This is Roger Scruton’s final book. Parsifal was Wagner’s final opera. Both works are intended to be taken as Last Words: testaments of belief at the end of a long spiritual journey. In the introduction, Scruton identifies the enduring problem in his life, and ours, as: ‘How to live in right relation with others, even if there is no God.’ He gives us his answer:

Whether or not there is a God, there is this hallowed path towards a kind of salvation, the path that Wagner described as ‘godliness’, the path taken by Parsifal, and it is a path open to us all.

The path of our salvation, then, can be seen in the opera.

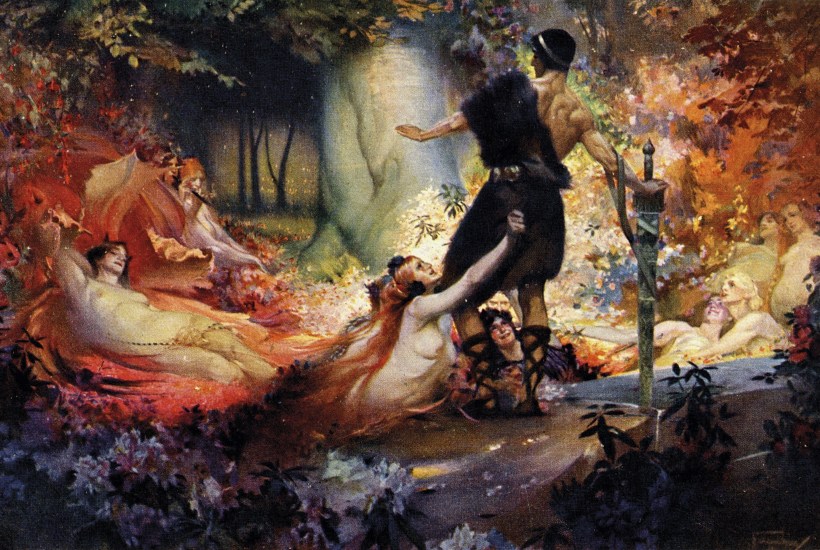

Parsifal is a retelling of the Grail legend. The plot in brief: King Amfortas is the guardian of the Holy Grail and the spear which pierced Christ on the cross. The evil magician Klingsor covets the power invested in the holy relics. He sends Kundry to seduce Amfortas and while that’s going on, Klingsor steals the sacred spear and stabs Amfortas. The wound never stops bleeding. It can only be healed by a holy fool. Enter Parsifal (Sir Percival in the Arthurian version). He’s a huntin’, shootin’ sort of chap (as Scruton was himself) and makes his entrance taking a pop at a swan.

Taught the error of his ways, he is wakened to the possibility of compassion towards innocent animals and fellow men. Klingsor sends Kundry and a whole garden of flower maidens to seduce Parsifal, who remains chaste. Miraculously catching the holy spear that Klingsor hurls at him, Parsifal touches Amfortas’s sacred wound with it. Christ’s spear resumes its role as the redemptive instrument. The wound is healed. Parsifal is crowned king. The world is redeemed.

The opera has attained sacred status. It is performed on Good Friday. Wagner called it Buhnenweihfestspiel, music that consecrates a stage. Nineteenth-century devotees fasted and prayed before a performance. Today, it is as bad form to applaud after the first act as to applaud in church.

So why did Scruton and Wagner, both avowed non-Christians, perceive redemption to be found through this piece? Wagner’s answer, expressed in his 1880 essay ‘Art and Religion’, is that only art can satisfy our inchoate religious need in a post-religious world. Scruton, for whom there could be no such thing as sin because he didn’t believe in God, sees Parsifal as a tale of redemption from the corrupting bondage of erotic love, a cleansing of the ‘shame that emerges spontaneously from sexual desire’. I had no idea such sad puritanism still existed these days. Parsifal, he says, ‘touches the mysterious longing for purity in all of us’. We are all, apparently, yearning for salvation and we can only heal the existential wound that is our existence when we, like Parsifal, reject eros, erotic love, for Mitleid, compassion. Compassion for the dead swan, compassion for the wounded king. Love thus treated as a summons to sacrifice becomes the sacred, redeeming force. The self is redeemed when lifted to a perceived higher cause. Through compassion we are not condemned to mortality but consecrated to it.

Tosh! said Nietzsche, who, like the Stoics, found enforced compassion an offence against the equal dignity of human beings, elevating the moral superiority of victimhood through glorification of the downtrodden. Nietzsche didn’t trust much in holy fools either. ‘Is Wagner a man, or is he rather a disease?’ he asked, furious at the opera’s doctrine, but helpless to resist the ‘dangerous fascination, the sweet, shuddering infinity’ of the music. Sweet shuddering infinity was exactly what Wagner wanted to achieve. He called opera ‘a chaos that confuses the senses’, but ever since 1933, books on his operas can’t resist trying to analyse exactly how Wagner achieves his magical confusion.

Scruton is no exception, employing extensive musical and musicological analysis. A large part of the book is devoted to unpicking the musical ‘how’. Wagner was the father of the leitmotif, a technique later enthusiastically taken up by Hollywood, in which a musical phrase is associated with a certain character or a certain emotion. The leitmotif plays whenever that character or that emotion is present, or to be evoked. Scruton numbers 52 of these and correlates all of them to the plot. This can result in quite a lot of sentences such as: ‘The struggling fool. A variant of 41B, but with a bass-line recalling 15.’ Only for the specialist. But if you are not of a musical bent, skip the musicological last couple of chapters and you can still find enormous satisfaction in following the journey of one of our great philosophers making sense of his own life though another’s sublime work of art.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in