Travelling around Latin America three years ago, Stephen Chambers was attracted by pharmacy signs with pictograms advertising treatments to illiterate customers, and on his return he painted a series of serio-comic pictures of fatal diseases from the plague to bird flu. Could he get a gallery to show them? Could he hell. They all complained that they weren’t ‘cheery’ enough.

Art is particular: loves death, hates sickness. Look at the first world war: an inspiration to cubism, futurism, vorticism, expressionism and dada. And the Spanish flu? Forgotten. In the face of death from disease, the avant-garde that sharpened its cutting-edge on conflict retreated.

Artists who were personally affected painted it. It inspired two miserabilist self-portraits by Edvard Munch, who survived, and a tender drawing by Egon Schiele of his dying wife, made days before he succumbed himself. It left no mark on the art of Paul Klee, who shook it off; he was more affected by the clean-lined Bauhaus aesthetic, itself a response to public health concerns about overstuffed, germ-ridden Victorian furniture.

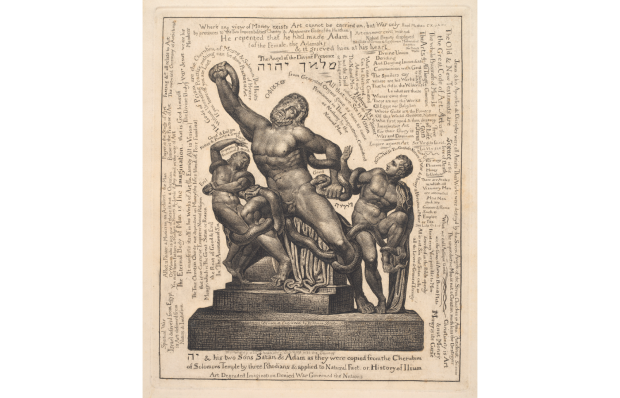

War is dynamic, sickness is supine; injecting life into the subject isn’t easy. In the past there were traditional approaches to choose from, starting with apotropaic images of saints. The poster boy of this tradition was St Sebastian, the patron saint of plague victims, taking the arrows of airborne disease into his body and surviving to die another day. Mantegna painted his first image of the saint in Padua, possibly after recovering from the 1456 plague himself. Titian wasn’t so lucky; his many portrayals of the saint didn’t save him from succumbing in old age, some say, to the Venetian plague of 1575–7, a epidemic so grave it demanded not just a votive painting but an entire church, Il Redentore, designed by Palladio.

In a secular age, this approach no longer works: St Sebastian is powerless, with truncated head and limbs, in David Wojnarowicz’s collage ‘Bad Moon Rising’ (1989), made at the height of the Aids crisis. The moralistic approach has had its day too. No more medieval ‘Triumphs of Death’ over a sinning humanity, a sad loss to the darker side of art. It’s in this tradition that the Austrian symbolist Alfred Kubin’s ‘The Spanish Sickness’ belongs, with its scything skeleton — the only contemporary image by a fine artist to address the subject of the Spanish flu directly. But Kubin was a throwback to the gothic era, obsessed with death from the age of 19 when he attempted suicide on his mother’s grave. Interestingly, his spine-chilling drawings of plagues and epidemics doubled, trebled and octupled their estimates at Sotheby’s last June. It must have been something in the air.

By comparison, contemporary responses to Covid have been mind-numbing. The banality of Hirst’s ‘Butterfly Rainbow’ and ‘Butterfly Heart’ prints is, I suppose, excused by the fact that they’re raising money for charidee, like the 10,000 face masks printed with sunflowers seeds and middle-fingered salutes by Ai Weiwei. But Banksy could try harder than those mask-wearing rats with the jokey tagline ‘If You Don’t Mask, You Don’t Get’, so much less cool than the simple, unaffected slogans of Keith Haring’s anti-Aids poster campaign.

Like its lasting effects, the lasting art of Covid may not emerge until later — and then, I suspect, from the studios of lesser-known artists. For the time being even the celebs are hunkered down, professing to enjoy their solitude. Tracey Emin has been in happy self-isolation making sentimental drawings for her online White Cube exhibition, I Thrive on Solitude (until 2 August). Hirst, with no teams of assistants to marshal, has been painting; Antony Gormley has been modelling little men out of clay. Marc Quinn, meanwhile, has been churning out ‘Viral Paintings’ at the rate of one a day, printing off screenshots from his iPhone newsfeed and spattering them with paint. Will his prices octuple 100 years hence? I doubt it. As Grayson Perry observed about submissions to his C4 Art Club: ‘I don’t think people want to look at pictures of coronavirus all the time’, not even now.

What most of us want is a way of making imaginative sense of it all. At the start of lockdown I reread The Decameronwith its account of the 1348 plague in Florence — in which Boccaccio’s father and stepmother died — and its collection of shamelessly escapist stories. When I suggested it as a theme for a show to some artist friends, they jumped at the chance of escape from self-absorption. The resulting exhibition, Revisiting the Decameron, is on the Flowers Gallery website (until 9 August), and includes work by Susan Wilson, Marcelle Hanselaar and Shani Rhys James (see page 27). As one contributor, Jiro Osuga, commented: ‘Perhaps what we need at such times is not morbid self-flagellation, pious platitudes or sugar-coated sentimentalism, but the uninhibited exercise of the imagination.’ The Decameronembraces all of human life, with its terrors, delights, hilarities and hypocrisies. There is room for sickness too: Stephen Chambers’s paintings have found a home in the show.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in