The only memorable argument I have ever heard in that tedious debate about whether Shakespeare was a Catholic came from the poet Tom Paulin. I remember him claiming in a lecture that the ‘bare ruin’d choirs’ sonnet must have been written by someone who had seen the despoiled monasteries, desecrated churches and ravaged holy places of a faith of which they were a part. Famously, such an argument only gets you so far, for by this logic Shakespeare was also a king, empress, ex-king, sailor, magician and fool, among many hundreds of others. But part of the rationale stayed with me. Which is that the bitterest truth of all is that loving a thing does not mean you can protect it, and that even the things you consider most sacred can be trampled over.

This may seem a slightly histrionic way to return to the subject of what the national church is doing in the era of Covid. But it feels appropriate to me after news of the closure of my family church.

Long-term readers might know of my conflicted, not to say confused, attitudes towards religion. The last Church of England vicar in whose congregation I regularly sat once broached the subject with me over the post-service coffee. ‘I don’t like to ask. I mean it really isn’t my business,’ he began. I eventually pulled it out of him. He had read something about me online and someone had referred to me as an atheist. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he stuttered out again, ‘I shouldn’t have said anything. It’s not my business.’ ‘It really is,’ I assured him. ‘More than anyone’s really. It’s complicated,’ I added. ‘Isn’t it?’ we agreed, and both did some circulating.

Still, whether in a period of belief or unbelief I always imagined that the Church would remain. I suppose I feared a last stand, at Little Gidding or the like. But while I imagined people deserting the Church I never conceived of the Church deserting itself, of it shutting the doors and just sending the congregations away.

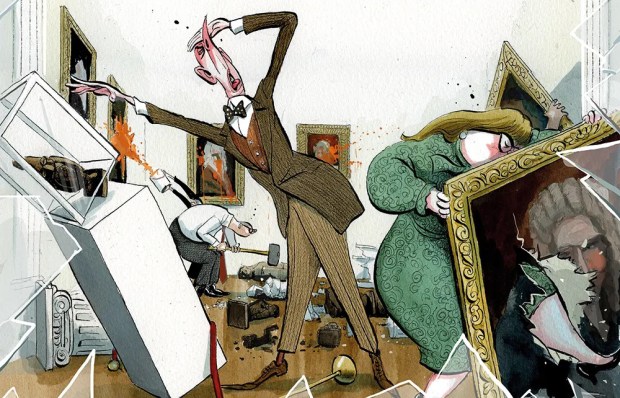

I first went into St Margaret’s, Westminster as a very young boy. My family had done one of those migrations that might be familiar to other members of the Anglican communion. At our local church the choir that first taught me how to read music was summarily scrapped. A new vicar brought in the guitars and microphones. Soon a drum kit loomed. Common Prayer and King James were out, of course, and new hymns and worse liturgy came in. Soon the walls were whitewashed, the carpet was down and the vicar gave his ‘talk’ sitting on the altar, swinging his legs. The Murrays were off.

We migrated to St Margaret’s because a local state school that my brother and I both attended had a side-deal in providing choristers to the church. The school went south, but the church and choir remained, and we remained with it, always grateful to have washed up there. We’ve been there the best part of 40 years now. And though an increasingly irregular congregant myself, I had rather assumed that it would go on. Worship had been uninterrupted on the site for some 900 years. Pepys had worshipped there. Churchill was married there. As a chorister I used to try to see what Lady Thatcher put in the collection plate on her visits.

Even when its own chorister tradition started to slide, a professional adult choir continued to provide exceptional music to a grateful congregation. The organist of many decades — Thomas Trotter — was one of the world greats. He introduced the congregation to music we might never otherwise have found. We never took any of this for granted, unusually sitting through the whole of the closing voluntary, and applauding warmly at the end.

The congregation, too, was of an unusual kind. Being the church of the House of Commons there always used to be a certain attendance by MPs and peers. Less so in latter years, especially after John Bercow messed with the Speaker’s chaplain arrangements. Still, a reliable number came through. And in an era that worships diversity for its own sake, the congregation of St Margaret’s was genuinely, unforcedly diverse by nature. We had all washed up there in different ways. Some came because it was the parliamentary church; others because it was their parish church. The council estates and peers commingled in worship, music and preaching of the highest order. When Donald Gray or Roger Holloway preached, you listened, learned, and what they said stayed with you.

The church closed throughout Covid, like churches across the land. And then the announcements came. In recent days it was announced that the choir was disbanded. Then that the services of the organist were no longer needed, other than on any future special occasions. Then the worst blow: Sunday services would be no more. With one great sweep the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey declared that if the 200-strong congregation of St Margaret’s still wanted to worship in future then they could join the queue next door to see a service in the Abbey. So an utterly unreconstructable and real community is unnaturally dismantled and scattered. I suspect similar stories are about to be replicated across the country.

A few weeks back, after I wrote about the closed churches, some readers might have noticed that a letter both sniffy and silly appeared in the following issue. Bishop Beverley Mason and three of her colleagues pooh-poohed my fears about the churches that had self-closed so readily and stayed closed after the garden centres and fast-food restaurants had reopened. These bishops boasted about all their online activity. I never doubted that there have been some terrific Zoom calls. Just as I never doubted the Church of England’s ability to organise food banks. What I doubted was their ability to keep their own faith alive. And so I turn back to the bare ruin’d choirs sonnet, and ‘the twilight of such day / As after sunset fadeth in the west’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in