Eating makes us anxious. This is a feature of contemporary life: a huge amount of attention is devoted to how much we eat, when we eat it, where it comes from, to toxic foods, organic and inorganic ones, environmentally damaging groceries, those that tot up too much mileage or cause damage to the rainforest.

Some of these worries are relatively novel, but preoccupation with the nourishment we consume is not. A remarkable and imaginative exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Feast & Fast: The Art of Food in Europe, 1500–1800, documents just how obsessed our ancestors were with every aspect of their meals.

At its heart are a series of recreations by Ivan Day, a specialist on the subject of what can only be described as edible art. The first you encounter is a Jacobean banquet, c.1610, in which not only are the comestibles extremely sweet, even the crockery is made of moulded sugar. Titbits designed to appeal to sweet Stuart teeth are displayed in an elegant bowl held up by the tails of miniature dolphins — these last derived from designs by Giulio Romano.

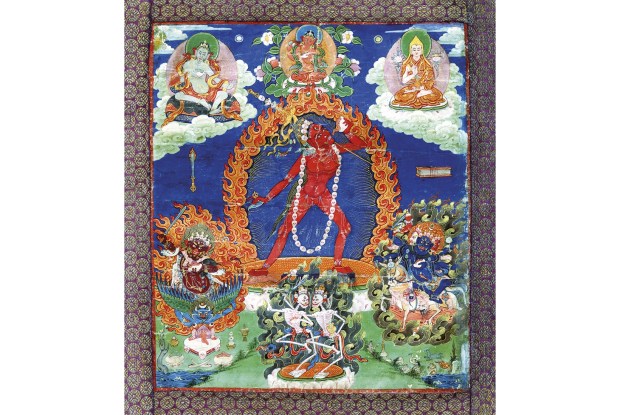

So there you have it: art you could crunch and suck like a stick of rock (though probably at significant dental risk). There were many such aesthetic lollipops on the tables of the wealthy of Renaissance Europe. In 17th-century Rome, cardinals were known to place martyred sugar-saints by notable sculptors in the centre of the spread.

Understandably, such edible statuary did not survive longer than the meals it adorned, so it is fascinating to see these re-created examples. My favourite, though, was more sweetshop neoclassical than baroque: a recreation of an 18th-century London confectioner’s window display, featuring a couple of iced cakes exactly like Adam ceilings (or, an intriguing thought, perhaps 18th-century plasterwork copied these elaborately decorated bakery products). There is even sugar architecture on show, including a miniature rococo palace and formal garden as illustrated in a Parisian pastry cook’s manual of 1768.

The other exhibits naturally consist of the kind of uneatable stuff that usually ends up in museums — ceramics, prints, paintings, and ornate silver plate. There is a spectacular array of the last once owned by Matthew Parker, an Elizabethan Archbishop of Canterbury, including tankards, posset cups and salt cellars. The point was not so much to eat or drink from this stuff as to impress the guests.

The same is true of the mounds of costly foodstuffs you see in still-life painting, and which were served up in reality. At his coronation banquet in 1685 James II and his consort Maria di Modena sat down alone, in Westminster Hall, to a meal of 170 dishes (which definitely qualifies for the description ‘conspicuous consumption’).

An unusual example of fruit portraiture commemorates the first pineapple cultivated in England, which ripened in Sir Matthew Decker’s Surrey garden. These fruits were then an expensive treat: raising this one in 1720 cost the equivalent of £9,000 in today’s money. The craze for this strange-looking and costly luxury led to pineapple-mania — a gastronomic equivalent to the earlier outbreak of Tulipmania in the Netherlands.

The price of pineapples later came down, of course; so did that of sugar, once a great treat, as a result of the plantations of the Caribbean. One of the themes of the exhibition is how early globalisation changed and expanded the European diet, but sometimes at a terrible cost — in the latter case to the African slaves who cultivated that sugar cane.

Over the years we have become more queasy than our Elizabethan or Georgian ancestors about the sources of our diet. It’s hard to imagine those paintings of blood-spattered mounds of slaughtered game —Frans Snyders was among the masters who specialised in them — ever coming back into fashion. Even in the past, however, there was some disquiet about culinary cruelty to animals.

A drawing by Jacob III de Gheyn shows a duck, plucked alive and hung up by its neck and one leg. The poor creature looks like St Sebastian on an altarpiece: it’s hard not to see this as a piece of protest art. A 16th-century print shows some hares getting their revenge: they’ve captured the huntsman and are roasting him on a spit.

Eating made our forebears uneasy, if not in quite the same ways as concern the early 21st century. They were aware that gluttony was a sin, as was the pride involved in boastful displays of silver plate, tropical fruit and sugar sculpture. So they alternated — just as many of us do today — between bingeing (if they could afford it) and cutting right down. Although the latter regime is harder to exhibit than excess, it was just as prominent a part of life. Neatly, and deliberately, Feast & Fast will run through Christmas until the end of Lent.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in