Next week, voters will decide the future of the government, of Brexit, and perhaps of the Union. Jeremy Corbyn has been admirably clear on what he offers: a radical experiment in far-left economics, going after the wealthy to fund the biggest expansion of government ever attempted in this country. Boris Johnson proposes to complete Brexit and restore much-needed stability to government. But given that about half of voters still oppose Brexit, the race is close.

Corbyn offers a new referendum on Brexit. It is easy to snigger at his declaration that he would be neutral during this campaign. But his pledge to be an ‘honest broker’ conceals the deceit that his referendum represents. Voters wouldn’t be asked to choose between the current Brexit deal and Remain, but between Remain and a new deal, yet to be negotiated, which would almost certainly be Remain in all but name. It would be a mockery of a choice and would ensure that the second referendum would inflict even more damage on our democratic fabric than the first. Additionally, after being promised a ‘once in a generation’ referendum in 2014, Scots would likely be subjected to another independence campaign — as the price for the SNP propping up a minority Labour government.

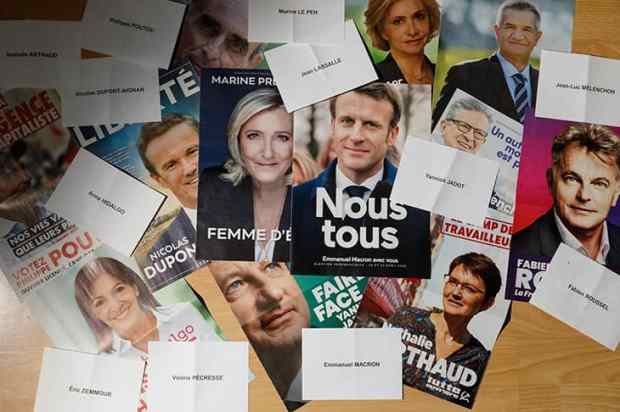

Yet these referendums would be minor headaches compared with the economic chaos. Under a Corbyn government we can expect a flight of capital caused by an attempt to bring back mass collective ownership and confiscation of private property in the form of nationalising 10 per cent of every company. If this comes about, it will be because not enough people took Labour seriously: they did not believe it would happen. The shocks of recent elections — the election of Donald Trump, the triumph of Brexit and populist victories across Europe — have shown that the unthinkable is happening on a fairly regular basis. Who is bold enough to argue that this pattern of a big election surprise is not going to be repeated this time?

Even if the Tories do get over the line on 12 December, they still have much to think about. Corbyn has managed to sell socialism to a new audience of young voters. Age, not social class, has become the main political divide in Britain. There are socioeconomic factors in his favour, most notably falling rates of home-ownership — a whole generation no longer has the stake in capitalism that their parents did. Corbyn’s spending plans, reckless as they are, do not seem so frightening to a generation which has never known interest rates much above zero.

Even so, Corbyn has only got as far as he has done because he is a far better strategist than he is given credit for. He has been careful to phrase proposed rises in personal taxes in a way that does not sound extreme — his top rate of income tax, at 50 per cent, would be no higher than that which George Osborne imposed on taxpayers for several years, although it would kick in at a lower rate. (It is, though, hard to believe that spending the equivalent to another NHS every year could be funded simply by taxes on the richest 5 per cent and big business.)

The Tory campaign this time has been haunted by the spectre of 2017. One result of this has been a cautious manifesto, designed to avoid pratfalls rather than make an argument. There are hints in the document of the Britain that Boris Johnson wants to see, but not a full-blown prospectus. The Prime Minister has been cautious to the point of timidity, which does not suit him.

Tories have become too reliant on negative campaigning, and struggle to explain that their policies are delivering progressive reforms that always evaded Labour. From the record amount of tax collected from the richest to the highest employment rate ever: there is much to boast about. The international league tables this week showed English schools soaring – and doing so while money was tight. This is just the latest proof that schools are improved by reform – entrusting and empowering teachers – not stuffing more cash into a failed system.

Those who claimed that austerity would cripple Britain are today struggling to explain why employment is at a record high, household disposable income is at a record high and income inequality near a 30-year low. The usual trick is to point to food bank usage, without admitting that the Tories increased this vastly by integrating food banks into the welfare state. The IFS recently found that ‘severe forms of material deprivation have fallen by a fifth’ since David Cameron first came to power. This is the real story of the decade, which food bank statistics are used to conceal.

A sense of perspective is also settling in over Brexit. Again, it’s possible to mislead with statistics and claim that some economic model or another suggests people will become ‘poorer’. None does. Every model predicts that Britain will become richer: the only question is whether it will be (for example) 15 per cent or 20 per cent richer over ten years – and given the error margin over such timeframes, the forecasts are usually meaningless. Smoke and mirrors can always be used to hide success. The trick for the Tories is to blow the smoke away, and point to that success.

In the final few days of the campaign, three messages are needed. First, that to vote Labour means another year wasted, by having a second Brexit referendum and a second Scottish independence vote. Second, far-left economics cause damage: investors’ confidence can shatter, forcing up interest rates and leading to a budgetary crisis requiring emergency spending cuts. And finally, Boris Johnson should be clearer about his vision for Britain, about how he intends to boost the economy outside London and the south.

The sheer pace of political drama this year has left the country exasperated and exhausted. Many Remainers and Labour supporters will be tempted to abstain, given the prospect of a Corbyn government. But Ian Austin, the Dudley North MP who quit Labour in disgust, has put it well: democratic elections mean picking sides. And by the end of next week, either Jeremy Corbyn or Boris Johnson will be in No. 10. In this regard, the British system offers a crude, binary choice. Some may wish it were another choice. But it’s the only one on offer.

It will be tempting for many to abstain, to give next week’s election a miss and hope that this muddle somehow resolves itself. But that would be a grave misjudgment. The stakes are as high as in any election in living memory. Never in our country’s modern history has it been more important to vote — and vote Conservative.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in