In March last year, the world made an interesting discovery. We found that a high proportion of knowledge-work could be performed remotely. Significantly, this came as a surprise to everyone. It should be a source of mild shame that, for all their talk of innovation, very few companies or institutions had experimented with this possibility beforehand.

Given that this technology might help solve the housing shortage, geographical inequality, intergenerational wealth inequality, the transport crisis, the pensions crisis, the environmental crisis and almost everything else people worry about, it seems odd that it attracted so little consideration until a pandemic forced our hand.

Now, at the risk of sounding smug, I was an outlier here. Back in 2018 I instigated ‘Zoom Fridays’ among my colleagues to find out what worked and what didn’t. I don’t think this was prescience on my part; instead, I was an outlier for several other reasons.

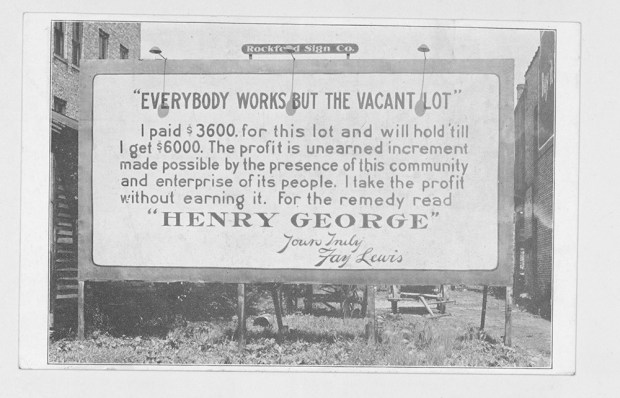

Firstly, I am a bit of a Georgist. Essentially, Georgists believe that those who extract income through the control of land and location are less deserving of their gains than those who earn their money doing something constructive or inventive. This alerted me to the fact that, of every pound we pay our younger London staff, barely 25p is left as discretionary income once tax, accommodation and transportation costs have been hived off. Add other overheads and we must earn about £7 in revenue to pay a London employee a discretionary quid. This seems wasteful.

From this perspective, it is far more cost-efficient to reward employees if they do not subsist in a state of indentured servitude paying a third of their pre-tax salary in rent to some undeserving git who decades ago fluked into buying a two-bedroom Clapham flat for £190,000. If I pay a London-dwelling employee 10 per cent extra per year, they might be able to afford a larger airing cupboard by 2030. If I pay the same to my colleague Mike, who now works from Sheffield, he’ll end up living in the Yorkshire equivalent of the Hefner mansion.

Yet the biggest counter-cultural belief I hold is that our obsession with urbanism and high-density living rests on outdated assumptions which are entrenched in government policy and planning. Buy-to-let and investor money has flooded the market with two-bedroom flats which are perfect for renting to a flatshare but hopeless for long-term family occupation. Noticeably, all futurist debate revolves around ‘smart cities’: never ‘smart suburbs’ or ‘smart towns’.

I am not denigrating handsome smaller cities such as Newcastle, Cardiff or Liverpool which are of sane scale and offer a variety of just-about-affordable accommodation. Nor am I recommending that you move to the Outer Hebrides. But the assumption that progress necessitates stacking tens of millions of people in high-rise hutches flies in the face of evidence showing such living conditions increase the odds of depression, psychosis and a general loss of happiness. Paradise is earning a London salary while living in a market town.

Our urbanist obsession arises partly from the fact that, in the realm of architecture and urban planning, the Nazis kind of won the second world war. It is also driven by delusional notions about population growth and the supposed shortage of land. But it misses something else: digital networks, unlike hub-and-spoke road, rail and airline networks, deliver their benefits equally to everyone connected to them, regardless of their location. Amazon is no better in London than in Aberystwyth. The more life is conducted digitally, the less location matters, and the less need there is for agglomeration of people.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in