This column has been banging on about the peculiar nature of Huawei, the Chinese telecoms giant, ever since its expanded presence in the UK won what I described as ‘grateful applause from David Cameron’ back in 2012. I have deployed everything from serious intelligence sources to laborious knock-knock jokes (‘Huawei who?’ ‘Who are we kidding, prime minister? We don’t need to knock on your front door when we’ve already got a backdoor device in the Downing Street switchboard’) to make my point that the proliferation of Huawei kit in UK telecoms networks represented an obvious but unquantifiable security risk. Which means I can’t disagree with the government’s belated decision to exclude Huawei from the UK roll-out of 5G, though the ban does not extend to 70,000 roadside boxes of switching equipment for domestic lines, so we’ll never really know whether they’re still listening.

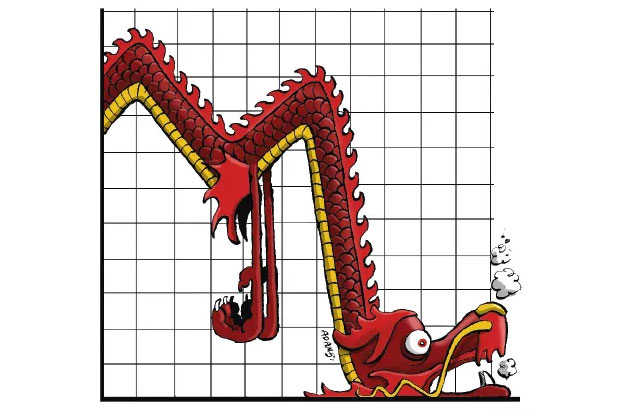

The change of policy comes in response to pressure from Washington and from Tory backbenchers, itself fuelled by China’s harsh new security regime in Hong Kong and increasingly jingoistic tone. We’re told it will delay 5G by two years and as BT boss Philip Jansen has said, the more extensive the replacement programme, the more likely there are to be technical glitches — and the greater the impact on UK competitiveness as a whole. Combine substandard broadband and mobile service with billions of extra business costs for post-Brexit border controls, the withdrawal of Chinese investment from other infrastructure projects and recessionary pressure to create more jobs rather than automate, and we’re looking at five more years in which UK productivity gets worse rather than better.

Like so many important policy choices, the Huawei decision would have been better made much earlier, when allies such as Australia and New Zealand as well as the US were already looking askance — while London’s great and good queued to be recruited as Huawei ‘advisers’ (‘Huawei who?’ ‘Who are we going to buy this week in the House of Lords?’). But not even the Chinese have invented a technology that equips ministers with firmer judgment and forward vision.

A kick for world trade

It’s probably too late to throw my weight behind Peter Mandelson’s maverick bid for the director-generalship of the World Trade Organisation, since Downing Street has already endorsed Liam Fox as the UK candidate. Fox’s sole claim — having made near-zero impact as Theresa May’s international trade secretary from 2016 to 2019 — is that as a well-known Atlanticist and oddball right-winger he might at least earn himself a White House photo opportunity, even if it has to be a masked one. But since Donald Trump has expressed nothing but scorn for the WTO and done his utmost to cripple it, that connection would hardly help the organisation rise to the twin challenges of boosting post-Covid global recovery while facing down China’s hyperaggressive intent to trade only by rules of its own making.

By contrast, the Mandelsonian combination of guile and snake-charm — honed when the former Labour eminence moved to Brussels as EU trade commissioner — might have stood a better chance. Meanwhile, the other declared candidates (most predictably, former Nigerian finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is the bookies’ favourite) represent the usual suspects of turgid international bureaucracy, while Brazilian incumbent Roberto Azevêdo will depart early leaving no trace behind.

The truth is that the WTO, like the World Health Organisation, is an institution that ought to have a pivotal role in its field but has somehow failed to gain traction and authority. The only director-general really to give it oomph was the first one, back in 1995: that was Ireland’s formidable Peter Sutherland, who once told me his simple guiding principle, learned from his father, was: ‘If the ball is at your foot, kick it.’ World trade in all its aspects, rules-based and otherwise, certainly needs kicking forward now.

Duty free

Until 1997, Stamp Duty was charged on house sales at 1 per cent above a £60,000 threshold and did little more than cover the cost of Land Registry bureaucracy. Since then, renamed Stamp Duty Land Tax, it has become increasingly complex, onerous and significant to Treasury coffers. Having contributed just £3.7 billion in 2000/1 it rose to a peak of £13 billion in 2017/8, thanks to higher rate bands up to 7 per cent introduced by George Osborne to capture a slice of the rampant London property market that was being driven by foreign cash. Back then, tax tinkering was all about balancing the books while causing the least offence to Tory voters: if more could painlessly be harvested in SDLT, more could also be given away in cuts to the inheritance and income taxes the middle classes hated.

In the current crisis, however, Rishi Sunak’s tax manoeuvres are not about balancing the books at all but leaving them for the next generation to sort out while using every available tool to stimulate economic activity. Hence a temporary lift in the SDLT threshold until 31 March from £125,000 to £500,000, freeing nine out of ten home-buyers from paying the duty — at a cost of £3.8 billion, a droplet among current dizzying budget numbers. The TaxPayers’ Alliance (which campaigns for abolishing SDLT) reckons the change will stimulate a surge in sales that would settle to an extra 132,000 transactions in a full year — with obvious benefits for builders, estate agents, garden centres and the mobility of buyers and sellers to find work in new places.

That last factor will be hugely important in the years ahead: why not make the SDLT change permanent and take the threshold to £1 million? Meanwhile, I’m glad to know the Chancellor shares my love of dining out. His offer of £10 vouchers to do so is wisely for August only but I’ll have plenty more readers’ tips for you before it expires: this week’s most exuberant praise was for Donna Margherita on London’s Lavender Hill.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in