There is an intriguing pattern in our relationship with European integration. A Frenchman vetoed our attempt to join. A Frenchman threatens to veto our attempt to leave – or at least to leave with an agreement. General de Gaulle said we were too remote from Europe to join. Emmanuel Macron says we are too close to Europe to leave. I think de Gaulle got it right. I hope Macron doesn’t turn out to be right too, so that we end up stuck half in and half out, neither ‘at the heart of Europe’ nor ‘global Britain’.

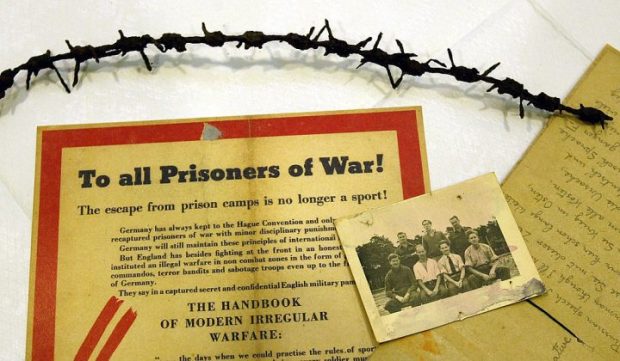

How individuals and nations react to the project of European federalism is determined not just by their calculation of what’s in it for them (though this is clearly paramount for some) but also by their notions of history. Does the European Union keep the peace in Europe? Without it would we slide back into the 1930s? Can European democracy be trusted? Does the EU make declining European nations more important?

In no European country are these historical reflections more crucial than in France, which is precisely why the French, from de Gaulle to Macron, have been so important in making and breaking our relations with Europe. This is partly due to what they do, and partly to how we react: the British and the French are uniquely touchy about each other’s words and deeds. If it was the Dutch or the Danes who were demanding our fish, I doubt they would be so tactless, or that we would be so annoyed.

Because the French have such a vivid sense of their history – both triumphs and disasters – they are suspicious neighbours. Above all, they have long felt the power of Germany, whether the old Holy Roman Empire, the Kaiser’s muscular Second Reich, Hitler’s Third, and even today’s Federal Republic. France practically invented European integration in the 1920s, believing the only way they could prevent Germany from being dangerous was by tying it into a European system. They revived the idea in the 1950s, setting up the European Coal and Steel Community to control the raw materials of war. The Germans, defeated, occupied, demoralised and divided, played along. General de Gaulle, coming to power in 1958, saw ‘Europe’ as a way of making France great again after defeat and loss of empire. He was determined that France would run it, with Germany its docile partner.

Ever since, French governments have single-mindedly followed de Gaulle’s policy of making Europe serve France. It is the only Western nation with a genuine ruling class, selected and specially trained to run the country. They colonise politics, business and the civil service. Far more than our own timid and dithering elites, they have been capable of following a long-term strategy in Europe.

Because of France’s humiliating collapse and occupation in 1940, its rulers were determined to rehabilitate themselves by asserting leadership. De Gaulle’s unshakeable conviction, which he was able to convey to his demoralised countrymen, was that France was uniquely important in the history of the Western world: ‘France cannot be France without greatness.’ As he saw it, ‘because we are no longer a great power, we must have a great policy.’ This has been an astounding political achievement. Has any country ever managed to keep a hand on the European tiller for so long – now nearly 70 years? The Sun King, Louis XIV, managed about 20. Napoleon himself only managed 10. How long can their present-day successors keep it up? We may soon find out.

Every great move towards European integration since the 1950s has been orchestrated by the French elite, with the aim of ‘political and monetary union’. The Euro was their invention to hog-tie the re-united German economy. No one – including the French electorate – was permitted to stand in the way: the vote rejecting the 2005 Constitution was ignored.

Britain, which de Gaulle wanted to keep out, was a perpetual drag on integration, but in French eyes had the role of balancing German power and providing Europe with extra economic, military and diplomatic heft. The ideal for France was for Britain to be outside the inner circle of power – that was for France and Germany alone – while being an obedient follower of the rules. In crude terms, a mug. Hence Brexit.

After our referendum, the French, encouraged by Remainer agitation, thought Brexit could be reversed, or at least nullified. It could even serve French purposes. If Britain could be kept tied to the EU economically and militarily, while being out in the political wilderness, France would gain.

From this viewpoint, Emmanuel Macron could have been the EU’s Mr Nice Guy, helping Britain to get a temptingly soft Brexit and becoming our best friend in Europe. Instead, he has been the most openly hostile EU leader. Why? Because if Brexit was made too easy, the whole EU risked disintegrating, and France’s great geopolitical achievement would be destroyed. As its Europe minister, Clément Beaune, recently told a French newspaper ‘We would be wrong to… be accommodating towards those who wish to leave… the EU is not simply a market, but also a political project and being in it or out of it are not the same thing.’ A suave way of saying that Britain must squirm. So in recent days, the French have made new demands which almost certainly prevented a trade deal from being signed last week.

Yet it would be hugely in French economic interests for the EU and UK to have a trade agreement. Britain is France’s most profitable market anywhere in the world, giving it a surplus of £12 billion a year and helping to balance its large deficit with the rest of the EU. A deal might keep its combative fishermen, its farmers and its still angry gilets jaunes from rioting and threatening Macron’s chances of re-election. But the French will not do this at what they see at the expense of their European project, however much they risk damaging themselves.

Are they mad? If so, there may be method in their madness. It’s the Franco-German power game that they are keenest on winning, and have been for 150 years, ever since the Prussians besieged Paris and forced its citizens to eat rats. The threat to France’s leadership of Europe is always Germany, and this has been increasingly clear since the introduction of the Euro. This has hoisted France on its own petard, because instead of controlling the German economy, it has given it huge benefits and increasing power. Germany is the permanent gainer from the Euro, which makes its exports cheap, whereas France (and the rest of southern Europe) lose competitiveness and accumulate ever increasing debts. The Germans regard themselves as good Europeans, because being ‘European’ wipes away their terrible history. But they are very reluctant to disburse the vast sums required to keep the Eurozone afloat and ‘level up’ the other member countries.

So France may be threatening a no deal to gain leverage over Germany. Britain is one of Germany’s most lucrative markets, so the Germans want a deal. Will France’s price be for Germany to take over a large chunk of southern Europe’s debts – including those of France – and thus move triumphantly towards federalism? The European Central Bank is lending money like crazy to southern Europe, and eventually this ends up on Germany’s tab. If over the next few days, Michel Barnier graciously makes concessions to Britain and a free trade deal is signed, it may be because the Germans have paid France off and again allowed it to steer Europe’s course. But if the French overplay their hand, their leadership of Europe will be in tatters. Macron has quarrelled with the Eastern Europeans. He is now clashing with the Spanish and Portuguese by blocking a trade treaty with South America. If he stops a deal with Britain too, there will be a lot of angry people out of pocket across the Continent, and not least in France.

What outcome is in Britain’s interests? A trade agreement that allows us to set our own economic policies and continue diversifying our trade away from the stagnant and unstable Eurozone. We must not make unreasonable concessions over fish. Even more importantly we must not sign up to one-sided legal obligations – the so called ‘level playing field’ – keeping us tied indefinitely into the EU system, with which we have an unsustainable trade deficit. In contrast, we have a surplus with the rest of the world, increasingly our main market.

Don’t get me wrong. I like the French. I admire their ruling elite for its brains, patriotism and ruthless determination. But I don’t want us to end up as their stooges.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in