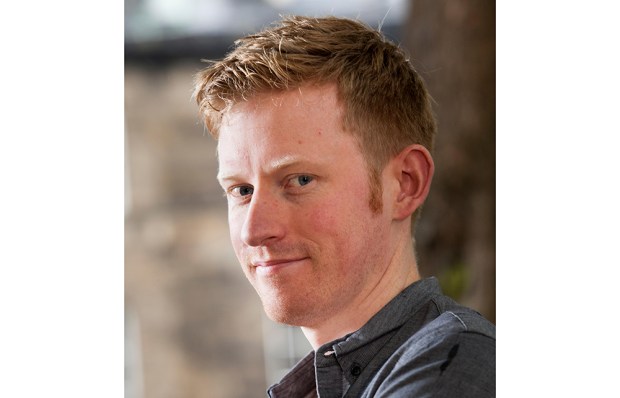

Dara McAnulty is a teenage naturalist from Northern Ireland. He has autism; so do his brother, sister and mother — his father, a conservation scientist, is the odd one out. This book records a year in the life of a gifted boy in an unusual family. Minutely detailed observations of birds, insects, trees and weather are woven into an ecstatic description of the unrolling of the seasons. It is also an impassioned and original plea for protection for ‘our delicate and changing biosphere’.

The diary is valuable in several ways. The writing of it is necessary to Dara himself, his means of processing his experiences. When he’s outside, absorbed in nature, he’s mentally storing his observations. Only later, through writing, can he make full sense of what he has seen, heard, touched, smelled, tasted. ‘What started as scribbles and scratches on the page has grown into an essential shape in my days.’

He helps the neurotypical reader to understand what it feels like to be autistic. Dara and his siblings are ‘high-functioning’ — verbal, academically able. It’s easy to make the mistake of thinking that this is ‘mild’ autism, not a big problem. Dara puts us right:

I often imagine a canopy of leaves above my head, protecting me from the world. More often than not, though, it doesn’t work. The humiliation builds into despair. I get completely exhausted by the amount of energy spent taking deep breaths, ignoring remarks, weathering punches. By solstice in June I’m like Scarecrow on the way to Oz, his straw insides hollowed out.

Bullying and incomprehension are not his only difficulties. Autistic intensity is overwhelming; listening to a corncrake ‘crexing’, thinking about the destruction of its habitat, Dara is suffused with ‘loneliness and despair’. But the immersive joy that is the positive version of this intensity is enviable. On the cliffs of Rathlin Island during the breeding season,

everything gloriously slams into you at once…guillemots, kittiwakes, razorbills, fulmars and puffins, all wheeling or diving, patrolling and protecting, sauntering over the shoulder of the stack. Mind-blowing. Magnificent. This is a place vibrating with survival and endurance. I feel tickled and almost hysterical, but must take it all in.

Dara is a campaigner in the youth movement against climate change. He has mixed feelings, not about the cause, but about his role within the campaign and the effects of social media; his autistic honesty persuades us to trust his judgment. His painstaking observations of the natural world make the diary the opposite of a knee-jerk response. He understands profoundly the inter-

connectedness of nature and humankind. On autumn:

The land, although in a state of slow withering and soft lullaby, is bursting from the ground. Life is connecting under our feet, mycelium strands interweave, bearing fruit from darkness. Fungi. Fruits of the forest. Every day we walk over their invisible formings, unaware of their necessity for life on earth.

The diary is a study of his home patch, almost a junior version of Gilbert White’s Selbourne. It begins in the west, in County Fermanagh, where Dara observed the small patches of wilderness surviving between over-tended suburban gardens. Then the McAnultys move east, to County Down. Given the autistic dread of change, the move inevitably begins as trauma, but proves fruitful. There are mature trees in the garden and a forest park across the road. It’s a modern housing estate, but Dara sees goldfinches and bats and silver Y moths; and his new school is overlooked by the granite peak of Slieve Donard, the highest of the Mourne Mountains: ‘I felt embraced by it. Slieve Donard would be with me every day.’

Dara is as responsive as any Irishman to the mythology and poetry of his homeland. From a pilgrimage to Glendalough to connect with St Kevin, ‘my blackbird saint’, to celebrating Samhain — Celtic New Year— amongst forest trees, to thinking of Seamus Heaney when he puts his hand into a bog pond — ‘If I dipped my hand the spawn would clutch it’ — the diary celebrates human response to nature:

I love these stories. They enrich my life as a young scientist… we need these lost connections, they feed our imagination, bring wild characters to life and remind us that we’re not separate from nature but part of it.

When you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person, as the useful saying goes. Having autism doesn’t automatically result in this close bond, but it often does involve an obsession, or passion, of unusual strength and depth. Dara, whose name means ‘oak, wise, fruitful’, has done a public service in revealing his autistic passion to us. And Little Toller Books are to be congratulated on having the wisdom to publish this lovely and remarkable book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in