2020 will, of course, be remembered as the year in which Covid-19 was unleashed on the world. But it is one in which another menace – gender identity ideology – was put firmly in its place, in the UK at least.

Perhaps the tipping point was the deranged response to JK Rowling’s essayon sex and gender, which she published back in June. For taking issue with ‘language that calls female people ‘menstruators’ and ‘people with vulvas’,’ Rowling suffered widespread and predictable condemnation. In a subsequent article, Rowling also expressed her belief that an ethical and medical scandal is brewing:

‘I believe the time is coming when those organisations and individuals who have uncritically embraced fashionable dogma, and demonised those urging caution, will have to answer for the harm they’ve enabled’

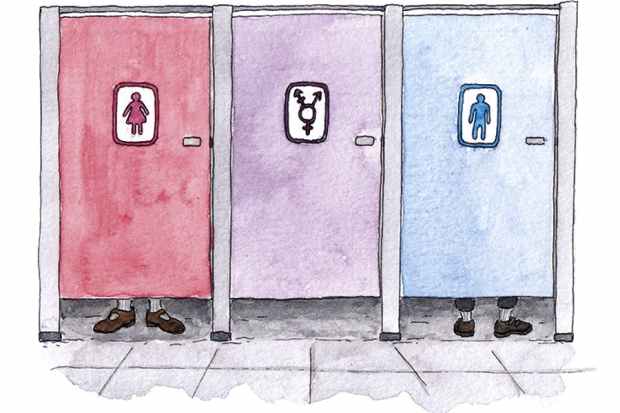

I might be transgender, but I agree with Rowling. Those of us who transitioned to escape the psychological torment of gender dysphoria had been quietly accommodated in society for decades. But this new gender identity ideology along with its ‘fashionable dogma’ demands that we abandon biology – and even common sense – when dividing society. It also requires us to segregate people rather more often, consigning individuals into new and ever more bizarre identity groups: people who were once androgynous or happy-to-stay-single are now signed up to be non-binary, asexual or given some other pangenderised label.

The resulting impact on women – many of whom are now bravely fighting a rear-guard action to protect the boundaries to their sex class – has been profound. But the effect on children has been truly devastating. Young people have been told that if they do not like the gendered expectations placed on their own sex, they can choose the other one, or neither, or a new gender. Some had already been put on a conveyor belt of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones, leading to the risk of infertility and lifelong medication.

It seemed that this menace had been unstoppable until two momentous decisions this year, both taken in the UK. First, on 22 September, Liz Truss announcedthat the Government had not been persuaded that ‘self-identification’ was a good idea. The minister for women and equalities said instead that applicants for Gender Recognition Certificates would continue to need medical evidence:

‘It is the Government’s view that the balance struck in [the Gender Recognition Act 2004] is correct, in that there are proper checks and balances in the system and also support for people who want to change their legal sex.’

But she went further and reminded organisations, many of whom have been in thrall to the emerging gender identity ideology, that the Equality Act 2010 allows them to ‘restrict access to single sex spaces on the basis of biological sex if there is a clear justification.’

Then, on 1 December, in Bell v Tavistock, the High Court ruledthat:

‘It is highly unlikely that a child aged 13 or under would be competent to give consent to the administration of puberty blockers. It is doubtful that a child aged 14 or 15 could understand and weigh the long-term risks and consequences of the administration of puberty blockers.’

How straightforward statements like these – that everyone surely once knew to be self-evident truth – became controversial, let alone generating endless commentary in the media, is testament to the progress made by the gender identity juggernaut. While the Westminster Government and High Court might be grounded in reality, parts of wider society have become entranced. Emotional responses that ricocheted across social media were then echoed by reputable organisations.

Back in September, Stonewall UK moaned about missed opportunities to make it easier for trans people to go about their daily life, citing the lack of ‘problematic repercussions’ to self-determination in Ireland. Maybe female inmates of Limerick women’s prison may think differently? Last year, the Law Society Gazette in Ireland reported that ‘a pre-operative, pre-hormone therapy, male-to-female transgender prisoner’ was being held in the prison.

Following Bell v Tavistock, Amnesty International and Libertyteamed up to declare that puberty blockers were reversible, and they were a separate treatment from cross-sex hormones; they merely allowed time for children to make decisions, was the suggestion. Yet the NHS promotes a rather different message:

‘Little is known about the long-term side effects of hormone or puberty blockers in children with gender dysphoria’.

And a recent UK study suggested that, among participants, 98 per cent of children on blockers moved onto cross-sex hormones.

In this context, World Rugby surely deserve a special mention for their decision this year to restrict female contact rugby to female people. But for all the scientific evidence cited by World Rugby, individual rugby unions thought differently. England Rugby, for example, still allow transgender women to compete with women on production of a ‘written and signed declaration’ of female gender identity and a commitment to keep serum testosterone concentration below an arbitrary level.

For some organisations, it seems that, where transgender people are concerned, they think it is better to be nice than be truthful. But in the long term, as a trans person, that does not seem to me to be conducive to building the trust and confidence that we need to be accepted in society, rather than merely tolerated. More than that, it drives me to distraction when people appear to dance on eggshells around me for fear of offending. But after the experiences of Maya Forstater and Kate Scottow, they might have just cause.

Forstater did not have her contract renewed at the Centre for Global Development after she shared her views on sex and gender on Twitter. Essentially, she thinks that transwomen (like me) are male, and we are always male because humans cannot change sex. I would agree with her – there is no point being offended by biological reality – but at her employment tribunal just before Christmas last year, a judge told her that her views were ‘not worthy of respect in a democratic society.’

Kate Scottow’s experiencewas surely worse. Scottow reportedly spent seven hours in a police cell in 2018 after being arrested for offending a transwoman. Scottow’s tweets may have been rude, but was name-calling – ‘pig in a wig’, was just one example of her tweets – and ‘misgendering’ really a matter for the criminal law? It seemed so: in February, the mum-of-two was found guilty under the Communications Act (2003), of using a public communications network to ’cause annoyance, inconvenience and anxiety’. The judge at St Albans Magistrates’ Court told her ‘we teach our children to be kind’.

But in this year of doom and gloom, there has been a happy outcome in this case: earlier this month, Scottow’s conviction was overturned on appeal at the High Court. Reason triumphed over emotion when Lord Justice Bean and Mr Justice Warby ruled that ‘free speech encompasses the right to offend, and indeed to abuse another’, adding: ‘Freedom only to speak inoffensively is not worth having.’

While nobody likes to be called names, I cannot see how the case against Scottow helped transgender people. None of us can control other people’s thoughts, but we can choose not to listen to them.

Yet while this year has given us reason to be optimistic about the gender wars playing out in Britain, let’s not forget: this is an acrimonious debate which is taking place around the world. In America, the ‘trans wars’ remain particularly nasty. And closer to home, in Scotland, self-Identification remains on the agenda.

To build the trust and confidence that leads to acceptance, transgender people like me need to be honest with society, and honest about ourselves. Trans people are human beings and we deserve to be treated equally. But this does not mean that trans people should dictate what pronouns other people use when they are referring to us. Trans people will never be equal when our rights are grounded in identity. Why? Because we end up being considered separately from everyone else. But thankfully, this year has shown that, in Britain at least, some much-needed common sense has entered this fractious debate.

Yes, 2020 has been a frankly dreadful year. But the turning tide in the trans wars is surely one good thing that has emerged in recent months.<//>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in