Travel writing is ‘the red light district of literature’, as Colin Thubron aptly put it, a space where anything goes. Like punters to the other red light districts, we tend to stick to what we know we like, to our own kind. We travel vicariously with voices that are familiar, or at least intelligible, whose behaviour we can understand, whose narrators we believe we can know. That belief allows them to take us to places we have never seen. How, then, can we follow a foreign author’s account of travelling to, or living in, a place we don’t know? I thought this would be an interesting problem while reading Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara.

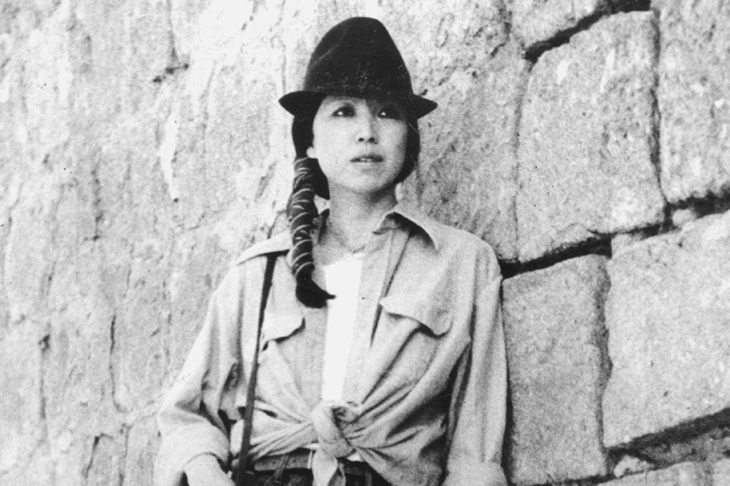

Sanmao is not the author’s real name. Born Chen Maoping in China in 1943, she was brought up in Taiwan and educated there, and in Madrid and Germany. In the early 1970s, she married a Spaniard. He loved water, but she dreamed of the desert. Her background is significant because the stories she tells are as much about herself as about the place she found herself living in.

That place was the Spanish Sahara, now the Western Sahara, disputed between Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Had this book been written by a British or American writer, we might have expected tales of long camel journeys, insights into the indigenous Sahrawis and perhaps their struggle against the occupying Spanish, who finally abandoned the colony in 1976, the year this book was first published in Taiwan. Instead, we are entertained with Sanmao’s tales of marrying José, a good man but not the love of her life (there had been a German fiancé, who had died before their wedding); of building a home on the unglamorous side of the unglamorous city of El Aaiún (Laayoune) and of engaging with the impoverished Sahrawis in her neighbourhood and with the wider community.

These and other winding stories in the collection are filtered through Sanmao’s very individual vision. ‘I’m Chinese,’ she wrote to the editor of the Taiwanese magazine that first began publishing her stories; ‘I have a Chinese heart; this part can never change.’ The stories appealed when they first appeared — and they have sold more than ten million copies in China and Taiwan — precisely because she was so Chinese and was living in a faraway place. They engaged their readers’ sense of escapism, their longing for freedom and for the exotic, of which there is plenty, from women in hammams — and having enemas on a beach — to a neighbour’s goats crashing through the ceiling. There is also the horrific — including mute slaves and child brides. But reading their stories on this rain-swept island, far from either Taiwan or the Sahara, what seduced me most was the combination of Sanmao’s voice and her indomitable spirit — a spirit that manages to reconcile her dream to be ‘the first female explorer to cross the Sahara’ with the reality of the grinding hardship of settled life in a wasteland.

The Swiss author Nicolas Bouvier presents fewer obstacles. He is, or was before his death in 1998, more familiar in his outlook and ambitions. He was also a writer with a prodigious gift for describing people and places, with a sharp eye and even sharper wit. If you do not know his writing, you should immediately buy two copies of The Way of the World (Eland, £12.99). You will need a backup as it is a book people will borrow but will not want to return. That first book is an account of Bouvier’s journey with a photographer friend from Serbia to Afghanistan in the 1950s. ‘Travelling outgrows its motives,’ he writes. ‘You think you are making a trip, but soon it is making you — or unmaking you.’

The stories in So It Goes are the final part of Eland’s self-styled ‘homage to this exceptional chronicler of the world’, and they are the mature work of an author who was already, and quite definitively, both made and unmade. They range from finely shaped tales from the Aran Isles and from his childhood with his grandparents, to journal entries from Japan and Korea, encounters in the Scottish lowlands and on Islay, and travel assignments in Xian in the 1980s. Whatever the length, whatever the structure, Bouvier is always a writer of beauty, whose thoughts are engaged with wonder and embellished with observations as clear and fresh as a summer dawn.

Nothing shows this better than his description of a winter’s night on the lump of limestone that is Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Isles. Wracked with fever, his head ablaze with stories of faeries and 6th-century prince-saints, ‘padded like an Eskimo’, he goes for a walk in the absolute darkness ‘to see what this nothing was made of’. What better companion could you want for a fireside night in this long and stormy winter?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in