That Craig Kelly does not believe he can speak “frankly” and “fearlessly” on important public policy matters such as the government’s health response to the coronavirus from the government benches should concern everyone who values freedom and democracy.

Rather than defending liberal democratic values such as freedom of speech and open debate, Morrison saw advantage in telling Parliament earlier this month that Kelly’s views “do not align with my views, or the views of the advice that has been provided to me by the Chief Health Officer.”

The people of Kelly’s electorate in Hughes could be excused for thinking that Kelly was elected to represent their views, rather than those of a representative of another electorate or, less so even, of an unelected bureaucrat.

Kelly’s constituents, for their part, appear more than satisfied with the representation they have received from Kelly, rewarding the Liberals with a 60 per cent two-party preferred vote at the 2019 election.

But, at least for the remainder of this term of parliament, Kelly will continue to represent the people of Hughes on the crossbench as an Independent, rather than as a member of the Liberal party.

In a statement regarding his resignation from the Liberal party, Kelly said “if I’m to continue to act in line with my conscience and principles, and the oath I took on becoming a member of Parliament, and to speak fearlessly and faithfully represent my constituents, I have no alternative other than to resign as a member of the Liberal party.”

Whether one agrees or disagrees with Kelly’s views on treatments for the coronavirus is beside the point. It is integral to the proper functioning of democracy that there can be a free and open discussion of ideas.

If anything, Australians deserve to have more members of parliament, from across the political spectrum, speaking out on important issues rather than glibly toeing their party’s line.

It is often remarked that Australia’s system of lawmaking is a unique hybrid of Washington and Westminster, so-called ‘Washminster’. But one key feature of both the US and UK systems that did not migrate to Australia is the common practice of backbenchers having substantial license to freely voice their views on the issue of the day, even if it goes against official party or government policy.

Political parties in Australia typically rigorously enforce adherence to party policy, and backbenchers are no less expected to demonstrate support for those policies in their public comments and parliamentary voting.

This is reinforced by the process of candidate selection: members of parliament in the major political parties typically owe their preselection as candidates to the machinations of the political party, usually in coordination with the leadership of the party in parliament.

As Kelly has just learned, there is a great deal of risk for a backbench parliamentarian to develop a unique policy programme tailored to their electorate, when there is a threat from party leaders to deny opportunities for elevation to the frontbench or to deny preselection altogether.

Since the party leadership can impose strong discipline on backbench parliamentarians, and determine the composition of the executive, the parliament is thus rendered a tool of the executive. The effect is to diminish debate and dampen the spread of ideas.

This is one of the reasons why, for example, having more members of parliament and a bigger backbench can allow for more divergent voices: the bigger the backbench, the harder it is for party leadership to impose conformity and the weaker political whipping becomes.

Kelly is perhaps the closest Australia has to an Alexandria-Ocasio Cortez, a Matt Gaetz (the outspoken and articulate congressman representing Florida) in the US, or a Jacob Rees-Mogg in the UK; individuals from across the spectrum who enliven debate through their contributions which often go against their own party’s establishment.

Maiden speeches aside, it is difficult to remember the last time any member of parliament had anything interesting, captivating, or informative to add beyond their party’s official talking points for the day. And we are poorer for it as a nation.

Growing censorship on social media and amongst big business and sporting codes has been a concerning feature of Australia’s social landscape over the past decade.

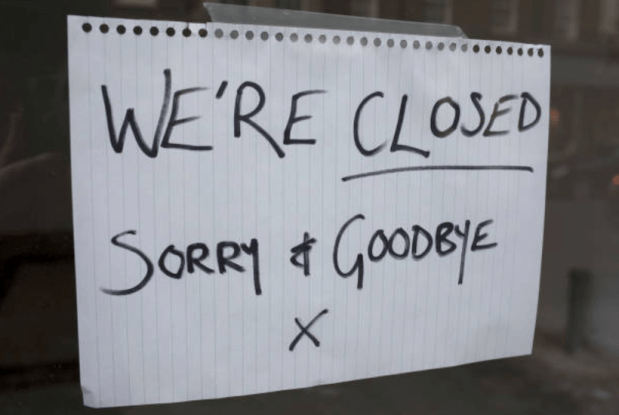

But now cancel culture has now come to the government’s backbenches.

Daniel Wild is the Director of Research at the Institute of Public Affairs. Join as a member at www.ipa.org.au.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in