Even with its 27 amendments, the US Constitution is only 7,591 words. I keep it beside me, and find in it — as Sir Walter Elliot found in the Baronetage — ‘occupation for an idle hour, and consolation in a distressed one’. The final part of Section 3 of Article 1 is relevant in this distressed week: ‘Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to Removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of Honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.’ To use, after Donald Trump’s departure, a device designed to remove a president seems strange. Surely there are two important things to reconcile — to make sure he cannot hold office again; and to find ways of convincing more than 70 million Trump voters that the process used is just.

Twice last week, almost unreported, electricity generators were able to command a mad price. On Thursday evening, it reached £1,400 per megawatt hour; on Friday, £4,000. The typical price is £40 per megawatt hour, so the shortage of power on Friday multiplied the price 100 times. The changing pattern is ominous. There were no price spikes above £1,000 before 2016. Until last week, there had been ten since that date, so two such events in two days is quite something. The lucky recipient of the top price was West Burton power station in Lincolnshire. Things could get worse in the autumn, as we leave wicked old fossil fuels behind. We may begin to shiver when the wind fails to blow.

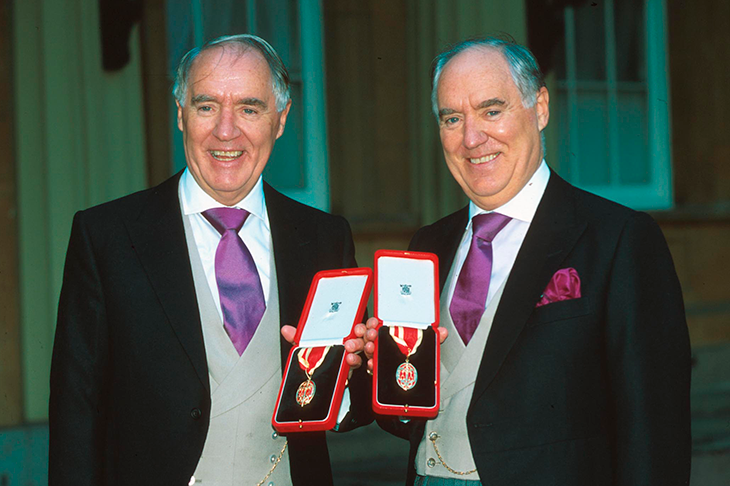

I am sorry that the rest of this column takes obituary form. Sir David Barclay, who has just died, was co-proprietor (with his twin, Sir Frederick) of The Spectator since July 2004, a longer reign than any since the early 1950s. He was also the least visible. He never came to the office or met the editor. He was so averse to publicity that I feel slightly guilty writing even this, but his proprietorial distance is worth saluting. On the one occasion I met him, I at first failed to recognise him. I quite often talked to Sir David on the telephone, however, mainly in relation to my biography of Margaret Thatcher. He and Sir Frederick admired her, and made sure she could afford to spend the last months of her life in a suite at the Ritz, which they then owned. She died there, and the brothers installed a commemorative bust. When she heard in late 2003 that the Barclays wanted to buy the Telegraph Group (which included The Spectator), she said to me: ‘When the Barclays decide they want something, they see it through to the end.’ David Barclay made a great fortune, founded on property. It was a source of pride to him that he started life in a two-bedroom, top-floor flat measuring 700 square feet in Sinclair Road, Shepherd’s Bush, and ended up in his own castle measuring 74,500 square feet. Early on in the Barclays’ ownership, I wrote a column in the Telegraph attacking suggestions that a law should prevent insults of the prophet Mohammed, even if these included calling him a paedophile. I received veiled death threats. Told I would get a call from Sir David, I feared a ticking off for causing trouble. In fact, he rang to offer me private security. I declined, but was touched.

Katharine Whitehorn, who has also died, first made her name as a writer in this paper. She began a column called Roundabout in 1959. ‘I knew exactly what I wanted to do with it,’ she later wrote. ‘It was to start with a report on something — a book, an event, a trend — and then make a thoughtful, or ribald, point from it, so that it was not just reportage.’ Her stance, rare in the press of the time, was that of a modern woman — funny, tolerant, sharp but rarely angry. Her first by-lined Spectator column is set in the girls’ school uniform section of a department store. She complains about the extreme dreariness of the clothes. The piece ends: ‘“But they do look so nice when you see them all together in their navy tunics,” the girls’ department head insisted.”’

‘They,’ Whitehorn signs off, ‘Neither she nor anyone I spoke to said she.’

In the following year, she published the bestselling book Cooking in a Bedsitter. Part 1, ‘Cooking to stay alive’, is much longer than part 2, ‘Cooking to impress’, but her skill was to help young women combine necessity and pleasure with an almost complete lack of room. Its spirit is just right for young people now working from home in tiny flat-shares during Covid. The technology has changed, of course. The entry on milk in the book’s ‘Beginner’s Index’ assumes you don’t have a fridge: ‘To stop milk going off in really hot weather, scald it.’ One of the modernities she advocated was the casserole, introduced thus: ‘A French politician representing a somewhat backward district in Africa was found to have been eaten by his constituents. The journalist who discovered this used the phrase: “Je crois qu’il a passé par la casserole” (I think he ended up in a casserole). Clearly the Africans knew what they were about. For making a meal out of tough and intractable material, the casserole has no rival.’

In the same week as Katharine Whitehorn died Albert Roux, the king of the other end of cooking. In my Note last week about Edward Cazalet’s memoirs, I did not have space to mention that Roux’s first job in England (in 1959) was as chef to the Cazalets at Fairlawne. Since it was a racing yard, he devised slim dishes, including what Edward describes as ‘the perfect thinning meal — hot consommé, a lamb cutlet and mountains of spinach, followed by a sort of puree of fresh oranges’. Roux took to riding out regularly with the Fairlawne string. Weekends were different, and dishes like soufflé Suissesse (Roux’s recipe is online, I notice), sole mazai, pot-au-feu ‘and other mouthfuls of joy, such as foie gras on artichokes and roast sea bass with a special meat juice cause’ helped persuade guests as various as the Queen Mother, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, Christopher Soames, Anthony Powell and Noel Coward that Fairlawne was the place to be. After eight years, Roux left to found Le Gavroche.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in