For three months art lovers have had nothing but screens to look at. As one New York dealer complained to the Art Newspaper in May, ‘Everything is so flat — except for the curve,’ referring to the infection rate.

Flatness isn’t such a problem for paintings, which are flat anyway, or for digital media obviously. The art form that has suffered most from the lockdown is sculpture, since no 360˚navigation technology yet invented can replicate the experience of walking around a 3-D object. So it’s fortuitous that Gagosian is unlocking its three London spaces to a trio of new exhibitions of 3-D works, under wraps since March.

Crushed, Cast, Constructed at Grosvenor Hill contrasts three approaches to sculpture in the works of John Chamberlain, Urs Fischer and Charles Ray. The main space is occupied by three of Fischer’s massive silvery forms moulded from small lumps of clay kneaded, squeezed and twisted in the hand, then scaled up 50 times for casting in aluminium. The last time I saw examples of these tortured metal clumps magnifying the epidermal ridges on the artist’s palm to the size of ribs on a side of beef was in Paris in 2011, plonked down in the courtyard of the Rodin Museum beside ‘The Gates of Hell’. There is certainly something Rodinesque about the torsion of these inchoate forms, with their hints at human and animal shapes: a giant knee here, a protruding foot there, a nose, an ear, an eagle’s back, a sea lion’s snout. They’ve been compared to ancient rock formations, but no human hand can beat wind and weather at natural form. Despite their fancy tongue-in-cheek titles after Stéphane Mallarmé’s fashion magazine bylines, they are basically sculpture about sculpture.

Charles Ray’s sculpture is about a particular object he’d like us to look at more closely: a dilapidated 1938 Cletrac tractor found rusting in a backyard in San Fernando Valley which he took apart, recast piece by piece, and painstakingly reassembled in gleaming aluminium. ‘Tractor’ (2003–4) is a pretty thing, though rather pointless; just as Fischer’s enormous casts don’t justify their size, Ray’s elaborate reconstruction doesn’t repay his effort. But John Chamberlain’s ‘Untitled’ (c.1967) is a satisfying 3-D object in itself.

In the late 1950s Chamberlain, too, started tinkering with motor vehicles, painting, crushing and welding metal car parts together in expressionist arrangements as bright and upbeat as bouquets of spring flowers. The more sober monochrome piece on show here dates from the following decade after he moved on to crushing galvanised steel boxes, including the occasional cast-off of Donald Judd’s. I like the idea of Judd’s fastidiously minimalist boxes being broken up for recycling, and I wished Chamberlain was still around to go to work on the hideously overdesigned toothpaste-blue Ferrari I passed on the way home, squatting outside the Ferrari showroom in Berkeley Square like a monstrous arthropod from Planet Zog.

Chamberlain died in 2011 but perhaps Piero Golia, the Neapolitan-born conceptual artist showing in Britannia Street, would like to have a go. In 2003, after writing off his Saab, Golia melted it down and recast it as a unicorn; five years later he used three bulldozers to compact a bus to fit a six-metre booth at Art LA. His four contributions to this small show are more modest: an endlessly spinning roulette wheel with a marble ball too light to settle in a pocket; a two-minute film of distant lightning with an oversized projector; a totem-like woodcarving impregnated with mushroom spores promising to sprout shiitakes during the show’s six-week run (good luck with that, mate, we’ve had a ‘mushroom log’ for years and it’s still a log); and a single red tulip in an exploding blue glass vase. The timing of the explosions is unpredictable, but when you’re born in the shadow of a volcano (as Golia was) so is life.

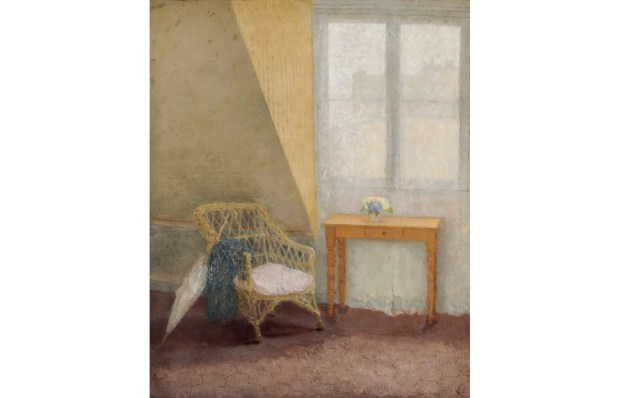

The Davies Street show also has a Neapolitan twist, featuring reproductions of furniture designed by the Italian writer Curzio Malaparte for the iconic modernist house he built for himself in 1937 on a craggy promontory in Capri. Born Kurt Erich Suckert, the half-German Malaparte (a play on Bonaparte) mythologised his second world war experiences in two extraordinary novels, Kaputt and The Skin, which still have the power to shock. His Capri house acquired celebrity status after Brigitte Bardot was filmed by Jean-Luc Godard in Le Mépris in 1963 sunbathing on its roof wearing nothing but a paperback. The simple furniture — a table, a bench and a console made of beautifully shaped and polished walnut on fluted columns of marble, travertine and spiral-carved pine — has been reproduced by his youngest descendant Tommaso Rositani Suckert in the hope of keeping the Malaparte flame alive. I hope whoever buys it reads his novels, though that might make the furniture harder to live with.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in