Late last year saw publication of another indigenous report, thousands more words about challenges facing these troubled communities. The Australian Human Rights Commission’s Women’s Voices report contained a heavy focus on protecting women from indigenous violence, claiming this was critical for healing the intergenerational trauma afflicting so much of Aboriginal society.

It makes sense to highlight the alarming levels of indigenous domestic assault, with so many women and children victims of male violence. But the glaring omission in all such discussions is the vital fact that many indigenous children are cowering not from their fathers but from violent mothers. Hiding from drunken mothers, or women unhinged by mental illness.

In such dysfunctional Aboriginal families, father-absence is common – it’s rare for men to remain actively involved in children-rearing. The result is that everyday exposure of these children to abusive lone mothers is a major contributor to that cycle of violence that locks in intergenerational trauma.

Yet it is very rare to see any published statistics about indigenous women’s violence. Despite the numerous reports drawing attention to violence in these communities, data on indigenous women is hardly ever included.

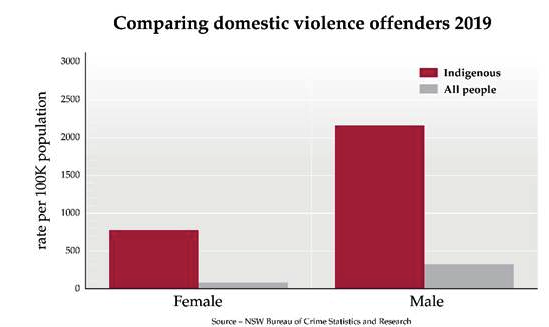

The startling fact is Aboriginal women are actually more than twice as violent as men in general in Australia. Just think about the billions of dollars governments across the country spend demonizing ordinary men as threats to women’s safety, and not one word about this other key group of perpetrators.

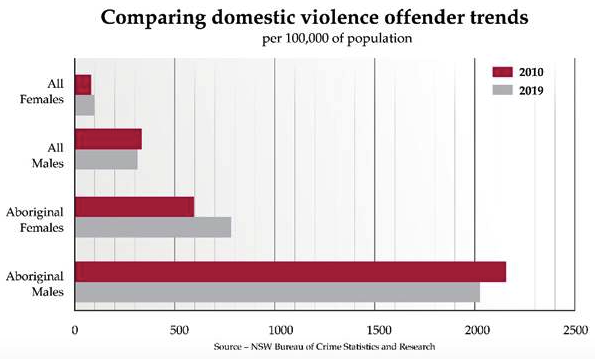

It took a special request to the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics (BOSCAR) to dig out this vital statistic. The BOSCAR data shows that whilst overall rates for male perpetrators of domestic assault are dropping, women’s rates are increasing, with indigenous women showing the most dramatic rise. They are now eight times more likely to perpetrate domestic assault than women in general (the full statistics are available here):

So why do we never hear about this? The answer is simple. The powerful grip of identity politics ensures Aboriginal women have a double dose of protection from public scrutiny. They are indigenous – tick. And also, women – tick. Hence, they are untouchable. And all the abuse in indigenous communities is sheeted home to men.

That’s a totally unacceptable state of affairs for Phillip Bligh, an indigenous leader from the Central Coast of NSW. Bligh has spent over 30 years working in indigenous communities and schools and acting as a consultant for governments and other key organizations.

Three years ago, Bligh was commissioned by White Ribbon Australia (WRA) to review a training manual aimed at “engaging men to prevent gender–based violence” in indigenous communities. Concerned about the high levels of violence in Aboriginal society, Bligh was keen to ensure the manual was culturally appropriate.

He was shocked by the biased, anti-male approach taken by WRA, who presented him with a trainer’s manual focussed entirely on men violence against women. Bligh: “It is widely accepted by indigenous people that there is considerable female violence in our communities too. For decades I have been talking about violence with both indigenous males and females. I’ve attended conferences and Aboriginal men’s camps, participated in community meetings where we’ve discussed the problem. The story was almost always the same: both genders are capable of committing violence and both endure high levels of pain and suffering from emotional and physical abuse in their homes.”

Having taken on the consultancy, Bligh spent many months speaking to indigenous people from across the country, checking out whether others agreed with the impressions he had gained through his previous work. He discovered many are concerned that the narrative about indigenous violence is being framed with men as the sole perpetrators, totally ignoring the men who are victims of female abuse.

“A respected Elder from the Central Coast told me he was treated badly by Wyong Police when he reported physical abuse by his female partner. ‘Are you a man or a mouse?’ the police sneered.” The man then reached out to a Domestic Violence Helpline where the helpline worker refused to listen to his story, telling him they weren’t interested because he was male.

“The idea that men are the sole perpetrators of violence in our society and women are always the victims runs deep and the prejudice in the narrative is reflected in the available services,” comments Bligh mentioning a female police officer who specifically asked him if he could do something for the indigenous male victims she encountered. “Police have told me that men needing help are left out of the equation altogether.”

Even more disturbing was Bligh’s discovery about how easy it was for accusations of domestic violence to be used against men. Indigenous women making accusations of violence by men were invariably believed even in cases where the women were the real abusers. He came across a case involving a young indigenous man charged by Gosford Police for “striking” his mother. The police accepted her story even though there were no physical markings on her. The young man was charged with seven violations from “intentionally” breaking or damaging furniture to “stalking and intimidation.”

Before the matter ended up in court, most of the charges were dropped due to evidence emerging of a long history of abuse of the boy by his mother. “The case was so stressful for him that he was suicidal. Like most young indigenous men, he had no access to legal help. But even when it turned out she was making things up, she was never charged.”

“The more I discussed the issue with people in my community, the more troubled I became by the way domestic violence is incorrectly formulated in our country, particularly by the feminist movement, and how widespread their erroneous narrative is in governments, media, judiciary and government agencies like police,” says Bligh who is specifically concerned about the harmful effects this discourse is having on his own community.

That’s why he reached out to me, keen to speak out publicly about this distorted narrative. He attempted to recruit other indigenous leaders to join the discussion we filmed for a YouTube video I made with him addressing these issues. “Many agreed in private but weren’t prepared to go public. It’s a risk for a man to enter this debate. But I believe we need to have a mature and sensible discussion about what is going on.”

Last year the White Ribbon Association was declared bankrupt and ceased operation, but now it is back, spreading its message across the country, sadly including through our school system. Phillip Bligh is particularly concerned that White Ribbon is back in schools shaming boys by having them acknowledge their “toxic masculinity.”

“Boys are singled out and made to take the White Ribbon oath in front of their classmates. For a young indigenous man this may be interpreted as a stain on his character. At a time when our boys are wrestling with identity and self-esteem issues, when they are trying to make sense of the world through Aboriginal eyes and understand their place in it, they’re told by organisations like WRA that they’re flawed human beings, monsters–in–waiting, and must apologise in advance for their impending malevolent behaviour.”

Bligh talks about growing up in a small town near Bourke, where boys defined their masculinity by their physicality. “We were very physical, we all played a lot of sport, rugby league, boxing, tennis. Now the feminist push is to stop boys from being physical because that’s toxic masculinity, a breeding ground for patriarchal attitudes and male dominance. It is very damaging to Aboriginal young men being discouraged from the active play that helps them learn to control their physical strength.”

But even now, there are many Aboriginal communities with well-functioning families explains Bligh, taking issue with the feminist assumption parroted by WRA that domestic violence is evenly spread across society. It’s well documented that there are some Aboriginal communities, particularly in outback Australia, showing far higher levels of mental health problems, suicide, drug and alcohol usage and it is here that domestic violence levels go sky high. BOSCAR has a revealing map on their website comparing rates of domestic violence across the State – showing outback Australia with the highest levels of risk. NSW’s most troubled towns are Coonamble and Walgett where about a third of the population is indigenous.

So domestic violence is far from uniform across these diverse communities – which means it is nonsensical to assume toxic masculinity and patriarchal attitudes are the underlying cause of the problem. And how does feminist theory explain the high levels of violence in indigenous women? Oh, that’s easy. The group is simply eliminated from the discussion.

Bligh’s major concern is that the current distorted discourse denies the real cause of domestic violence in his community, the complex mix of mental health problems and drug and alcohol abuse which he argues are, at least in part, attributable to the ongoing psychological effects of colonisation. And then there’s the critical impact on children growing up in violent households. “In these homes there’s a lot of push and shove, argie–bargie between the parents. Two-way violence – that’s what the children witness,” says Bligh.

Contrary to the feminist narrative, that is exactly what children are witnessing across society. Back in 2001 the Young People and Domestic violence study found that 23 percent of 5,000 children between 12-20 were aware of domestic violence against their mothers or step-mothers but 22 percent had witnessed violence against their fathers or stepfathers by their mothers or stepmothers. Two-way violence is the norm emerging from the bulk of international domestic violence studies.

But that study was buried, just like the statistics on indigenous women’s violence. It remains to be seen whether Phillip Bligh’s brave move will make any impact on the dialogue around this carefully controlled, explosive issue.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in