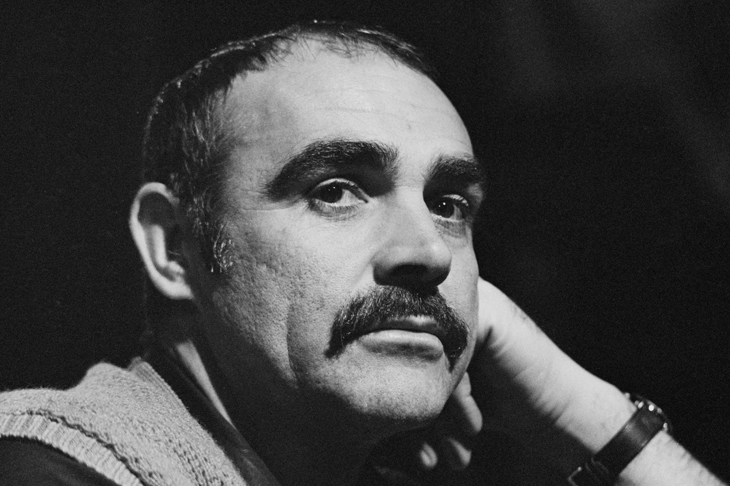

Sean Connery outlived all of them, those great British actors who came to such prominence in the early Sixties: Richard Burton by decades, Peter O’Toole by a few years, Albert Finney last year. And his fame never receded because the Bond franchise just kept keeping on. He turned himself, partly as a consequence of it and partly through sheer monolithic talent into the biggest kind of Hollywood movie star, almost archaic in his grandeur and irreducibility.

Needless to say, the stories about him as an unlettered Scots yob who had to be told how to hold a glass or see a tailor are largely nonsense, humble as his origins were. In 1960 he was in An Age of Kings, soaring in his natural born stardom in this BBC version of Shakespeare’s History Plays and it’s on record that he said that he learnt to play James Bond by playing Macbeth. I once met an old Scottish psych nurse who thrilled at the memory of seeing him on stage as the Thane and Zoe Caldwell told me she’d been his Lady Macbeth on Canadian televsion and how she had helped him quieten his nerves.

In fact Connery had an effortless authority when he did Shakespeare, he could fuse the emotion with the cadence of the line. It’s also not hard to see how he might have captured what was most lethal and dangerous in Bond by mastering that curtain of silkiness and suavity that Macbeth has to wear.

He is, after all, the most saturnine and sinister of the Bonds and if you want the quintessence of the warrior king who is also a killer Macbeth is a hell of a role to have in your kitbag.

Connery also made Marnie with Alfred Hitchcock and he’s terrific in John Huston’s film of that Kipling yarn The Man Who Would Be King. He lifts Bruce Beresford’s unhappy film of William Boyd’s A Good Man in Africa – which I watched just the other week – in a way no one else in a distinguished cast can.

One of Sean Connery’s qualities was that he could take on any national stereotype and simply absorb it into his idiom. He’s a convincing Russian in The Hunt For Red October – his co-star Sam Neill spoke with awe of him at the news of his death. He’s a convincing Arab in The Wind and the Lion. He plays William of Baskerville in the film of Eco’s medieval detective story, The Name of the Rose, in that same unmistakable Scots burr and he uses it again in his riveting performance in The Untouchables where despite the witchery of De Palma’s direction which turns the old Chicago cops and gangsters story into the grandest kind of Hollywood opera Connery upstages everyone in sight.

He upstaged Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones when he played his father. Who but Connery could have played a romantic lead opposite Catherine Zeta Jones in Entrapment when he was kicking seventy?

The only other actor who has bent the English language to his own will in this way is Russell Crowe who used his own Australian accent as his gold standard: he’s an Australian hero in Gladiator and an Australian Jack Aubrey in Master and Commander.

For Connery, as for Russell Crowe, his accent was just an aspect of his dominion.

All of which is a far cry from Roadkill which has started on the ABC and has that master comedian Hugh Laurie as a Tory cabinet minister. Anyone who had glimpsed Laurie in House is aware of what a brilliant dramatic actor he is and that impression was consolidated by the magnetism he brought to the supercrook in the TV version of le Carre’s The Night Manager.

Roadkill is by David Hare and it is entertaining tosh with Helen McCrory brilliant as a feckless PM, Patricia Hodge as a grand old newspaper proprietor and Pip Torrens (with London accent) as a tough exec. There are far too many coincidences and bizarrely young ministerial aides screwing each other but this will divert anyone who’s willing to take British politics as their fantasia.

None of the aides have the spectacular quality of Peta Credlin nor the law-unto-himself presence of the man she guns for in Deadly Decisions on Sky, Daniel Andrews. The one-hour special examines dubious goings-on in the hotel quarantine fiasco and the failure (or reluctance) of the inquiry to get to the truth of it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in