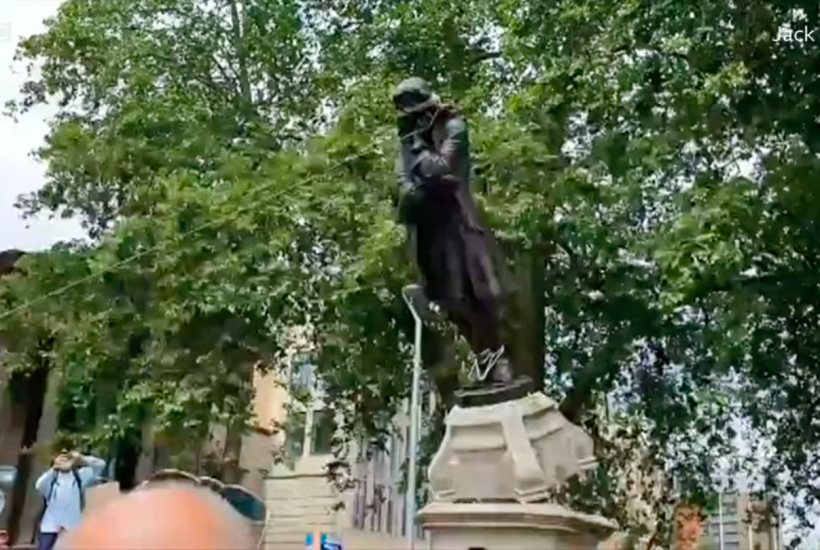

It doesn’t matter how good your intentions are, it’s your process that counts. The push to topple a statue of Edward Colston did not begin at the spur of the moment this weekend. Campaigners have argued for years that the Bristolian slave trader was not a man to be lionised. You don’t have to be especially woke to wonder why a monument to a man who made his fortune off the brutalised backs of human beings was still standing in a British city in 2020. Reconsidering those we memorialise and whether they ought to be honoured seems a timely task.

But the just and proper way to go about it is debate followed by democratic decision. The resulting discussions would draw attention to historical injustices and give the public an opportunity to meditate on them before putting the matter to a vote in town halls or local referendums. Where a removal resulted, it would be an explicit rejection of past wrongdoing and an implicit resolution to do better.

Those who tore down Colston have denied us that debate and denied themselves too. The liberal press will run a few columns about his villainy and Newsnight will put on a panel but otherwise the conversation will be about the actions of the vandals. Very little mention will be made, incidentally, of George Floyd. His name does not even appear in the Guardian report on the statue.

One of the reasons mob justice is no justice is because it disdains rules and process and an iconoclasm without either will quickly run into trouble. To rework the old relativist saw, one person’s icon is another’s graven image. It’s all very well the police standing by while left-wing protestors yank down Colston because he was a slaver, but what happens when a far-right rabble comes for Nelson Mandela’s statue on the pretext that he was head of uMkhonto we Sizwe? Radicals might say that different standards ought to apply to racist and anti-racist rioters, but even if a law-based order could tolerate such caprice, it would require those radicals to invest rather a lot of confidence in the very police they want abolished.

Should iconoclasm extend to figures who espoused racist views? I would scrap Roald Dahl Day on the basis that the children’s author was a frothing anti-Semite. (‘There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity… Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.’) Celebrate his books, sure; but not the mad old Jew-hater who wrote them. Again, though, implications can quickly outstrip intentions. Keir Hardie’s newspaper railed against the ‘hook-nosed Rothschild’ and ‘Rothschild leeches’ and accused them of orchestrating wars for their own financial gain. If I want Dahl Day gone, don’t I have to concede the removal of the Labour party founder’s bust from outside Cumnock Town Hall? And if Hardie Must Fall, there can be no grounds for leaving the Arch of Titus standing in Rome. The 1st century marble structure was erected by Domitian to commemorate his brother Titus’s sacking of Jerusalem and destruction of the Second Temple. Arco di Tito honours the killing, exile and enslavement of Jews. When do we start swinging the wrecking ball?

Once you begin taking corrective action against historical sins, you will realise just how much correcting is needed. Marie Stopes International will obviously have to change its name, which honours a eugenicist who advocated laws ‘to ensure the sterility of the hopelessly rotten and racially diseased’ so that ‘our race will rapidly quell the stream of depraved, hopeless and wretched lives’. What about authors whose works contain bigoted language and stereotypes? It’s all very well telling libraries and bookshops to stop stocking Philip Larkin (racism), Charles Dickens (anti-Semitism) and Laura Ingalls Wilder (anti-indigenous), but what if they refuse? The logic of statue-levelling would suggest that storming the bookshelves and tossing the offending tomes in the bin is a legitimate response.

Some would go further than the icon-smashers can imagine. Karl Marx’s statue-topped grave has been repeatedly vandalised and daubed with the words ‘architect of genocide’. His ideas have had the misfortune of immiserating and killing large numbers of people wherever they have been put into practice but isn’t that all the more reason to remember him? Tearing down memorials to historical villains causes me the same unease I feel when old TV shows bowdlerise racist, sexist or homophobic scenes: in wiping prejudice from the record, don’t you erase the evidence from public consciousness?

None of the foregoing questions are intended as gotchas. I am open to a reassessment of who we venerate and whether some should now be properly contextualised rather than blindly celebrated. But we require clear terms of reference and an appreciation that historical revisionism isn’t easily contained; we all revere someone others revile. If we are to embark on a course of revision, it matters a great deal how we go about it. We must insist on rules and process, the guardrails of ordered liberty, rather than the frantic convulsions of the mob.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in