The government’s most important economic policy is its vaccination programme. The speed at which people are immunised will determine when — and how quickly — the economy can reopen. If all goes to plan, Britain will be the first country in Europe to get rid of restrictions and start the job of social repair.

Three factors give grounds for hope. First, there is remarkably little ‘anti-vax’ sentiment in the UK. More than 70 per cent of the population ‘would definitely get’ a Covid vaccine if it were made available to them this week. In Germany, it’s just 41 per cent; in France, 30 per cent. The willingness of the British to have the jab means that there will be no major problems with take-up. Second, the UK has a fridge-temperature vaccine — the Oxford-AstraZeneca one — approved by the regulator. This considerably eases the logistical challenges of distribution. Finally, we have a health service well suited to a mass immunisation programme.

Despite these advantages, ministers are nervous about whether the government can pull the vaccination programme off. ‘This is the real test because the British state has catastrophically failed so far,’ one Secretary of State tells me. (Tories often talk about the failures of ‘the state’ rather than their government.) But the initial signs are that the vaccine rollout is going better than the procurement of PPE last spring or the launch of the test-and-trace system. The daily publication of vaccination figures also brings huge public and media scrutiny of the programme, which should improve its performance.

Boris Johnson repeatedly got into trouble during the pandemic for making overly hopeful predictions, so now he is quick to downplay the prospect of a ‘big bang’ easing of restrictions. But if the government can hit its target of vaccinating the 13.5 million most vulnerable people by the middle of next month, we may see a return to the old tier system soon. Optimistic ministers think that most of England should be in something akin to Tier 2 in March. Under the old tier rules, schools and shops were open and pubs and restaurants could serve alcohol with substantial meals, but no indoor household mixing was allowed. Other more cautious figures think there is unlikely to be much easing before April.

The big question is: when will proper normality return? The view in government is that even as the death numbers fall, the pressure on hospitals lags behind, and so some restrictions will have to remain in place.

But by the end of spring, ministers believe almost everyone likely to die from Covid-19 will have been vaccinated and enough time will have elapsed for the jab to take effect. The government will then aim to immunise the entire adult population as fast as possible. The fear in Whitehall is that at the point that a large portion of the population is vaccinated but Covid not eliminated, there is a risk that the virus will mutate in such a way as to evade the vaccine. While there is confidence that the vaccines could be rapidly tweaked, the whole process would have to start again, delaying everything and dealing another huge blow to the economy.

Even when restrictions lift domestically, there may continue to be rules on those entering from abroad. The view is that testing and tighter procedures at the border will be needed to protect the UK from the danger of any vaccine–resistant strain. One figure in government tells me that ‘the advantage the vaccine has given us is so huge that we have to protect that’. The government is particularly interested in how Australia has used tough border measures to keep Covid out. There is a feeling that Australia is a ‘parallel democracy’ and so the restrictions used there could be replicable here.

This Australian-style system — whereby entry is refused except to residents and those with an exemption, and quarantine must take place in a state-approved facility — would be devastating for business travel and tourism. But there is a growing sense in Westminster that this might be a price worth paying to protect the domestic economy from potential new strains of Covid until other countries have caught up with their vaccination programmes — though even advocates of the strictest measures accept that hauliers would have to be exempt from quarantine and allowed in (if they had a negative test) to keep trade flowing. Others are sceptical, and think the Australian approach is possible only because of its geographical isolation. But the fact that such debates are taking place is a reminder that a return to true normality will take considerable time.

The Covid crisis has been so all–consuming that it is tempting to imagine that politics could enter a period of calm once it is over. But even aside from the coming Scottish parliament elections in May — and the likelihood of demands for a new independence referendum following an SNP victory — there is plenty going on. If it were not for Covid there would be a heated debate, for example, about what steps the UK should take now that it has the power to abolish EU regulations.

Nearly all such regulations are still in force, and Downing Street is keen to do a spring clean. Abolishing some could provide early examples of the advantages of Brexit (as we saw with the removal of VAT on tampons). But the view among departments is that the bigger opportunities come from breaking away from the flow of new EU regulations. In other words, the new rules that will apply in the single market but that the UK is now under no obligation to adopt.

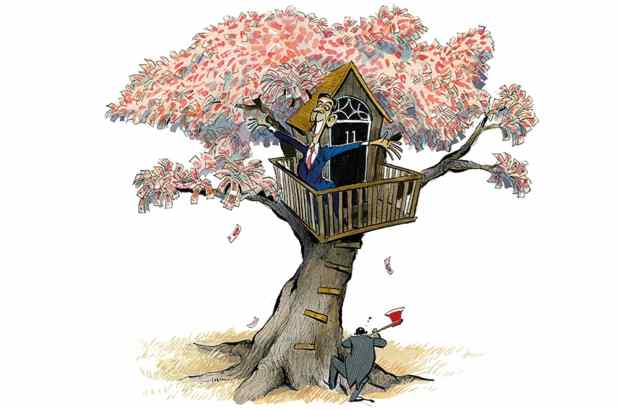

Then there is the question of how big the state should be after Covid. The pandemic, and the ways in which the government has shut down economic activity, led to a massive expansion in spending. The staggering sums spent — £12.5 billion on PPE, £22 billion on test and trace — have created a sense that even sums in the billions are not that large. The Bank of England printed money, the government borrowed — and then spent it. And so far, the sky has not fallen in. You can see this logic at play in the debate over whether to extend the £20 uplift in universal credit which would cost £6 billion.

The pandemic is often compared to a war. The two world wars led to a permanent expansion in the size and power of the state. Covid, involving a similar collective national effort, may well end up doing the same.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in