Eighty years ago this month, the cartoonist Graham Laidler — better known as Pont — died of polio. He contracted the disease while evacuating refugees from London in his car. He was only 32. In 1940, thousands of people were dying in the war, but Pont’s death was marked by an appreciation from J.B. Priestley in the Times, and an outpouring of grief in readers’ letters to the magazine with which he had become synonymous: Punch.

Pont, the son of a successful painter and decorator, originally trained as an architect. But after he caught TB, doctors advised him to abandon his work and travel to Austria to recover. There he started submitting cartoons to Punch. After many rejections, a drawing was finally accepted in 1932. In just eight years he rose from a first-time contributor to an established regular. He became the only artist offered a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ to work exclusively for the magazine. ‘Pont of Punch’ was born.

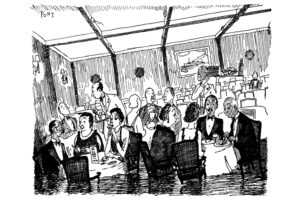

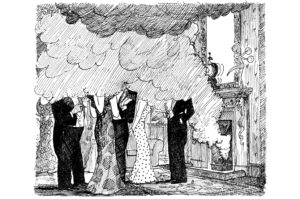

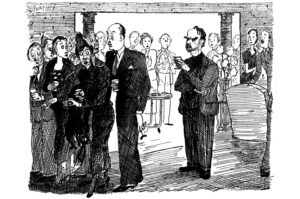

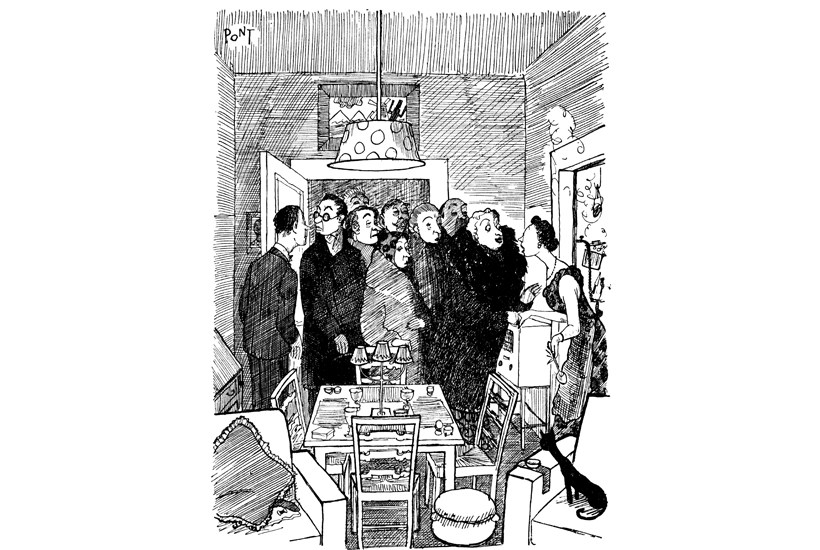

Pont was one of the all-time greats. He was an unparalleled social satirist — famous for encapsulating the quirks of human nature in his two series, The British Character and Popular Misconceptions. The former depicted tableaux crammed with detail and incident, like silent comedies. ‘The British Character. Love of keeping calm’ features the dining room of an ocean liner, with all the passengers eating dinner, oblivious to the fact that the room is listing and there is water up to the tablecloths. ‘A disinclination to sparkle’ shows a line of glum dinner guests, each perfectly observed in their lack of loquaciousness. In ‘A tendency to leave the washing up till later’, a kitchen is piled up with weeks’ worth of dirty dishes.

Popular Misconceptions allowed him to be more surreal. ‘Life in the flat above’ caricatures a family thumping up and down with a cart full of pots and pans. Even the elephant in the framed picture on the wall is jumping. ‘How to win the war’ satirises armchair strategists pontificating in club-land, listening solely to themselves. The common denominator in all Pont drawings is the absence of malice, even when depicting Nazis. Not that his drawings lacked bite — only venom.

Pont on ‘The British Character’

His observational series was so well-received at the time that Punch magazine offered him an unprecedented exclusive contract

Love of keeping calm

Partiality for open fires

A weakness for oak beams

Importance of not being intellectual

Pont’s self-effacing pseudonym derived from his architectural training: Pontifex Maximus (the greatest bridge-builder) was a family in-joke. He emulated other pseudonymous cartoonists such as Fougasse (Kenneth Bird). ‘To meet he was quiet and reserved, ready to be amused with people, or at people, or both together,’ wrote Fougasse in a preface to a 1942 collection of Pont’s work. ‘He didn’t “carry his wares about with him”, nor would it ever have given him much pleasure… to be noticed and pointed to as a “well-known humorist”.’ Pont said of himself: ‘I do not try to draw funny people. I have no sense of humour. I try very hard to draw people exactly as they are.’

It is hard to overemphasise Pont’s influence on British cartooning. A few years ago Peter Brookes, Nick Garland, Posy Simmonds, Steve Bell and I took part in a discussion of his work at the Cartoon Museum. We agreed that his observational powers were as sharp as his nib: a few lines could capture a maiden aunt, a self-important vicar or an unkempt child.

His return to Britain from Austria following the Anschluss in 1938 saw a fertile period lampooning the Phoney War — and then the absurdities of the actual conflict. A family watching the firework display of the Blitz from the top of their Anderson shelter; two sodden soldiers up to their knees in water saying: ‘I can remember laughing at pictures like this in the last war’; and his very last drawing for Punch, a matron at breakfast reading the paper, chiding her companion: ‘Must you say “Well, we’re still here” every morning?’

As a young cartoonist I was desperate to acquire a Pont original. I met his younger cousin Ann McMullan, who had written an unpublished biography of the relative she clearly worshipped as a young girl. Ann produced a suitcase containing a treasure trove of Pont originals. Reluctant to sell any, she generously gave me a small drawing that always makes me laugh — a pompous moustachioed man reading a popular magazine is asking his unseen wife: ‘I wonder what sort of people find time to read this sort of rubbish?’ It’s a question I often ask when the papers arrive, and it’s typical Pont. Acute, self-deprecating and timeless.

In the years before his death he developed a social conscience. ‘Now children,’ says a teacher to three impoverished pupils, ‘I wonder if you realise that you have inherited the largest and richest Empire the world has ever known?’ He also dabbled in more direct political cartoons — such as ‘Popular Misconceptions. Diplomacy’ in which a smug German soldier leans threateningly over an envoy.

Pont’s popularity put an end to the era of serious artists with a modicum of humour. Instead, cartoonists became serious humorists with a modicum of artistry. So important was his gifted amateurism to Punch that his editors even dissuaded him from attending art school in 1937. Following his death, a letter to the magazine from a naval officer summed up what he meant to his fans. ‘I am compelled to say how extremely sorry I am to hear of the death of Pont, your brilliant artist. I loved that man.’

‘No adjective of mine,’ the letter went on, ‘can possibly add to the penetration, subtlety and humanity of his drawing.’ These words are as true 80 years later as they were then.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in