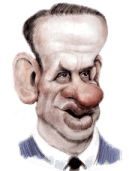

Turnbull: Adam Bandt in a better suit

The problem with reviewing Malcolm Turnbull’s book is where to begin. How about in recognising my manful service to the nation? I’ve read it so you don’t have to. For much of its 698 pages it resembles a superhero comic, as we follow Malcolm’s daily battle for truth, justice and the Green way against the evil forces of Tony Abbott, Peta Credlin, Rupert Murdoch, Alan Jones, Andrew Bolt and anyone else who doesn’t believe in 100 per cent renewable energy. The super-villains also include Scott Morrison, Mathias Cormann and Peter Dutton, who committed the original sin of not making Turnbull prime minister for life.

After his party room voted him out in August 2018, Turnbull spent the next 12 months searching through his WhatsApp records to fit up Morrison as the new Kevin Rudd, an habitual leaker and media manipulator.He would have been gleefully rubbing his hands together at the harbourside mansion, screaming out to Lucy, ‘I’ve found another one, I’ve found another one’, in anticipation of a month of front-page headlines denouncing his Liberal party successor.

Alas, he picked the wrong apocalypse. Having said the world will end through climate change, the biggest threat to mankind turned out to be coronavirus, which relegated Malcolm’s book to page 7. It was like the Road Runner and Coyote, with ScoMo beep-beeping his way to political immunity. In fact, the great Rudd similarity is with Turnbull himself. It’s not just the narcissism, scheming and egomania. In the formative influences of their childhoods, Turnbull and Rudd are psychological doppelgängers. In Rudd’s 2017 memoir Not For The Faint-Hearted, we read about the devastating impact of his estrangement from his father. The drinking, carousing, knockabout Bert Rudd had no time for his nerdy son. Thereafter, Kevin just wanted to be loved, which was fine, until June 2010 when the Labor party caucus unloved him in favour of Julia Gillard.

Turnbull’s experience was similar. When he was ten his mother shot through to live with a university professor in New Zealand. This left a huge hole in Malcolm’s life that wasn’t filled until a decade later, when Lucy stepped in as a new mother figure. For Rudd and Turnbull, these emotional voids produced personality traits of self-absorption and self-pity. In both their memoirs, there is no room for self-deprecating humour, just a constant, ultra-serious search for redemptive adulation, plus the shared habit of blaming the Murdoch media for their woes. Freud would have a lot to say about these two. For reasons the author never explains, Turnbull’s A Bigger Picture keeps returning to the subject of sex. There’s the Barnaby Bonking Ban, of course, but also snide reflections on eight other colleagues. The gratuitous attempt to damage the National party’s George Christensen is particularly disgraceful. In 2010 Gillard promised to unleash ‘the Real Julia’. In this book we discover the Real Malcolm – maniacal on every front. At page 170 he admits to a mental illness and by the book’s end, no reader can doubt the truth or seriousness of his condition. At page 9, reflecting on his father’s experience, he writes of ‘a good lesson learned at a young age: don’t belittle people’. But then he spends the next 650 pages belittling people, even allies like Julie Bishop. It’s not ‘a bigger picture’ at all.

In media interviews, I have been asked how my book, The Latham Diaries (2005), compares to Turnbull’s. The main difference is in outlook. My book became a publishing prophecy, more than a diary. It called out Kevin Rudd as a sociopath, something ministers from his own government subsequently confirmed. It also forecast huge problems for Labor from the corrosive impact of machine politics – the emergence of a divisive, bickering sub-factional system internally. As the Rudd and Gillard governments (2007-13) unravelled and disintegrated, my analysis started to look like a crystal ball. Turnbull’s chief charge against the Liberal party is that a dangerous, extreme ‘right-wing rump’ will destroy it. But already, this looks spurious. The conservative Liberal MPs who voted to remove Turnbull in 2018 were vindicated, stunningly so, by the 2019 federal election result. Ideologically, the extremism is all Turnbull’s. The Real Malcolm has outed himself as Adam Bandt in a better suit. He supports the immediate closure of Australia’s coal industry, thereby creating rust-bucket regions in the Hunter Valley and Central Queensland. He admits to spending $11 billion of Commonwealth money on Snowy 2.0 solely for the purpose of generating electricity at a different time of day, disguising the weaknesses of wind and solar energy. Turnbull takes pride in having helped to establish the Guardian newspaper in Australia, importing Corbynism to our country. Tethered to his Green-Left view of the world, he has ‘no issues with the ABC for bias, as so many of (his) colleagues had’. When, as Prime Minister, Tony Abbott condemned Islamic State for its ‘beheadings, mass executions, crucifixions and sexual slavery’, Malcolm regarded this as ‘almost hysterical’ and actually ‘helping the terrorists’.

The real question for the Liberal Party was never about so-called Del-Cons. It was the incendiary influence of the Turnbull Non-Cons. How did a majority of Liberal MPs ever make this man their leader, not once but twice? He was, in effect, Australia’s first ever Green prime minister. If this were merely an aberration, an unwanted political fluke, many of us would break the current virus restrictions and re-open a pub or two to celebrate. But it’s not. In the NSW Parliament, I’ve encountered many Turnbull-type MPs, ‘moderate’ Liberals and Nationals who believe in the renewables religion, political correctness and divisive identity politics. The disease is not just in Malcolm’s memoir. It has marched through the institution of the Coalition parties and imperilled the best of Australia’s economic and cultural traditions. The book is bad. The threat to our nation is even worse.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in