When Sajid Javid resigned in a row with No. 10, there was much speculation about what would be in the coming Budget. No one, though, predicted that it would end up being overshadowed by coronavirus.

The short-term economic effects of this outbreak are almost unknowable. It is still hard to work out how serious it is going to be. One of those drawing up the government response plan tells me they would be happy if, in a year’s time, people thought they had wildly overreacted. Boris Johnson once said that the mayor in Jaws — who keeps the beaches open despite reports of a shark — was his hero for resisting the clamour for action. But now that he is in Downing Street he has no intention of taking a similar risk.

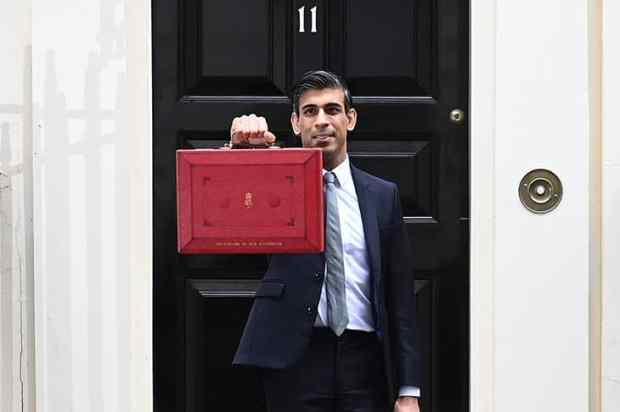

With stock markets in turmoil, the feeling is that now is the time for a slimmed-down Budget. Rishi Sunak, the new Chancellor, has three big statements this year: this Budget, the spending review and the autumn Budget. It would be sensible to wait until later, when the uncertainty should have eased, to make big fiscal policy decisions.

The overwhelming focus of the Budget will be delivering manifesto promises: the extra 50,000 nurses, the 20,000 police, overhauling the much-abused ‘entrepreneurs’ relief’. In Downing Street they know that trust is a huge issue for both the government and Boris Johnson personally, so they want to show that they are keeping their promises.

Some analysts predict that the economic hit of coronavirus will be comparable to the 2008 financial crisis. But even if that’s the case, a fast rebound is expected — though, as Kate Andrews writes in her feature, it may well accelerate the move away from complex global supply chains.

One of the big questions of the last election was why the Tories smashed through the so-called ‘red wall’. Was it just Brexit, and the preference for Boris Johnson over Jeremy Corbyn? If so, there’s a risk that without Corbyn to scare the bejesus out of traditional Labour voters, they might drift back. But if it was down to other, longer-term factors, then the Tories have a chance to use successive Budgets to secure a new electoral coalition over the next four years.

The mayoral elections in May will help clarify things. When the Tories triumphed in the West Midlands with Andy Street and in Tees Valley with Ben Houchen it was a precursor to last year’s general election result. But they both won with slim majorities. If they can get re-elected, it will suggest the Tories can consolidate their red wall gains.

Houchen’s aim is to bring steelmaking back to Teesside (as he tells Katy Balls in her feature). Street is one of HS2’s biggest champions and views better transport as key to ‘levelling up’. He has published a fantasy map of what he wants the West Midlands transport system to look like in 2040: a Brummie version of the London Underground. It would cost £15 billion, he says. When I visited recently he showed me around by public transport to demonstrate how much better connected the area is becoming. He raced away from our meeting to talk with a firm he is trying to persuade to open a ‘gigafactory’ to make electric car batteries.

Street is up against Liam Byrne, a former Labour cabinet member. The contest will be the first evidence of how the Tories fare against post-Corbyn Labour. The race will be tight, but the early signs are promising for Street. The West Midlands turned to the Tories in December out of a sense that Labour had taken it for granted: it will take more than a new party leader to change that. Street is an assiduous campaigner — and not shy about boasting that his links with the government mean he’d be in a far better position to secure infrastructure projects than any Labour mayor. (He has already had the new Chancellor up to visit.)

The one area where Street is out of step with Boris Johnson is Brexit. Street is still pushing for a softish Brexit deal that minimises disruption to pan-European supply chains. Undoubtedly, the biggest electoral risk No. 10 is taking is its belief that it can get the borders ready by the end of the transition period. As the resignation of the Home Office Permanent Secretary Sir Philip Rutnam showed, this will not be easy and it will expose tensions in Whitehall. It will require the state working at a pace seen as almost unachievable by the Sir Philips of this world.

We have not had, yet, much of a sense of the post-Brexit economy this government is trying to foster. The next few months should change that. We should expect to see an emphasis on science, infrastructure and the regions. Rishi Sunak is a longstanding advocate of free ports. Those of us who have known him for many years remember that much of his argument for leaving the EU was, from the offset, about the benefits of having a nimbler economy.

Johnson and Sunak are as different personalities as you would expect from people whose major intellectual influences are, respectively, classics and economics. But they share the same vision of Brexit and green issues. Both believe in clean tech, not hair-shirting. They think the way to achieve net zero is through innovation rather than attempting to return to some pre–industrial age. They both calculate that there are economic opportunities in shifting to new, more environmentally-friendly forms of transport and production. They point to Britain’s track record: our carbon emissions fell by 29 per cent over the past decade, faster than in any other developed country. Tech, rather than rationing, led this change.

The coronavirus has, for now, suspended normal politics. By the time it has passed, the Labour party will have a new leader. The Tories will have to work out how to hold their new coalition together without the adhesive that Jeremy Corbyn provided. That will require a political economy that is genuinely concerned about raising up the regions rather than taxing London and the south-east more. They will have to show that this new Toryism is not Labour-lite, but an attempt to encourage a new innovation-led economy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

SPECTATOR.CO.UK/podcast

James Forsyth and IPPR North’s Sarah Longlands on levelling up the north.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.