In 1576 Venice was gripped by plague. The island of the Lazzaretto Vecchio, on which the afflicted were crammed three to a bed, was compared to hell itself. In the midst of this horror Tiziano Vecellio, the greatest painter in Europe, died — apparently of something else.

He was in his eighties and working, it seems, almost to the end. Titian: Love, Desire, Death, which was briefly on at the National Gallery, before it was closed down this week by our own plague, contained several of the greatest masterpieces of his old age — and also of European art. It comprises just seven canvases, all done for Philip II of Spain — a villain of English history, the man who launched the Armada, but as far as Titian was concerned his most discerning patron. Philip was an avid persecutor of heretics but happy to give his favourite artist a free hand. He was rewarded by some of Titian’s most audacious work.

To ‘review’ such supreme paintings is slightly absurd. These are the touchstones from which Rubens, Velazquez and Rembrandt learnt and their successors still do. Van Dyck actually owned ‘Perseus and Andromeda’; Lucian Freud confessed that he, too, would have liked to have had one of these Titians on his wall. He couldn’t choose between ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and ‘Diana and Callisto’, which he considered jointly ‘simply the most beautiful pictures in the world’.

Frank Bowling, a contemporary master of abstraction, returns again and again to ‘The Death of Actaeon’ — in part because he finds it so modern. ‘There’s something amazing in the stirring up of the paint,’ he told me. ‘It just comes across at you — whoosh! — like a De Kooning.’

That’s absolutely right. These late pictures are executed with a looseness and freedom that startled 16th-century viewers such as Giorgio Vasari, who found Titian’s late manner ‘judicious, beautiful, and astonishing’. That was spot-on too, including the point about judiciousness.

In places these pictures might look as if they were done with a flying brush, but in fact they are preeminent examples of slow painting. According to eye witnesses, Titian would begin a work, then lean it against the wall. Some time later he would scrutinise what he had done as if it were a ‘mortal enemy’, add a touch or two, set it aside again to dry — and so on until he was satisfied. The process could take years. This was why there is a controversy about whether some of his last works — such as ‘The Death of Actaeon’, which was never delivered to Philip — were finished or not.

Perhaps Titian himself hadn’t made up his mind. For him, one suspects, finishing a picture was a delicate decision, as it is for many contemporary artists. This was partly because he had no standardised approach. All of these pictures contain carefully finished passages — the faces, for example — but also magnificently wild ones. The fountain in ‘Diana and Callisto’ spurts like a jet of water by Francis Bacon.

Water in all its forms was one of Titian’s special interests. In these paintings you find the calm, sparkling sea on which Europa is being carried away, but also the mirror-like pond in ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and the churning waves around the sea monster menacing Andromeda.

He also made lifelong studies of soft, living flesh and the varied textures of cloth. In ‘Venus and Adonis’, the seated goddess’s naked buttocks are dimpled from pressure — a detail much admired in the 16th century — and modelled with precision. But the sheen of scarlet velvet on which she is sitting is rendered with a few strokes of the brush that might have taken a minute or two to execute.

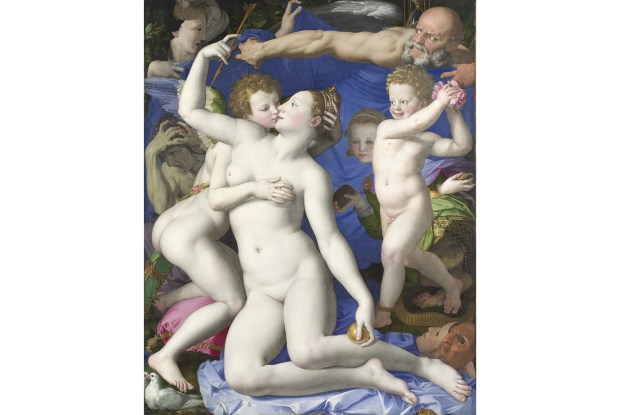

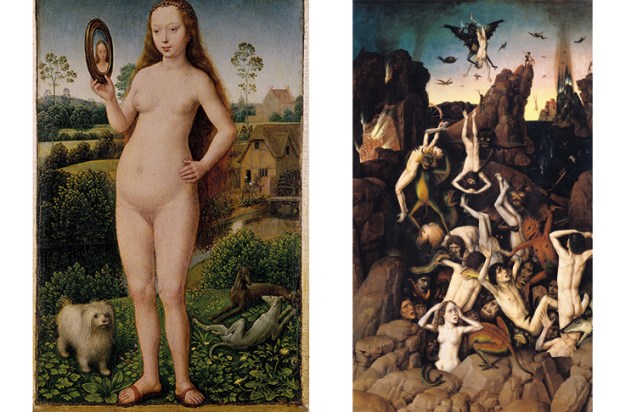

In writing to Philip, Titian called this set of pictures ‘poesie’ — poems in paint. They are largely derived from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and deal with transformations: from life to death, from love to loss. These myths are dark. Jupiter adopts the form of a bull to force himself on a princess named Europa. Diana turns Actaeon into a stag for the crime of having accidentally seen her naked, so he is torn to pieces by his own dogs.

Here, then, are depictions of tragedies and crime scenes, but also immensely pleasurable images. Towards the end of his life, Titian was taxed by a visitor to his studio with having made the repentant Magdalene too ‘dewy and fresh’. He replied that he had painted the saint on the first day of her desert fast, so as ‘to paint her as a penitent indeed, but also as lovely as he could’.

Titian did that, time and time again, in every part of these visual poems. Figures, animals, landscapes, lust, mortality, sensual bodies, clouds — everything is painted as compellingly as this great artist was able. No one has ever done so better.

Let’s hope the exhibition returns after the current plague ends.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in