The Covid-19 pandemic shows all too clearly the importance of data. Knowing that men and older people are more likely to die and that certain ethnic groups are also more at risk is worrying but vital information. Without accurate data, we are flying blind. In England and Wales, men are around twice as likely as women to die from the disease. But do fears about wading into the gender debate mean that crucial statistics are not being collected properly?

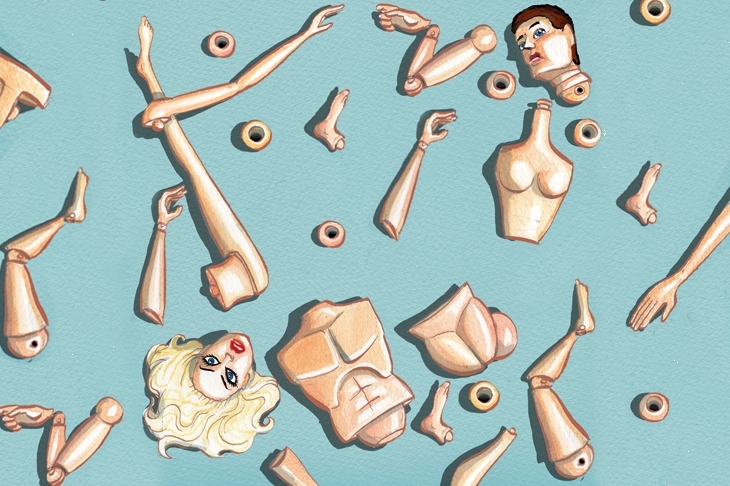

Despite the fact that it is more obvious than ever that sex matters, both government and researchers are failing to collect proper data on sex. A recent academic survey on coronavirus and health illustrates the current confusion about sex. Instead of asking respondents whether they are male or female, it gives six response categories, including ‘gender fluid and non-binary’. Yet people who identify as ‘gender fluid’ come in two sexes, just like the rest of us. It seems unlikely that the virus cares whether you are gender fluid, and it’s highly plausible that ‘gender fluid’ males and females have different experiences of labour market discrimination and domestic violence according to their sex. We can respect the identities of trans people without pretending that sex does not exist.

Mortality is not the only stark reminder of the salience of sex. Caroline Criado Perez has drawn attention to the fact that personal protective equipment is designed with male dimensions in mind, leaving many female frontline staff wearing unsafe, ill-fitting gear. Women and men are also experiencing different social and economic impacts due to the lockdown. Mothers are bearing the brunt of homeschooling, with inevitable consequences for their paid work. Domestic abuse of women has increased, with a reported rise in the number of women murdered.

Sex is a fundamental demographic variable which affects almost every aspect of our lives. Yet for some time now, government agencies have been quietly replacing sex with gender identity in their data collection. For example, guidance published jointly by the Government Equalities Office and ACAS advises organisations who are bound by law to report annually on their gender pay gap to provide data on their employees’ gender identity, not their sex. This has the potential to greatly skew the data, since a small number of highly-paid males identifying as women could make a firm’s pay gap appear much smaller than it actually is. The bias will be exacerbated if people who identify as trans are concentrated in particular sectors, as seems to be the case – for example, two per cent of staff at the BBC are trans.

This number may seem astonishingly high, but it’s important to bear in mind that trans status does not imply any medical intervention, rather simply an assertion of gender identity. What’s more, if an employee ‘does not identify with either sex’, ACAS advises they can be omitted from the data. This means, for example, that a highly-paid banker might simply be omitted from statistics. Collecting data on people’s gender identities may well be useful in addition to sex. The problem occurs when gender identity is conflated with sex.

Police forces now record crimesdone by men as though they were committed by women at the request of the perpetrator. Again, this is likely to skew the statistics for certain crimes, particularly those crimes overwhelmingly carried out by men. Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures for England and Wales show that 94 per cent of convicted murderers and 97 per cent of individualsprosecuted for sexual offences are male. Meanwhile, trans identification among men convicted of custodial offences is certainly high enough to affect the data: one in 50 male prisonersin England and Wales identify as trans.

The UK census has collected data on sex since its inception in 1801, yet the census authorities plan to advise respondents to the 2021 census that they may answer the sex question according to their gender identity. This will damage the ability of the census to monitor inequalities between women and men, and to assess the sex-differentiated impacts of Covid-19. The 2021 census will be remembered as the Covid census. It should provide a unique opportunity to analyse the impact of the pandemic across social groups. It would be unfortunate if that opportunity was placed in jeopardy through the unforced error of muddled guidance on the sex question.

I was heartened to see the emphasis placed on data analysis in Liz Truss’s recent speech setting out her priorities as minister for women and equalities. But data analysis stands or falls by the quality of the data. Without data on sex, we cannot develop evidence-based policy to tackle inequalities between men and women.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Alice Sullivan is professor of sociology at University College London

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in