It’s my new lockdown ritual. Switch on the telly, cue up the menu and scroll down to where the vintage movies gather — Film 4, or the excellent Talking Pictures TV. Then search through their early-hours offerings, and press ‘record’ more or less at random. Gainsborough costume flicks; Rattigan adaptations; anything with John Mills in a submarine — it’s all good. Then, next day, trawl through the catch to see what’s surfaced, and who wrote the music. On a good night you might get Vaughan Williams in 49th Parallel, Richard Rodney Bennett in Billy Liar or — bewilderingly — the fire-breathing serialist Elisabeth Lutyens, keeping herself in cigarettes and brandy with scores for The Skull or Dr Terror’s House of Horror. It’s all there in black and white: an alternative history of British music, piped straight to your sofa.

What that history might have looked like if postwar theatre had paid as well as cinema — and, in honesty, if Britten and Tippett hadn’t been quite so good — is suggested by two recent opera recordings. William Alwyn’s Miss Julie is not new to the catalogue: it was recorded in 1977 before vanishing from view until this 2019 concert performance. Malcolm Arnold has had an altogether happier posthumous experience, fêted in his (and, by coincidence, Alwyn’s) home town of Northampton, and increasingly respected as a symphonist. But the idea of Arnold as an opera composer comes as a genuine surprise. Even his biographers barely mention his 1952 TV opera The Dancing Master, which the BBC rejected as ‘too bawdy for family audiences’. Neither work has ever been staged.

Arnold is the most obvious winner here: at 75 minutes, The Dancing Master might be the most nimble-witted British opera buffa between The Gondoliers and Walton’s The Bear. Comedy came naturally to Arnold, and this adaptation of Wycherley’s Restoration farce is proof that the composer who gave the world A Grand, Grand Overture (that’s the one in which the orchestra accompanies a quartet of vacuum cleaners) and scored The Belles of St Trinians could do elegance, even sensuality, as well as chortling bassoons. It begins with a snort for full orchestra, and the music bustles fast and bright: lilting serenades, cartoon pratfalls and tango rhythms. The conductor, John Andrews, is a comic-opera man to his fingertips, and both the cast and the BBC Concert Orchestra sound as though they’re on their toes and loving it.

Alwyn is a slightly thornier case. After a film career that included The Winslow Boy and Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out, he spent the proceeds composing symphonies (a career move echoed more recently by Christopher Gunning, an arresting contemporary symphonist still best known for the music to ITV’s Poirot). Miss Juliewas a late-career passion project, a surging psychosexual thriller adapted from Strindberg by Alwyn himself. That makes it sound self-indulgent, but Alwyn was an absolute pro and Miss Julie is as taut as a bowstring. Revealingly, the first conductor to record it, back in the 1970s, was Vilem Tausky, who studied with Janacek. Its champion this time around is Sakari Oramo, a conductor who takes British music too seriously to play mediocre scores. This recording from Chandos Records is an uncompromising statement of belief, gloriously sung, unsparingly characterised and stylishly played by the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

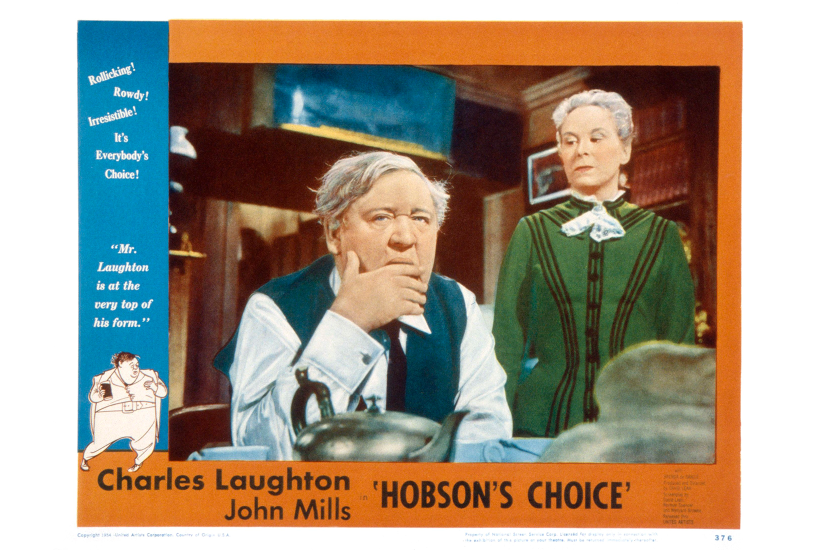

Of course, an inspired score is no guarantee of a dramatically effective opera. It’d be unwise to judge either work until we’ve seen it on stage, though the sheer craftsmanship of both composers is surely a good start. Their cinematic training is audible in every bar. The Dancing Master sounds as though Arnold wrote it at one sitting, with the libretto sparking ideas on the wing, and a glance at his catalogue for 1952 (when, in addition to the opera, he composed 11 full-length film scores, including David Lean’s The Sound Barrier) suggests that this was exactly the case. He later recycled some of those ideas back into the movies. A whimsical gavotte for a French fop reappears, harrumphing on woozy brass, as Charles Laughton waddles drunkenly through Hobson’s Choice (1954).

The opening bars of Miss Julie, meanwhile, have the same restless, grab-you-by-the-throat urgency that Alwyn brought to the main titles of A Night to Remember and Reed’s The Running Man. Both composers know how to tell and support a story, often with startling economy. The writing in Julie’s big entrance scene is chillingly spare, true to Alwyn’s stated belief, gleaned from long studio experience, that ‘without silence, the composer loses his most effective weapon’. Think of that as the library music chunters ceaselessly away over the next big BBC documentary or Netflix sensation. Plenty of 21st-century screen directors — and quite a few aspiring opera composers — might learn something from the musicians who defined British cinema. Either of these recordings would be a great place to start.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in