A great temple of the goddess Tara can be found at Tarapith in West Bengal. But her true abode, in the view of many devotees, is not this sacred structure itself but the adjacent, eerily smoking cremation ground. There she can be glimpsed in the shadows at midnight, it is believed, drinking the blood of the goats sacrificed to her during the day. Many holy men and women live in that grisly spot too, adorned with dreadlocks, smeared with ash, and dwelling in huts decorated with lines of skulls painted crimson.

As a domestic setting this wouldn’t suit everybody. But the varieties of religious experience (to borrow the title of a celebrated work by William James) are many and extremely diverse. Tantra: enlightenment to revolution, a new exhibition at the British Museum, does a good deal to explain imagery and practices such as these, which are hard to comprehend for someone brought up to think of religion in terms of George Orwell’s ‘old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist’.

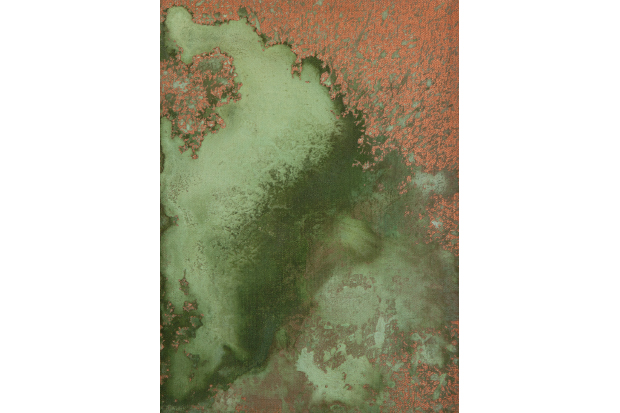

The show contains, moreover, some remarkable things. Among these is an 18th-century Tibetan Buddhist painting on silk, or thangka, depicting two deities, Chakrasamvara and Vajrayogini, intimately entwined. In the accompanying book, Imma Ramos describes the picture: Vajrayogini ‘swings one of her legs over his thigh’. He is blue, with 12 arms and a dangling garland of severed heads, miniature skulls and tiger skin. She is red and naked except for ornaments made of bone. Both have fangs and wild, red-rimmed eyes.

Altogether, as a work of art, this is quite an eyeful: the sizzling energy of a Jackson Pollock, the chromatic pizzazz of Kandinsky, plus an overall touch of psychedelic freak-out. One thing this exhibition did for me was to reveal the potential power and beauty of thangkas, which constitute an enormous chapter of art history in themselves.

But in this case, what does it all mean: the fangs and wild sex, the skull filled with foaming blood? Ramos explains the spiritual aspect like this: ‘Only the most ferocious deities can abolish the obstacles to enlightenment.’ Tantric beliefs and behaviour unleashed inner psychic forces by breaking the conventional rules, both moral and religious. They apparently originated among marginal groups of ascetics in early medieval Hindu societies who lived, like those at Tarapith today, in cremation and charnel grounds.

These ideas spread, as the exhibition illustrates, to kings, courts and across religious divisions. Eventually tantra became a strand in Buddhism as well as in the Hindu religion (hence that thangka). It’s not hard to see why this should be so. Breaking the rules is often attractive and sometimes definitely the right thing to do.

Tantrikas (the followers of tantra) not only disregarded the distinctions between purity and impurity, but also the barriers between different castes. Many of the techniques they proposed — yogic sex, for example, and the consumption of excrement, urine and dead body parts — have always come with the mystical equivalent of a ‘don’t try this at home’ warning (dangerous except under expert supervision). As with many Christian beliefs, such as the virgin birth, there is a long-standing debate between those who take it all literally and those who prefer to regard the sex and corpses as metaphors.

Nonetheless, the appeal is long-lasting. In the 19th century, Indian nationalists invoked Kali, a tantric Hindu goddess dedicated to the destruction of evil forces. To colonial Victorians, conversely, she stood for everything that was alarming and incomprehensible about the territory they were occupying.

Unsurprisingly, too, tantric attitudes and imagery were deeply attractive to the ‘all you need is love’ counterculture of the 1960s. The last section of the exhibition reveals their influence on among others Timothy Leary, prophet of mind-blowing drugs, the jazz musicians John and Alice Coltrane and the Rolling Stones’ lolling tongue logo.

This is all interesting. In artistic terms, though, the second half of the exhibition, dealing with these later developments, is distinctly inferior. The best things come earlier on — those thangkas among them. There is an array of sculptures in stone and bronze from the BM’s own collection, some of which — 1,000-year-old representations of the fearsome female deities Chamunda and Durga in particular — are spectacular feats of carving and imagination alike.

They are visualisations of the belief that the universe is charged with shakti, or primordial female creative and destructive energy, embodied in these goddesses. This, according to tantric texts, should be reflected by respecting mortal women: another highly unorthodox idea in the early middle ages and still in some places today.

These sculptures also reveal the limitations of museum-bound exhibitions such as this, because they are detached fragments of larger ensembles. An attempt to reconstruct part of a 9th-century temple through a photographic installation plus a noisy commentary is rather tacky. But the overall experience of Tantra is suitably mind-expanding. It made me want to go back to India as soon as the virus permits.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in