British Baroque: it was never going to fly. Les rosbifs emulating the splendour of le Roi Soleil? Pas possible. Still, we had a go and the evidence is assembled in British Baroque: Power and Illusion, Tate Britain’s survey of the art of the Stuart court from the restoration of Charles II in 1660 to the death of Queen Anne in 1714.

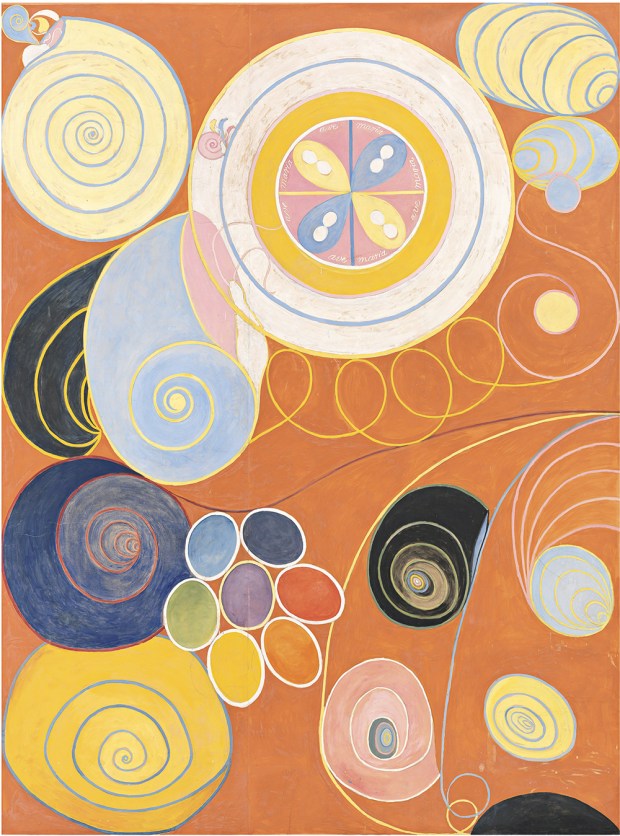

An awful lot happened in those 54 years — the Glorious Revolution, the union of England and Scotland, endless wars in Europe, the rise of party politics — but through it all the Frenchified taste for ‘Wonderful Figures and Whirligigs… that are of no manner of use but to laugh at’ in the contemptuous words of Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, remained constant, and sitters in the portraits of the period kept any signs of change under their wigs.

Oh the wigs! The swags! The fluttering draperies! The flying cherubs! The shepherdesses! The sheep! To judge by the number of baa-lambs littering their paintings, portraitists’ studios must have had petting zoos attached. Even in a royal portrait by Jacob Huysmans, the newlywed Catherine of Braganza is upstaged by a pair of sheep and a family of ducks. No wonder she looks utterly miserable. Welcome to Britain: we love animals; papist princesses from Portugal, not so much.

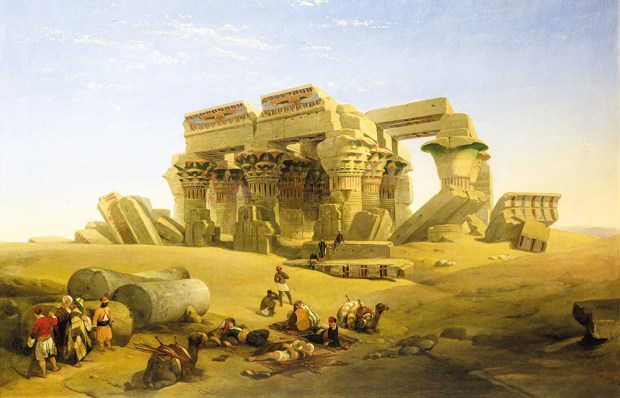

Foreign artists were OK, though. By room two one begins to realise that almost none of the artists in British Baroque is actually British, and to suspect the foreigners — the Italians especially — of taking the piss. The tone is set in ‘The Sea Triumph of Charles II’ (c.1674) by Antonio Verrio, whose depiction of the British monarch as Neptune is the definition of a pyramid of piffle — though in some ways less ridiculous than the French painter Henri Gascar’s portrayal of his brother James, Duke of York (1672–3) as Mars in a gold cuirass tied with a royal blue ribbon and sky-blue silk leggings teamed with jewelled lilac sandals.

By these standards, the women are conservatively dressed. True, Peter Lely’s 1664 portrait of the King’s mistress Lady Castlemaine dressed as the Virgin with one of her five illegitimate royal children playing the Christ Child does seem shocking, and contemporary visitors may avert their gazes from Benedetto Gennari’s 1684 painting of Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin — another royal squeeze — posing bare-breasted as Diana with a passel of black child slaves and hunting dogs all sporting the same metal collars.

Whether garbed as shepherdesses, goddesses or saints, the women look depressingly alike. There can be nothing duller than a pageant of long-dead beauties, and between Sir Peter Lely’s Windsor Beauties, Sir Godfrey Kneller’s Hampton Court Beauties and Michael Dahl’s Petworth Beauties this exhibition exhumes the relics of three. Only the young Willem Wissing, a former assistant of Lely, injects some life into his subjects. His refreshingly simple portrait of ‘The Hon. William Cecil’ (c.1686) captures the radiance of childhood a century before Thomas Lawrence, and his elegantly coloured full-length of ‘Queen Anne, when Princess of Denmark’ (c.1685), conveys a sense of youthful promise dissipated by the time of Dahl’s 1702 portrait of the grumpy Queen. Wissing’s own youthful promise would be snuffed out by his sudden death aged 31. If he had lived, British Baroque might have rocked.

A room of trompe l’oeil paintings comes as a relief, with a marvellously deceptive door from Chatsworth decorated by Jan van der Vaart with a painted violin hanging off a real brass peg, and an exquisite picture of ‘Six Butterflies and a Moth on a Rose Branch’ (c.1690) by the Scottish-born William Gouw Ferguson, a native talent lost to Baroque Britain when he swam against the artistic current and moved to Holland. But it’s in the field of architecture that British Baroque comes into its own. Unfortunately, plans and models of buildings by Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor are no substitute for the real thing; ditto designs for murals — another sphere in which an Englishman, James Thornhill, would excel. Thornhill may have been saved from the worst excesses of the French and Italians by his British sense of humour: in an undated sketch for a mural of ‘The Birth of Venus and the Gods of Olympus’, a Peeping Tom in contemporary dress ogles Venus from behind a pillar.

After that it’s back to the portraits, where among the Whigs in wigs in the final room the hitherto unremarkable Kneller suddenly pulls off a brilliant bravura portrait of the independent-minded poet-diplomat Matthew Prior. You wonder why the sitter looks so alive until you realise he’s not wearing a wig. The year after it was painted in 1700 this Westminster joiner’s son was expelled from the Kit-Kat Club for turning Tory, but perhaps his real crime, in this age of power and illusion, was to ditch the wig and drop the pretence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in