‘Coronavirus Fears Are Decimating The Sex Industry’, ‘Sex Workers Bracing For Income Loss During Coronavirus Pandemic’, ‘Sex Workers Are Facing Increasingly Risky Conditions As The Coronavirus Spreads’.

Headlines such as these have been circulating over the past few weeks as health fears, strict travel bans, decreased job security and “social distancing” guidelines have caused demand in prostitution to plummet globally, leaving sex workers – who are predominantly women – with little or no income to support themselves and their families.

Brothels and sex on premises venues have now been included in the closures in Australia, though it is unclear how this will apply to street prostitution (which is legal in New South Wales), or other methods of selling sex, such as the hundreds of online advertisements that appeared within hours of the new measures. In some European cities, like Geneva and Stuttgart, the entire practice has been temporarily banned to help combat the pandemic.

While some prostitutes are turning to online work such as video calls and sexting, others are continuing to provide services with further hygiene precautions. While the primary goal of the additional precautions seems to be putting their clients’ minds at ease, sex workers are also concerned about their own health and that of their families.

A greater fear being expressed across the industry is that due to the dramatic drop in demand, these women are at higher risk of exploitation by clients who will take advantage of their desperation by pushing for lower prices, for not having to screen and for “unsafe work practices”, such as sex without a condom or pushing the personal boundaries of what the woman is willing to do.

Adelaide-based sex worker Anya says she has already been asked, “will you do this for this much money”, because clients know she’s in a vulnerable position. Sherae Lascelles, who runs a community organisation supporting street-based sex workers in Seattle, says she’s already hearing reports of more violent and coercive behaviour from men who are using the virus as leverage and is fearful that “this is going to get people killed”.

Sex industry campaigners in Amsterdam have also voiced concerns that Dutch sex workers risk being trafficked as the shutdown of Amsterdam’s sex clubs is likely to drive the trade underground.

The reality is however, that health risks, exploitation, violence and trafficking are already endemic in the prostitution industry and the fears being raised about the impact of COVID-19 only serve to reinforce just how misogynistic, exploitative and dangerous it is for women, and how now, more than ever, it needs a complete overhaul.

Research shows that women are prostituted because they are vulnerable due to poverty, marginalised backgrounds, a lack of educational and employment opportunities and as a result of previous abuse. Inside the industry, they face physical and sexual violence, as well as associated health traumas including STIs, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative disorders, depression, eating disorders, substance abuse and suicidality. Studies and country reports show that prostitution and trafficking are inextricably interlinked.

Prostitution is sexual exploitation. It is the commodification of (mostly) women’s bodies by (mostly) men and the reduction of women to mere body parts. In addition to the lived experience of prostitutes, this is confirmed by sex buyers themselves: “Being with a prostitute is like having a cup of coffee – once you’re done with it, you throw it out”; “If I am satisfied with what I am buying, then why should I be violent? I will be violent when I am cheated, when I am offered a substandard service”; prostitution is “renting an organ for ten minutes”.

Given this objectification and dehumanisation, the violence, degradation and exploitation prostituted women experience is hardly surprising, whether during a coronavirus pandemic or otherwise. It is clearly not “a job like any other” and most people who are not already desperate, vulnerable or otherwise coerced, would not be willing to assume the risks involved. One international study found that 89 per cent of sex workers wanted to escape the industry, but felt they had no other options for survival.

Like advocates overseas, sex industry advocates in Australia are calling on the government to provide emergency financial support to prostitutes during the coronavirus lockdown, who in addition to suffering lost income, have no employee benefits to fall back on, due to their generally self-employed, casual, non-citizen or unlawful status.

There is no doubt that like many others, sex workers are suffering financial adversity in the current climate and will need help. But instead of simply keeping them afloat during the pandemic so that they can ultimately return to a life of violence and exploitation, it is clear that our government must do more to provide them with real and enduring support.

The most effective assistance for sex workers is seen under the Nordic Model of prostitution legislation. Pioneered in Sweden in 1999, it has since been adopted by Norway, Iceland, Canada and France among others. The Nordic Model criminalises the buyer of sex only and in addition to providing social and economic support for those wishing to exit the industry, it has also shown to dramatically decrease the incidence of trafficking.

Implementing the Nordic Model throughout Australia is the best way to protect sex workers from health risks, exploitation, violence, trafficking and financial hardship, and would mark a long-overdue recognition by our government that the existence of prostitution is rooted in gender inequality, that it violently commodifies women and that despite claims by sex industry advocates, by its very nature, can never be made “safe”.

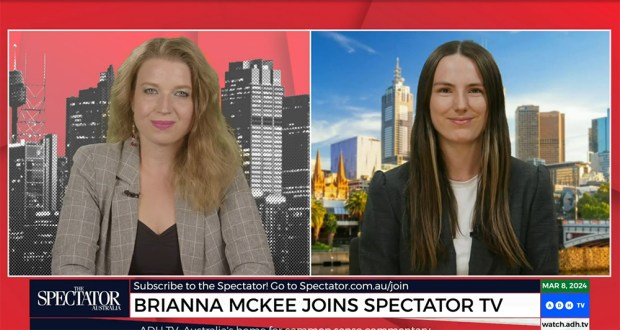

Rachael Wong is the CEO of Women’s Forum Australia and an adjunct lecturer in the school of law at the University of Notre Dame Australia.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in