Sweden has been the world’s Covid-19 outlier, pursuing social distancing but rejecting mandatory lockdown. Schools, bars and restaurants are open – albeit with strong voluntary social distancing compliance and streets that often look almost as empty as Britain’s. Has this been enough? Sweden’s public health agency has now published a study of its R number, a metric which the UK is using to judge the success of the lockdown. The UK objective is to push R below one, by which it means it wants the number of new cases to fall. Last week, the UK’s R number was estimated at 0.8 (± 0.2 points), a figure described as an achievement of lockdown. But Sweden’s reading is 0.85, with a smaller error margin of ±0.02pts.

This raises an interesting question: might voluntary lockdowns work just as well? And might they keep the virus at a manageable level with lower social and economic costs?

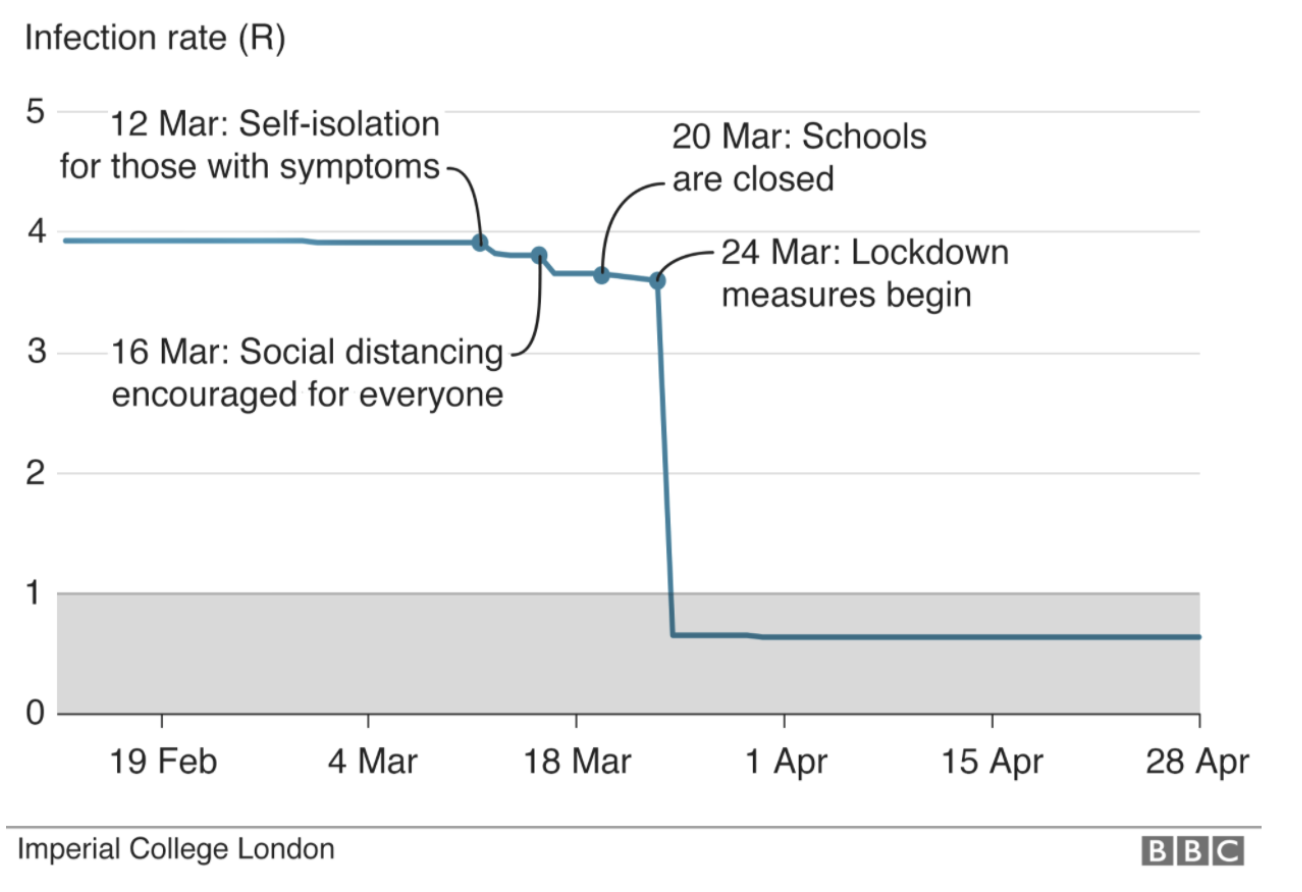

The UK government has used modelling from Imperial College London, which makes some clear assumptions about lockdown. Imperial’s graph, reproduced below, shows its argument: shielding, voluntary social distancing, even school closures are shown to make very little difference to the spread of the virus (ie, the R number). But lockdown, by contrast, is shown to be a game-changer with “the R” sinking immediately. This graph below, if taken at face value, makes an open-and-shut case for lockdown.

But is it true? We don’t know because “the R” is notoriously difficult to pin down and not published in Britain. But Imperial also applied its UK assumptions to Sweden, warning that its rejection of lockdown was likely to leave the virus rampant with an R of between 3 and 4. That is to say: every person infected would give it to three or four others. Its modelling envisaged Sweden paying a heavy price for its rejection of lockdown, with 40,000 Covid deaths by 1 May and almost 100,000 by June.

The latest figure for Sweden is 2,680 deaths, with daily deaths peaking a fortnight ago. So Imperial College’s modelling – the same modelling used to inform the UK response – was wrong, by an order of magnitude. Sweden has now published its own graph, saying its R was never near the 4 that Imperial imagined. More importantly, its all-important R level (all-important to the UK anyway – it has never much featured in the Swedish discussion) has in fact been below the safe level of 1 for the last few weeks.

As Johan Norberg has written, Imperial’s model ‘could only handle two scenarios: an enforced national lockdown or zero change in behaviour. It had no way of computing Swedes who decided to socially distance voluntarily. But we did.’ Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s state epidemiologist, has seen his trust ratings soar. Some Swedes are even having his face tattooed on their arm.

When Imperial first made its models, everyone was guessing. We know more now. Every day, in The Spectator‘s Covid-19 email, we bring new studies that add more detail to our understanding of the virus. At present, Britain is considering the South Korean model: an ambitious combination of tech, surveillance, track and trace. But given that Sweden achieved what Imperial College had thought undoable, without the surveillance or the tech or the loss of liberty, its lessons are also worthy of consideration.

Sweden’s Prime Minister has said he is relying on ‘Folkvett’ – people’s wit, or common sense. As Boris Johnson considers his options, he should also ask whether a folkvett option – described in a recent Spectator leading article as a ‘trust the public’ approach – might work for Britain.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in