David Bomberg was only 23 when his first solo exhibition opened in July 1914 at the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea. ‘I am searching for an Intenser expression,’ the brash young painter wrote in the introduction to the catalogue. ‘I hate… the Fat Man of the Renaissance.’ As if to advertise his radical intentions, the first work in the exhibition, the strikingly geometric ‘The Mud Bath’, was hung outside the gallery, facing the street.

Bomberg was endowed with a self-belief bordering on conceit. Born in 1890, the fifth of 11 children of Polish-Jewish immigrants, he spent his childhood in the overcrowded slums of Birmingham and east London. An educational loan allowed him to enter the Slade School of Art in 1911, but he proved an unruly presence; when a professor made disapproving remarks about his latest semi-abstract composition, he hit him over the head with his palette. Funding was withdrawn. He was very ‘blasty’, a friend said later. ‘He wanted to dynamite the whole of English painting.’

By the time the Chenil Gallery exhibition opened, his stock was high in avant-garde circles. F.P. Marinetti asked him to join the futurists; he turned him down. But sales were terrible, not helped by the outbreak of war within a month. Most of the pictures went into storage and remained there until after Bomberg died in 1957, his artistic achievements neglected. To trace his career after the first world war is to be confronted, almost unbearably, with a virtually unbroken series of humiliations and rejections. While he found some late success as a teacher at Borough Polytechnic, with Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff among his students, it’s only in recent decades that his work has been given its due.

Young Bomberg and the Old Masters is a lively one-room show that provides a rare chance to see Bomberg’s most innovative early works together. It also invites us to appreciate how much their creator drew from the art of the past in making them. It opens with a self-portrait in chalk from 1913–14 based on one of Bomberg’s favourite paintings, Botticelli’s ‘Portrait of a Young Man’ (c.1480-5), which is presented alongside it. The artist meets the viewer’s gaze confidently, wearing a shirt he had specially designed to match the one in the original. Bomberg only ever compared himself with the best.

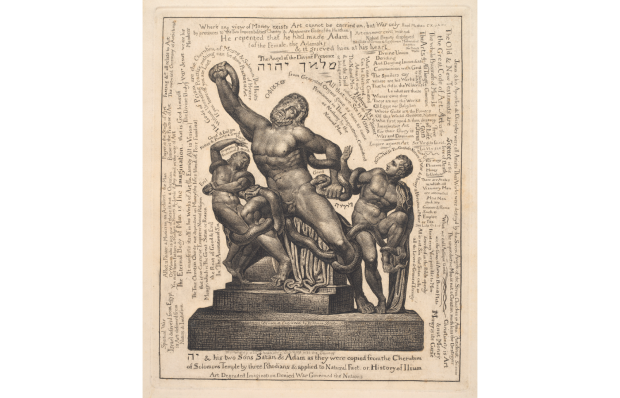

But although he was brazen, he was not destructive. ‘Art must proceed by evolution,’ he declared. His first wife remembered being dragged to the National Gallery to see Michelangelo’s ‘The Entombment’ (c.1500-01): that, said Bomberg, was a ‘real picture’. He revered El Greco for his structural originality; ‘The Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane’ (1590s), acquired by the gallery in 1919, also hangs here.

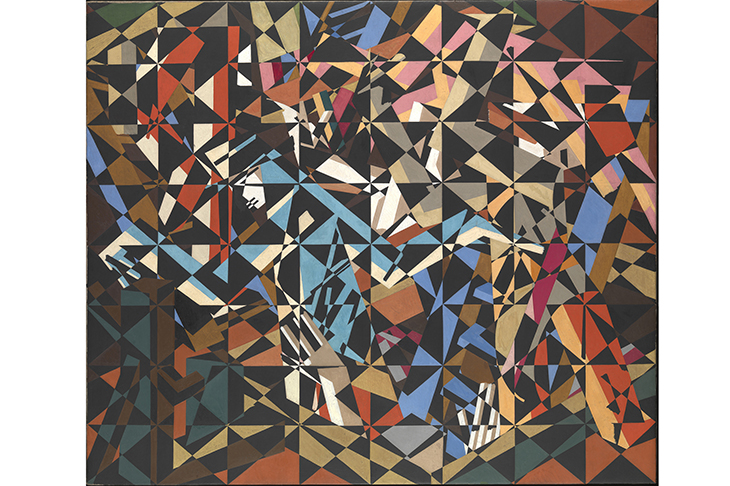

Bomberg learnt from evening classes with Walter Sickert how to square up paintings as a compositional aid. He took the device a stage further, incorporating a grid into finished works such as ‘In the Hold’ (c.1913–14), which depicts immigrants getting off a boat, and ‘Ju-Jitsu’ (c.1913), inspired by the wrestlers at his local gym. These are kaleidoscopic paintings, fascinating to the eye, their ostensibly figurative subject matter — shown clearly in the preparatory sketches displayed alongside them — broken up into countless squares and triangles of colour, emphasising the sense of people jostling within tight spaces: a natural theme for an artist who grew up poor in heavily populated urban areas.

Richard Cork, the curator, points out the way such early works contain echoes of various Old Master paintings elsewhere in the gallery, with the spread arms of ‘In the Hold’s angular blue central figure, for instance, calling to mind those of the naked woman who dominates Veronese’s ‘Unfaithfulness’ (c.1575). A list of other works containing similar echoes — an outstretched arm here, a man bending over there — leads the visitor on a kind of treasure hunt around the gallery. Some of this is invariably speculative, but the overall point is persuasive. While paintings such as ‘Vision of Ezekiel’ (1912) and ‘The Mud Bath’ (1914) represent the peak of Bom-berg’s youthful attempts to distill form to a geometrical essence, in their structural composition — strong diagonal axis, careful arrangement of figures around it — they hark back to any number of older pictures within the gallery’s walls.

By the end of the war, Bomberg was moving towards the vision of nature ‘in the round’ that would characterise his later work. His enormous study ‘Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi’ (1918–19), for a painting commissioned by the Canadian War Memorials Fund, is relatively naturalistic in its depiction of the human form. Nonetheless it proved too original for the Fund’s artistic adviser, who called it a ‘futurist abortion’ with insufficient ‘representational truth’ to be accepted. It was the sort of knock-back with which Bomberg was to become all too familiar.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in