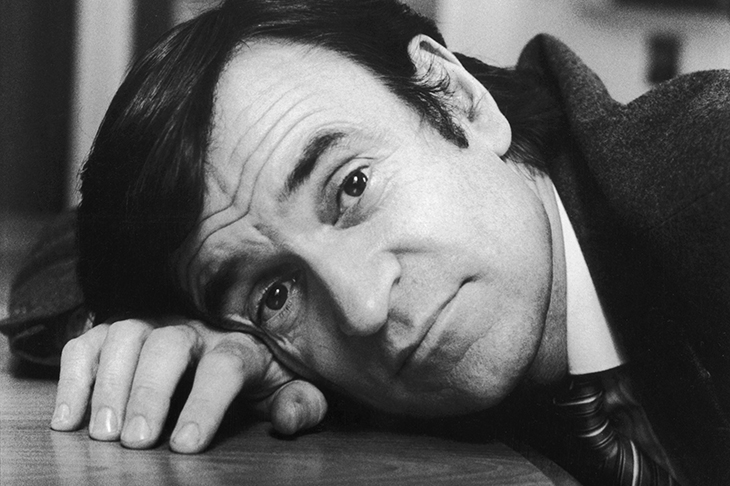

Those who best remember Dr Anthony Clare (1942-2007) for his broadcasting are firmly reminded by this biography that we didn’t know the half of him.

Its authors are Brendan Kelly, professor of psychiatry at Trinity College, Dublin and editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry and Muiris Houston, a columnist for the Medical Independent and the Irish Times. Theirs is a meticulously sourced, clearly arranged, carefully assembled account of Clare’s packed life and multiple achievements. Yet through it thrums a sense that you can only really understand him if (a) you are a psychiatrist and (b) you are Irish.

Born in Dublin, Clare was the youngest of three children, the only son. His mother was fiercely ambitious for him; his father was a solicitor. At Dublin’s Gonzaga College Anthony did well in English and arithmetic, read voraciously, started a school newspaper, acted, became a star debater and began learning the power of words, spoken and written. At 17, he chose to become a doctor rather than a lawyer, but at University College, Dublin he immediately joined the debating society. Over his six undergraduate years he won every debate trophy going, and met Jane Hogan, a fellow undergraduate reading arts. They married in 1966 and had seven children. From first to last she seems to have read and re-read him like a cherished book, comprehending its every footnote.

Kelly and Houston have arranged their book in eight sections, each covering an aspect of Clare’s life. To anyone who only knew Clare as a broadcaster it will be an eye-opener. He chose psychiatry as his field in the 1960s when it was riven by internal divisions but gaining massive external influence. The book spells out how he won arguments and achieved eminence both in his field and as a communicator, why he moved to London in 1983 and back to Dublin in 1989, and suggests why he fell into final depression. In the middle is a vivid account of how he became a figure that the general public, beyond medics and academics, came to know.

The programme In the Psychiatrist’s Chair (1982-2001) was not the first time audiences had heard Clare. By then he was already a regular broadcaster on many shows, among them Radio 4’s long-running Saturday evening conversation Stop the Week, created by Michael Ember and chaired by Robert Robinson. Clare and Ember bonded. Together they devised the programme that would make their names. Kelly and Houston catch its essence:

The format of In the Psychiatrist’s Chairwas that Clare would interview guests in considerable depth and without haste, in an effort to explore their childhoods, self-image and current motivations… In pursuing these themes over the following years Clare was unfailingly courteous and supportive with his guests, listening for the most part, rather than interrogating. He was also endlessly curious, often robust and, at times, remarkably and controversially persistent.

Claire Rayner, a guest in 1988, knew what that meant. He had her in tears, on and off air, and she never accepted why he felt it necessary. Still, the programme made him a name way beyond Radio 4, attracting famous guests including those who normally dodge personal publicity (Anthony Hopkins) and one (Jimmy Savile) who prided himself on never giving anything away. Ann Widdecombe thought she’d got the better of Clare. The audience thought not. Most occupiers of the chair felt honoured to be asked. At a time when radio was regarded as television’s poor relation, the programme had the winning combination: avid audiences, news value and chic.

Yet during its 19 years Clare was living several parallel professional lives, running hospitals, writing copiously, speaking, travelling, campaigning and doing so many shows for different broadcasters the lists run over several pages. His work rate was frantic. As time passed he grew selective. His wife remembers:

He had no time for committees, unless he was chairing them, or conferences — he only went to those if he was a speaker, and was at his best in intense but relatively short-lived collaborations, except for his long-lived one with Michael Ember.

On his return to live in Ireland Clare chose to work in the private rather than public health sector, a decision these authors judge mistaken. He stood for the Senate but didn’t win. It hit him hard, though the work rate and the travel didn’t flag. His son Peter recalls that ‘in later life he became depressed, withdrawn, harried’.

Clare died in Paris, of a heart attack, in October 2007. He and Jane were on their way to see their latest grandchild, and he was two months from retirement. This book is the first assessment of a remarkable life and a brilliant career. It is thorough, referenced and footnoted to the highest standard. Yet under its chapters keens a Celtic melancholy, mourning a great man while resenting the foreigners who made him famous.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in