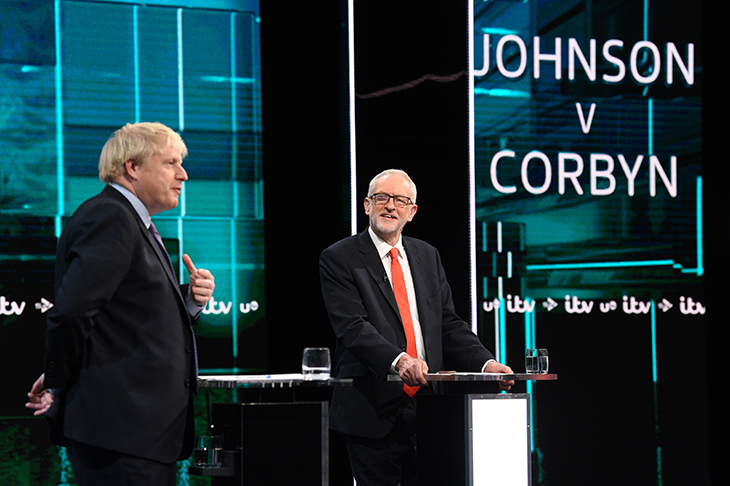

There is something deeply unsatisfying about the debates featuring party leaders. The questions put to them, whether by an audience or presenter, are the routine ones that they face every day and therefore draw routine responses. What they never get is an interrogation. Enter Socrates, licking his lips.

He once described how a friend of his had asked the oracle at Delphi whether there was anyone wiser than he. The Pythia answered ‘No’. Baffled by this, Socrates set about to prove her wrong. He failed. After interrogating a wide range of people he concluded that he was wiser, but only in this respect, that he knew he was ignorant, whereas they did not.

How, then, to put his ignorance to good use? By analogy with a midwife: unable to deliver wisdom himself, he might become a means of delivering it in others. So his interrogations began by asking his interlocutor — let us call him Pspon — a simple question, and then probing the answer with further questions until it became clear that his answer would not do. In the light of this criticism Pspon would supply a second, modified answer, which Socrates would again dismantle, and so on. By the end of the process, though no answer had been produced, at least Pspon had been made aware of the issues at stake and his own ignorance — the beginning of Socratic wisdom. The point here is that Socrates was not just trying to win an argument by tough questions or searching for contradictions (the great strength of Andrew Neil) but to educate Pspon into seeing for himself that he did not know what he was talking about.

This style of interrogation will, of course, never happen. Far too challenging for viewers, let alone your average TV presenter, for whom the ability just to ask a question rates as a feat of incontestable genius. Two and half millennia ago, however, the ancient Greek man in the street lapped it up. But then, every week he was in the assembly, listening to political arguments on all sides, weighing them, arguing and voting on them. It was called democracy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in