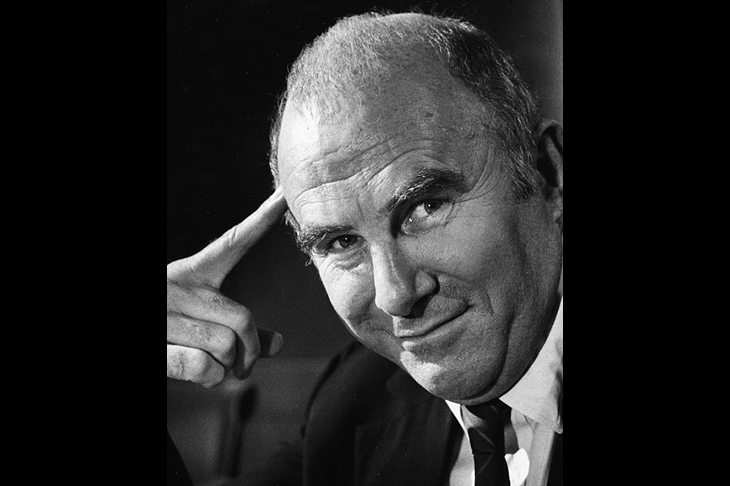

Clive James (1939-2019), in the much-quoted words of a New Yorker profile, was a brilliant bunch of guys. One of those guys was a poet. Alongside the celebrated columns in the Observer, and Saturday Night Clive, and the Postcard From… documentaries, and Clive James on Television, and so on and so forth, there was a lifetime’s outpouring of verse. Ian Shircore’s So Brightly at the Last is the first book-length study of James’s poetry. One sincerely hopes that it is not the last.

Shircore has written books about JFK, on conspiracy theories, and a book about The Hitcher’s Guide to the Galaxy. A friend and an admirer of James — he’s already published one book about James’s work as a songwriter with the musician Pete Atkin — he’s really an enthusiast rather than a critic. Which is not necessarily a bad thing. We can’t all be William Empson. Though we might at least try.

Shircore several times criticises ‘the traditional academic analysis’ of poetry with its tendency towards ‘the plodding autopsy’, but there’s plenty of plodding here: the ‘enduring appeal’ of one poem, we are told, ‘stems partly from its subject matter, partly from its vibrant energy and gusto and partly from an attention to detail in its execution’; another poem is praised for containing ‘so many ideas, so many unexpected images, such potent, unflashy turns of phrase’. Shircore rightly identifies that the most memorable criticism of James’s poetry was written by James himself, in his novel The Remake (1987), in which a character called Clive James ‘writes poetry that sounds the way reproduction furniture looks’. Alas, So Brightly at the Last often sounds, looks and smells like repro crit.

The book mixes Shircore’s readings of a couple of dozen of James’s poems — including ‘The Book of My Enemy Has Been Remaindered’, ‘At Ian Hamilton’s Funeral’, and ‘Injury Time’ — with fond reminiscence and anecdote. This makes for a perfectly pleasant tour of James’s life and work, though with some pretty odd detours. ‘For me,’ confides Shircore, in a typical non-sequitur, ‘the years from sixty to seventy don’t seem to have changed anything. But I lost two of my best-loved and most influential contemporaries, the journalist and media guru Nick Van Zanten and the happy-go-lucky adventurer Will Creavin.’ There are many such random observations, plus lots of curious comparisons: ‘there is something about Clive James that reminds me of Hendrix’. There’s something about Clive James that reminds me of — I don’t know — insert name here.

Nonetheless, for all its eccentricities, the book marks the beginning of what one hopes might be serious studies of James’s work. There’s certainly much essential information here and lots of things I didn’t know, including details of James’s various medical conditions — leukemia, emphysema, kidney failure — which transformed the poor chap in later life, in Shircore’s rather unfortunate though vivid phrasing, from ‘the ebullient, non-stop, globetrotting, motormouth, motor brain Aussie we had known for so many decades into a doomed and depleted invalid’. I did not know that James spent a couple of months in a psychiatric ward during the early stages of his final illness, and I’d forgotten exactly how close he was to Princess Diana.

Also, Shircore’s careful attention to James’s long-forgotten mock heroic sagas of the 1970s — ‘Peregrine Prykke’s Pilgrimage through the London Literary World’, ‘Felicity Fark in the Land of the Media’, ‘Britannia Bright’s Bewilderment in the Wilderness of Westminster’ — usefully reminds us they might perhaps serve as models for writing about our current crises and circumstances. And he rightly acknowledges and generously quotes the criticisms of James’s many detractors, who thought the poetry nothing but meretricious nonsense.

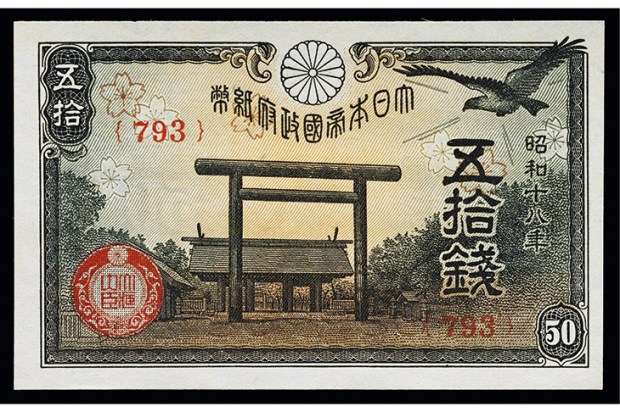

According to Shircore, the reason why James’s poetry hasn’t so far received the serious attention it deserves is because of television. How could readers be expected to take seriously the work of a writer who was famous just for being on the telly? But herein lies the answer to the question: this is exactly why James’s work should be taken seriously. In his reading of one of James’s late poems, ‘Japanese Maple’, Shircore gets it exactly right: one of the reasons ‘Japanese Maple’ is interesting is because it ‘went viral’; ‘The New Yorker website was open, with no paywall to put people off, and the poem quickly notched up a phenomenal 200,000 hits’; ‘Richard Dawkins retweeted it.’ In the 21st century, this is perhaps the closest we can get to poetry as the common language of the common man. Poetry may be the spontaneous overflow of emotion recollected in tranquillity: like a Japanese game show, it is also a media event.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in