The journalist Deepa Anappara turns to crime with her debut novel, Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line (Chatto & Windus, £14.99). First off: great title. I really wanted to love this book, expecting, well, djinns on the purple line. The results are somewhat different. The purple line refers to a train line that runs through an area of an Indian city filled with slums and rubbish tips. Nine-year-old Jai is obsessed with TV cop shows. When young children start to go missing, Jai sets out to track down the people responsible. The hours he’s spent watching programmes such as Police Patrol will now come to good use, as he works a case the real police have little interest in.

As many as 180 children go missing in India every day. This fact prompted Anappara to write the novel. An admirable notion. But there’s a sense of writing from the outside, looking in, rather than starting from the centre: the kid and his obsession with cop shows, and how an intense need to investigate might grow out of that obsession. Nevertheless, great language throughout, colourful, sparkling, packed with images. But man, I’d love to read about djinn patrols on the purple line.

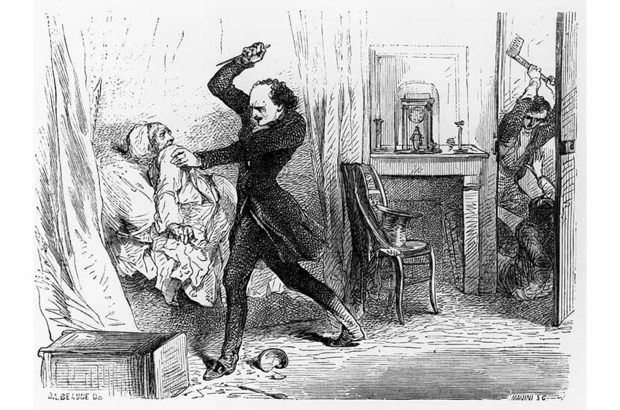

Chris Petit comes to crime fiction from a very interesting angle, having made a name for himself in experimental cinema. His latest, Mister Wolf (Simon & Schuster, £14.99), continues a series set in Berlin during the second world war. By 1944 the city is plagued by political infighting and rising levels of corruption. August Schlegel works at a desk in the Gestapo office, caught between doing what he thinks is right and good, and playing along with the regime. Life on a tightrope. When Adolf Hitler miraculously survives an assassination attempt, Schlegel can’t help but question the official version of events. The Führer’s affair with his niece is tangled into this thread, and the niece’s death seems to be connected in some way with Schlegel’s long-missing father.

Petit is a master of both historical accuracy and imaginative writing. This really is the best of all worlds: action and art working together as one. It’s rare that a book takes such chances with both subject matter and style. The set pieces really sizzle. It’s not an easy read, being dense with ideas in places, but the story always reaches out to the reader even in the most abstract, darkest moments. A unique voice. Crime fiction is well served by writers of this calibre.

Liz Moore’s Long Bright River (Hutchinson, £12.99) deals with the old and trusted subject of siblings with very different lives, and the conflict that ensues. Kacey Fitzpatrick lives on the streets of Philadelphia, locked in a cycle of addiction. Her sister Michaela (Mickey) walks the same streets as a cop. They don’t speak or see each other that much, which causes Mickey much worry, not least because Kacey’s patch is Kensington Avenue, notorious for its opioid crisis. When Kacey disappears, just as a murderer starts to target street people, Mickey becomes obsessed with finding the killer, fearing that her sister might be the next victim.

This is a compassionate tale, full of empathy for the low-lying members of society. Past and present lives are interwoven, giving us a taste of the family drama that led to the sisters splitting apart. There’s good psychology on offer, but the suspense elements lack that final twist of excitement: searching should always be more exciting than remembering. And the novel does suffer from the current fashion for all things miserable. Beware: it’s easy to come away from the final pages feeling despair more than hope.

In contrast, it’s a joy to visit the entire world that Hannelore Cayre conjures in the 205 pages of The Godmother (Old Street, £8.99). Patience Portefeux is a widowed mother, a fluent Arabic speaker who works with the police as a translator of wire taps gathered from North African drug gangs. But she’s poor, and bored, and has little to look forward to. One day she cracks, and decides to use knowledge collected from the tapes for her own ends, earning herself a nice stash of top quality Moroccan Khardala in the process. Working two jobs — as civil servant and drug dealer — is fun and rewarding, but also dangerous, and soon enough both the police and the gangs are closing in.

Plot isn’t the important factor here. The book offers a recollection of disparate events; but what events they are! Witty and surprising, with zero waffle, and written entirely from the centre: character first, politics second or even third, and the story shines for it. Patience walks several marginal zones: French/Arabic, mother/criminal, and most of all, that semi-porous realm where one language meets another. Cayre brings her fully alive. It feels like a one-on-one communion between author and character.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in