditions and its heritage to the vague pantheism and warm, fuzzy feelings of this new paganism.

It finds expression in many forms: in the New Age spirituality of hippiedom; in the ‘perennial philosophy’ of Joseph Campbell; in the nature worship of the climate change alarmists; in revived interest in shamanism and indigenous practices; in the popularity of Indian gurus (here John Lennon and his fellow Beatles led the way); in the rise of yoga and meditation (‘mindfulness’) in the West; and the influence of Carl Jung (which Jones sees soaking through much of modern thought). Jones gives this new spirituality the name of ‘Oneism’ since what unifies all these many and varied threads (and connects them to Marxism) is the denial of transcendence: there is nothing above and beyond the mundane—this world, it claims, is all there is.

Forget transcendence, natural law, eternal truth or stability. Everything is part of the One fluid reality. Distinctions are illusions. Reality is One. The technical name for this sort of thinking is ‘monism’: the assumption that ultimately everything consists of a single principle or kind. True and false, good and evil, ugly and beautiful, are all equally valid expressions of one underlying amorphous, impersonal reality.

The whole point of what Professor Jones calls ‘Oneism’ is to eliminate differences. Hence, gender becomes fluid and all genders melt into one; humanity ceases to be distinct from the rest of the animal world, with humans being of no more inherent value than chickens and of less value than endangered species. In the world of ‘Oneism’ there can be no real distinction between right and wrong; universities become places of conformity and propaganda rather than open debate searching for truth; and human flourishing is undermined by attacks on families, churches, charities, clubs and anything else that encourages the harmonising of differences (rather than the elimination of differences).

If the idea of a pervasive ‘Oneist’ worldview capturing our civilisation sounds extreme, just stop and think how much this is found in political correctness. This is the worldview unifying the Extinction Rebellion activists gluing themselves to the road and the directors of corporations forcing identity politics and political correctness on their companies.

By losing transcendence, Oneists (whether they consciously realise it or not) worship the world while acknowledging no transcendent truth, or transcendent morality, or transcendent beauty.

The alternative, embodied in the great traditions of Western culture, Jones labels ‘Twoism’. There are, he insists, only two major worldviews striving for dominance in our Western world—the Oneism that abandons all transcendence and permanence, and the Twoism that has built our civilisation from the Greeks, Hebrews and Romans to the present day. Twoism has been our foundation for two thousand years or more, and Oneism is ‘the other worldview’.

The ‘Oneists’ he says worship and serve creation not the creator, eliminating all distinctions, treating everything as divine, and finding spirituality within themselves. ‘Twoists’, on the other hand, follow the path that produced Western civilisation: acknowledging that there is a Mind behind the universe—the source of truth, beauty, meaning and morality. Twoism is the worldview that gave us Shakespeare, Bach and Rembrandt; that gave us democracy, charity and respect for the individual.

Mind you, one short review cannot do justice to the wealth of scholarship Professor Jones packs into his closely argued book. However, what it’s not possible to deny is that there is a zeitgeist—there is a spirit of our times. Just what that spirit is, and where it is leading us, is unpacked in impressive detail by Professor Jones.

I must admit I found much of this book, which was originally published in 2015, profoundly depressing as Jones piles up one piece of evidence on another to show that the dark cloud over our culture is gathering strength.

Until, that is, I came to the last two chapters. There Jones turns his spotlight onto observable, rational reality—onto the real difference between The Truth and The Lie. As Jesus said: ‘You shall know the truth and the truth will set you free.’

But is it really as straight forward as that? Are political ideologies and traditions only the topsoil that lies on the bedrock of just two dominant worldviews? That’s certainly the claim Professor Jones makes. To test his claim you need to read his book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in