Credibility contrasts: Paul Keating and John Fahey

Just as well Paul Keating is only a feather duster so whatever he says these days about the Reserve Bank doesn’t amount to a row of beans – apart from encouraging a heap of economists to spring to the Bank’s defence against his latest ‘extraordinary attack’. In it, he damned the Central Bank’s ‘indolence’ during the Covid-19 crisis in failing to support the government’s budgetary funding measures – just as its ‘indolence’ had worsened the 1991 recession for which he as Treasurer had been wrongly blamed. But not according to former Reserve Bank board member Warwick McKibbin; ‘Keating is the wrong person to be criticising the Bank when he was the one who caused the recession of 1991’.

With a nod to a 31-year-old controversy, one of the Bank’s defenders, AMP economist Dr Shane Oliver, says ‘Keating seems to be leaning in the direction of putting the independent Reserve Bank in the pocket of the Treasurer’. But this time Keating’s unwelcome intervention will prompt no disastrous consequences, unlike his boast as Treasurer to a 1989 press conference that the supposedly independent Reserve Bank ‘do what I say’ and, to a dinner, that he had the Bank ‘in his pocket’. This, in the words of his ‘mate’, Reserve Bank chairman Bernie Fraser, affected ‘the Bank’s standing in financial centres around the world…[as] critics even (falsely) impugned sinister overtones in my ‘mateship’ with Paul Keating…some suggesting that Mr Keating only had to get on the phone to me and I would do his bidding’.

Even worse, according to another former Bank governor, Ian Macfarlane, the Bank’s consequential lack of credibility was a cause of the failure of the Bank’s policy framework in the 1990s; ‘Each of the monetary policy easings of 1990 and 1991 were met by the charge that they were done for political reasons… There was clearly great distrust of monetary policy… [with] the Bank compelled to keep a low profile…[due to] the widely-shared perception that the Central Bank had not been in charge of its own policy decisions, that it had been little more than the hand-maiden of the Hawke Labor government and especially of its Treasurer Paul Keating’. As a source of advice on the Reserve Bank, Keating carries too much baggage to be taken seriously.

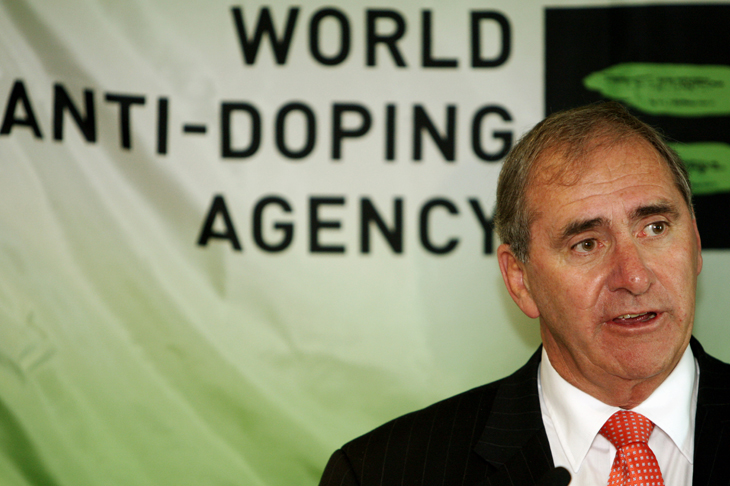

‘If there is a heaven, John Fahey is definitely going there,’ observed a fellow non-believer as we joined the faithful outside St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney last week following the two-hour Mass celebrated by Archbishop Fisher. It was not simply that John Fahey was a devout Catholic recognised by the Pope last year with the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Gregory the Great, but also that Christian principles (and Catholic dogma, often to his political disadvantage) had been to the fore in his many years of dedicated public service – and as a committed family man. As premier of NSW, finance minister for the first half of John Howard’s prime ministership, head of the World Anti-Doping Agency and integral member of Sydney’s successful bid for the 2000 Olympics, chancellor of the Australian Catholic University, Fahey left an impressive legacy for a childhood immigrant in a struggling working-class family from New Zealand. And his recovery from the near-death experience of losing a lung to cancer that ended his political career in 2001 enabled him to continue his public service on top of the family responsibility that saw he and his wife Colleen change from grandparents to effective parents after the tragic death of their youngest daughter.

But political success is not achieved without political intrigue. Fahey’s entry into Liberal party parliamentary life was, to put it kindly, devious and at my expense – for which I ultimately became truly grateful. In the March 1983 federal election, I had lost my very marginal seat of Macarthur (and my job as Treasurer Howard’s parliamentary secretary). But in the polling booths encompassing the state seat of Camden, then held by Labor, I was ahead by several thousand. With a state election due the following year, Liberal opposition leader Nick Greiner, backed by the Liberal state organisation, asked me to give up my federal ambitions and stand as a ‘certain winner’ in Camden. Reluctantly I agreed, and so immediately sought from the president of the Camden Branch, John Fahey, a readily given assurance that he and his branch had no problems with this. But vested interests relating to the possible creation of an airport at Badgery’s Creek intervened. Out-of-the-way Liberal branches that were little more than shells were quietly given the kiss of life and suddenly John Fahey decided to stand – and narrowly defeated me for preselection. This defeat brought a greater reward; its unpleasant aspects ensured enough support for my subsequent preselection (ahead of Bronwyn Bishop, among others) for the Senate for that year’s election, enabling me to continue (albeit in opposition) my interrupted federal political career and ultimate appointment as Australia’s Consul-General in New York.

In an ironic reward for Fahey saving me from state parliament, I engineered his move from Macquarie Street to Canberra. After leading the coalition to defeat by Bob Carr’s Labor in the April 1995 NSW election, Fahey resigned the Liberal leadership and determined that his political career was over. However, as the March 1996 federal election loomed, it became evident that for John Howard to win, he needed Labor-held Macarthur back in the fold. Unfortunately, the locals had already preselected an uninspiring candidate and I convinced John Howard that if we replaced him with the locally very popular Fahey, the seat would fall into our lap.

Fahey, feeling an obligation to the Liberal party and expressing strong support for Howard, eventually agreed to stand for Macarthur, with the then-endorsed candidate withdrawing to be rewarded with a comfortable seat in the NSW Legislative Council. And on election to federal parliament Fahey was immediately appointed Finance Minister, where his kindly, chatty disposition camouflaged the tough financial discipline that made Fahey a key element in the Howard government’s success.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in