Dora Maar first attracted the attention of Pablo Picasso while playing a rather dangerous game at the celebrated left-bank café Les Deux Magots. She ‘kept driving a small pointed penknife between her fingers into the wood of the table’. From time to time she missed, and a drop of blood appeared on her gloves. This alarming form of digital Russian roulette was the basis for an early work by the performance artist Marina Abramovic, who will be featured at a major show at the Royal Academy next autumn.

There is nothing so arresting in the large exhibition devoted to Maar’s work at Tate Modern as the images of the artist herself, and not only those by Picasso. There are some individuals who have an impact on the arts through sheer force of personality. Photographic portraits suggest she had remarkable beauty combined with brooding force.

Born Henriette Theodora Markovitch (1907–97) to a Croatian father and French mother, she had worked in any number of idioms and media both before and after her years with Picasso in the late 1930s and early 1940s. On show at Tate Modern are surrealist photomontages — a sky filled with eyes, a human hand emerging from a spiral seashell.

Better, to my mind, was the street photography she practised for a period in the mid 1930s. Some of her shots of the poor in London and Paris around 1934 bring the work of Cartier-Bresson to mind, and stand up to the comparison too. Overall, though, these galleries are subject to the usual problem of large displays of small photographs: the exhibits look better in the catalogue than they do on the wall.

Maar’s paintings of the later 1930s and 1940s were heavily influenced, unsurprisingly, by Picasso. One of the most interesting sections of the show — her photographs of the unfinished ‘Guernica’ in his studio — relates as much to him as to her.

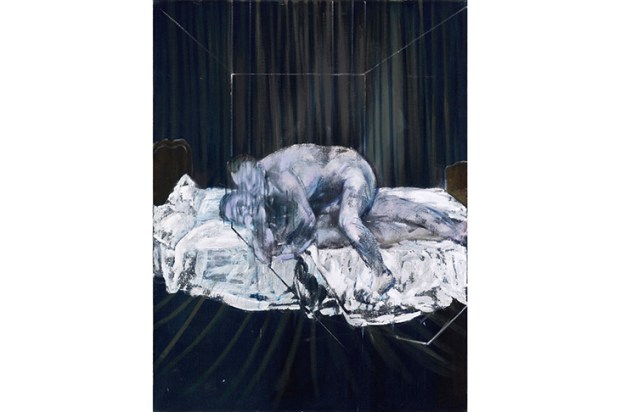

It is interesting to learn that two aspects of that masterpiece seemed to have been lifted from Maar. The black and white palette was perhaps suggested by her photography; and the bare dangling light bulb — which hung in her studio — had appeared before in one of Maar’s paintings (this motif was later recycled by Francis Bacon). But then we knew already that great artists don’t borrow, they steal. One leaves the show reflecting that while Maar deserved a reassessment, to fill this amount of space in a major museum requires a huge talent. She clearly didn’t have that.

The Tate collection itself would be a good deal richer in masterpieces if it had managed to acquire Peggy Guggenheim’s collection, as at one point seemed possible. Instead, of course, it stayed in her unfinished palazzo in Venice. Earlier, however, she had had a close connection with London, where in 1938–9 she put on a series of exhibitions in a pioneering gallery devoted to modernist art, Guggenheim Jeune.

This half-forgotten episode is the theme of an intriguing little show at the Ordovas Gallery, Savile Row. This is the reverse of the Dora Maar retrospective: an exhibition one can’t help wishing were bigger. During the short period for which it operated, the London Guggenheim gallery presented an extraordinary array of artists, including Kandinsky, Jean Cocteau, and a number of local figures — such as John Tunnard and Stanley Hayter — deserving of reappraisal.

Understandably, given limited space, Ordovas have concentrated on two: the surrealist painter Yves Tanguy and Jean (or Hans) Arp, an Alsatian exponent of a sort of fluidly organic abstraction. The works by the latter — sculptures and pictures suggesting primitive single-celled creatures, while not depicting any specific species — are well worth a long look. But a reconstruction of Peggy Guggenheim’s whole programme would be a fascinating snapshot of a moment in the history of taste.

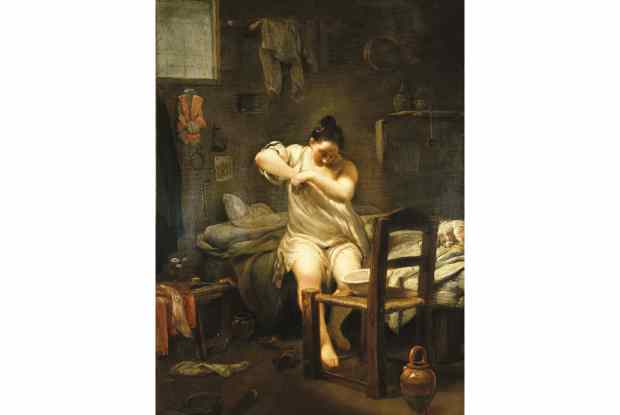

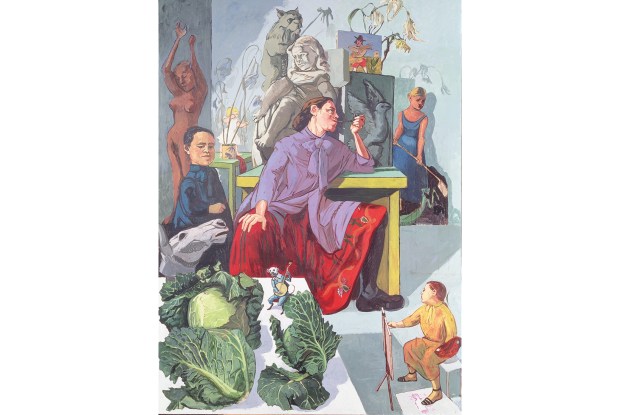

Celia Paul is a living painter who is just, at the age of 60, beginning to get the attention she deserves. Her exhibition at Victoria Miro (16 Wharf Road, N1) consists of pictures of people — mainly female members of her family including her mother, sisters and Paul herself — and landscapes. She is known for her relationship with Lucian Freud, and posed for a number of important works by him. There is a touching little posthumous painting of the two of them in the exhibition. There is little connection, however, between her work and his.

There is a feeling in the remarkable ‘My Mother and God’ (2019), and some more recent portraits, that the subject is immersed in a void, a dark vat of space. In contrast, Paul’s seascapes — especially the ones done this year at Santa Monica — have an almost mystical feeling, the rippling waters extending into infinity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in