As late as the end of the 18th century, only a handful of Europeans had ever seen the legendary Mughal capital of Delhi, which, within living memory, had been the largest, richest and most spectacularly beautiful city on earth, twice the size of London and Paris combined. But after a century of anarchy, Delhi was not what it once was. By 1805, it lay half-ruined and sparsely populated, ruled by a blind Emperor from a crumbling palace.

Delhi’s ruins bewitched the young artist James Baillie Fraser when he arrived in the 1810s from Calcutta. Fraser was already planning two series of aquatints, one on Calcutta, the other of the Himalayas. What he saw in Delhi inspired him to dream of producing a third volume, this time of views of the old Mughal capital: ‘I have been of late literally stunned by views of mosques and tombs and ruins, wrecks of Delhi’s former greatness,’ he wrote. ‘In comparison all our Gothic castles and Roman fortifications sink into nothing…’

Fraser had trained as an artist under George Chinnery in Calcutta and had come across the new fashion of commissioning talented Mughal artists to paint detailed records for their new East India Company patrons. During his stay in Delhi Fraser commissioned a number of leading artists from the Mughal court to paint Delhi’s figures and monuments, as aide-memoires for his projected aquatint series. The completed volume of paintings, now known as the Fraser Album, are today regarded as some of the greatest of all Indian artworks, with single pages changing hands for around a quarter of a million pounds. But there were many other patrons, and many other albums, in which you could find pictures of birds, plants, bats, monkeys, mice, fish and pitch-black sloth bears.

In a major new exhibition at the Wallace Collection I showcase 100 masterpieces from this diverse set of artworks that came to be called the ‘Company School paintings’, most of which have never been seen before. In particular, Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company brings together the finest pages of the Fraser Album for the first time since the album was broken up and sold in the 1980s.

The exhibition celebrates some of the master Indian artists working between the 1770s and 1840s: Shaikh Zain ud-Din (see p71), Bhawani Das, Vishnupersaud, Manu Lall, Sita Ram, to name a few. Their paintings, often of astonishing brilliance, and possessing a startlingly hybrid originality, represent the last phase of Indian artistic genius before the onset of the twin assaults — photography and the influence of western colonial art schools — ended an indigenous tradition of painting going back 2,000 years.

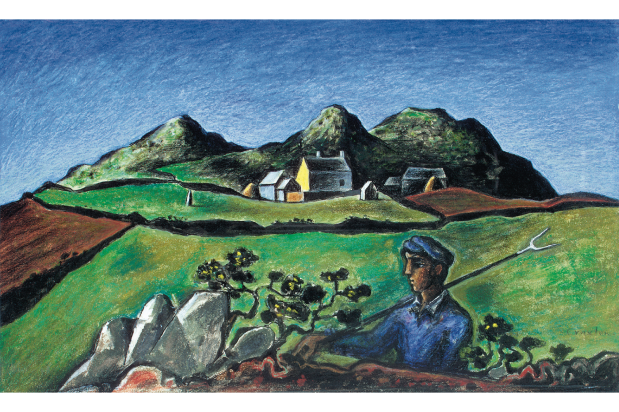

‘Arum tortuosum (now Arisaema tortuosum, family Araceae)’, c.1821, by Vishnupersaud

The artists who produced these works were drawn from a wide variety of Indian artistic traditions — Mughal, Maratha, Tamil and Telugu — and an equally wide range of castes and communities ranging from titled imperial office holders like the grand Mughal artist Ghulam Ali Khan, whose family worked on the Fraser Album, to much more humble artists who described themselves as moochies and who seem originally to have been leather workers and so at the very bottom of the Indian social scale. These artists were commissioned by an equally diverse cross-section of East India Company officials and their wives. What they all had in common was a scholarly interest in India’s rich culture, history, architecture, society and biodiversity.

Astonishingly, there has never been a museum show of Company-commissioned Indian art in this country, despite Britain possessing unrivalled masterpieces in both museums and private collections. The reason for this is not aesthetic so much as political. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the art of Empire came to be regarded in Britain with a profound distaste. Most paintings with imperial themes were simply taken off the walls and put into storage. A few were packed off to languish in the provinces. ‘The Remnants of an Army’, Lady Butler’s famous image of Dr Brydon — the sole survivor of the disastrous 1842 retreat from Kabul — one of the most iconic paintings of the Empire, was quietly removed from the walls and sent to languish in a regimental museum in Somerset. Today it is almost impossible to find any major gallery within Britain that still puts on show a significant collection of art connected in any way with the former British Empire. Disowned by subsequent history, the art commissioned by the Company has effectively been orphaned and ignored.

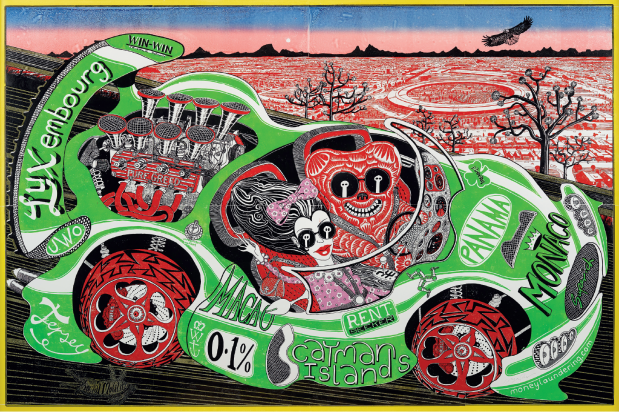

‘A Great Indian Fruit Bat’ by Bhawani Das

Now, perhaps for the first time, the works are beginning to get the attention they deserve. This is especially so of the reassembled pages of the Fraser Album, perhaps the principal treasures of the show. The images provide a panorama of the transition period between Mughal and Company rule, when the cultural and artistic life of the Mughal capital was intact but political power beginning to ebb from the Mughals to the British. We see Mughal dancing girls and Hindu holy men, Sikh princes, Afghan horse dealers and local Nawabs riding tigers. Among the finest images on show are depictions of village recruits who joined the newly founded regiment of Skinner’s Horse, founded by James Skinner, a half-Scottish, half-Rajput mercenary cavalry leader who in turn recruited warlike villagers from the area around Delhi.

We even get a tantalising glimpse of family life. The village of Rania, now in Haryana, was home to Amiban, main mistress to William Fraser, James’s brother, and his two Anglo-Indian sons and daughter. William’s connection to the village means that there is an intimacy here quite remote from the usual colonial commissions, and the figures, who are superbly painted with a realist flourish by the Fraser Album’s master portraitist, were all intimately known to William, and formed part of the inner circle of family, lovers and friends. As he himself wrote in the Album, before sending it down to Calcutta to his brother James, its images recorded ‘recollections that never can leave my heart’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in