We already know much of what will be in Rishi Sunak’s Budget next week. Another £30bn for Covid-relief measures: furlough scheme into the summer, stamp duty holiday and the uplift in universal credit (which is also expected to be time-limited, despite pressure from the opposition to make a permanent adjustment).

But this year’s spending splurges are becoming a footnote in a Budget dominated by the prospect of tax rises, for which the Chancellor is already receiving backlash from the left and right. Rumours of a corporation tax hike, circling for a week now, have not been denied. There’s also talk of capital gains tax coming under the Treasury’s spotlight, with some saying that Sunak aims to align it with income tax.

If this happens, the Tories would be overhauling one of their biggest economic successes. The fall of the corporation tax rate over the past decade is a success story for those who argue that lower taxes can mean higher revenue. George Osborne announced major rate cuts in 2010 – from 28 per cent – and it is now at 19 per cent. Over that time the revenue it raised rose from £34bn to roughly £60bn. And guess what? Tax cuts also saw them hire more people: a jobs miracle that took unemployment to 40 year low.

It was a major point of criticism during the 2019 general election that the Labour party kept pledging to fund every spending fantasy through a rise in corporation tax; not simply because the numbers never added up, but because the premise itself had become a flawed one: evidence wasn’t on the side that claimed a higher tax rate would directly result in more cash flowing into the Treasury. Surely the last decade busted that myth?

For Sunak to reverse this tax rate trend, possibly raising it to 25 per cent, suggests desperate times indeed: a Treasury trying to find short-term options to get in a bit more revenue, even if in the medium term it is by no means the ideal policy. And perhaps Sunak himself knows that, like the 50p tax, it runs the risk of raising very little at all.

But it would do harm. Let’s think ‘global Britain.’ As the Centre for Policy Studies’ Tom Clougherty revealed alongside the Tax Foundation, the UK already fares poorly when it comes to international tax competitiveness metrics, ranking 22nd out of 36 OECD countries last year, due to its ‘ungenerous approach to business investment allowances.’ The CPS found a hike of the tax rate to 24 per cent would plummet the UK’s overall standing to 30th out of 36: hardly something for an outward-looking Brexited Britain to boast about.

In a move to distract from the grim reality of tax rises and get back to the giveaways this weekend, the Treasury announced last night its policy plan to help get more young people on the housing ladder: a return of 95 per cent mortgages, guaranteed by the government, to help first-time buyers access a home for roughly half the down payment. The scheme is a rehash of Help to Buy, launched in 2013 by David Cameron’s coalition.

When assessing Help to Buy in 2019, the National Audit Office found that roughly three-fifths of people who had used the scheme could have afforded to buy a home and secure a mortgage without government assistance: in other words, Help to Buy worked as a hand-out to relatively well-off young people who were already in a position to buy a home. Helping the wealthy young to buy a flat in Soho wasn’t exactly progressive. Yes it did help many thousands of others – but how much cheaper would their house have been if Help to Buy did not exist?

The scheme was found to have inflated house prices – not a terribly surprising outcome, if you create more demand for homes without increasing supply – which simply worked to further price people on lower incomes out of the market, putting the dream of homeownership even further out of reach.

In the best-case scenario, these kind of schemes top up wealthier people and distort the housing market further; in the worst scenario, they enables people who can’t really afford the house in normal circumstances to sink themselves into serious debt.

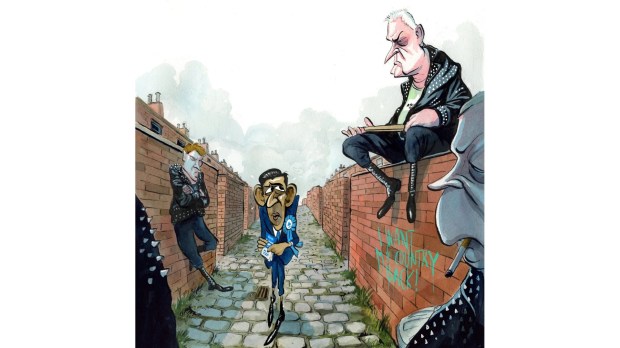

Some would frame the Chancellor’s tax hikes and giveaways as night and day – but fundamentally the two are linked. Together they start to paint a picture of a government between a rock and a hard place.

In truth, Sunak is a tethered Chancellor with few options open to him. The 2019 Tory manifesto ruled out increases in income tax. The Prime Minister has ruled out spending cuts and Cameroonian forms of austerity. There is only so much Sunak can do, especially with the economy still locked down for months to come. On housing, many in the Conservative party have acknowledged the serious harms created by lack of housing supply – but this still has not translated more broadly into the political gumption needed to take on the NIMBY wing of the party.

Some of this resistance to a more bold approach is driven by circumstance, some of it is political nerves: but misguided tax hikes or help to buy policies are unlikely to solve the problems they seek to address.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in