Slowly the world of the arts starts to take a timid step forward in plague-torn Australia.

Just as alarming new cases of Covid hit South Australia the state opera company there together with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra put on Richard Mills’ Summer of the Seventeenth Doll which is good to see even if you’re inclined to think, like the Germans, that the most viable form of contemporary opera is the musical from Porgy and Bess to West Side Story.

That incomparable man of the cinema Billy Wilder dispensed with all the songs from the musical Irma la Douce when he filmed it as a comedy with Shirley MacLaine.

But Billy Wilder was always a law unto himself. He re-jigged the plot of Witness for the Prosecution for his 1957 film with Charles Laughton and Marlene Dietrich but even Agatha Christie thought it was superior to any other film of her work.

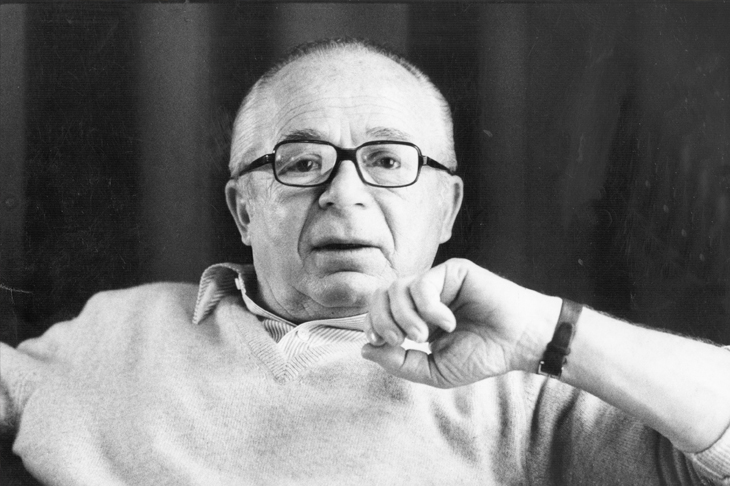

Wilder, supreme artist and creator of Sunset Boulevard and Double Indemnity, of Lost Weekend and Some Like It Hot is the subject of a new novel by Jonathan Coe, Mr Wilder and Me, which has the singular virtue of capturing the dry wit and unsparing devotion to every possible ironic perspective (without for a second losing his sincerity or his seriousness) which was the defining quality of one of the very greatest of the artistic refugees from Nazi Germany.

The deadly wisecracking of Wilder is at a higher level than anything else in Coe’s novel (very readable though it is) and it’s continuous with the rat-a-tat brilliance, razor-sharp, that you can see in the dazzling documentary interviews with Wilder on YouTube where you get bits of questions projected by one of his leading men, Jack Lemmon.

Of course, Wilder declares at one point that Jack Lemmon was not really one of nature’s leading men, he was too funny- looking. No Clark Gable, Wilder said dryly.

The moment at the climax of Some Like It Hot where Lemmon declares his true romantic status to Joe E. Brown is one of the funniest moments in the history of cinema and is one of the only moments I remember – from a lifetime ago – when I turned to my mother in the cinema where we saw it (sitting in the more expensive ‘lounge’ section of Melbourne’s old Regent) to ask her what that meant even as she was cackling her head off.

Only Wilder could have had one of the best-looking men of the post-war era, Tony Curtis, skipping about in drag and only Wilder could have said to Marilyn Monroe, when she was appalled at the black and white rushes, ‘Ah, Marilyn, you don’t need colour.’ Nor did she.

The interviews with Billy Wilder are a marvel. He says he was bored by all of Hitchcock’s fancy camera tricks, following the shadow of the very steps of some perpetrator or protagonist with maximum stealth and dazzling show. Why bother, the old Berliner says, why not let the camera simply show what it has to show without drawing attention to itself?

The interviews remind us of a thousand details like the fact that no one had ever heard of William Holden when he played the young chancer in Streetcar or that all the great Hollywood leading men backed away from the central part in Double Indemnity because they thought it would be a career killer. It was Fred MacMurray, the bumbling good-natured guy, who saved the show there and again in The Apartment with Lemmon and MacLaine.

It’s good to be reminded of how Wilder represents one kind of zenith of wit and sophistication that Hollywood never surpassed. Both the interviews and Coe’s novel – which milks them to such powerful effect – is a testament to the man who was such a supreme craftsman, and whose achievements were never separate from his shrewdness.

He loved his peers, Emeric Pressburger, who wrote the scripts for Michael Powell and Fred Zinnemann, who directed everything from High Noon to A Man For All Seasons. Eventually Wilder was left out in the cold by the Spielbergs and Coppolas. He passionately missed his collaborator I.A.L. Diamond whose great response by way of endorsement was always, ‘Why not?’

If you want to make a virtue of necessity in a strange time just sit back and watch the great films again.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in