Scottish politics tends to go through long bouts of single-party dominance. In the 19th century, the Liberals were in charge. After the war, Labour reigned unchallenged, which is why, in 1997, it drew up a devolution settlement on the assumption that Scotland would always be its fiefdom. But Scottish Labour then imploded. The Scottish National party is now the only game in town.

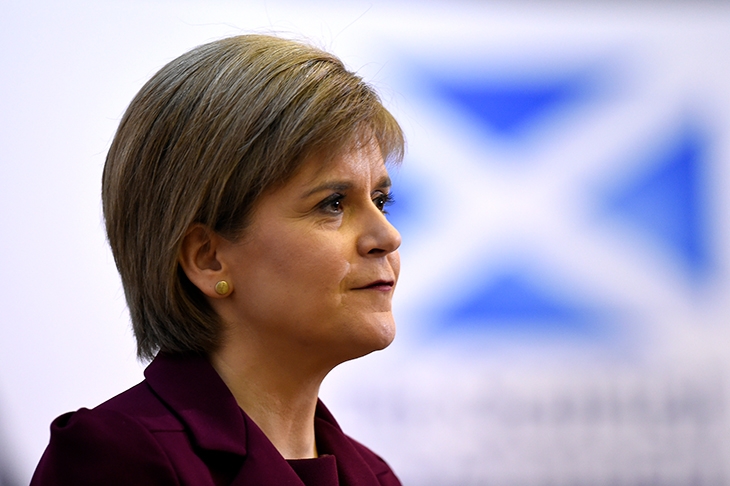

Yet there are signs Nicola Sturgeon’s party is stumbling into the pitfalls that await all parties who spend too long in office. Incumbency eventually renders even the most alert and focused political practitioners complacent. Like Scottish Labour before it, the SNP has become arrogant, secretive and controlling. Parties are at their strongest when they can see the potential for their own defeat. The SNP can no longer imagine Scotland being run by anyone else.

Lacking robust opposition at Holyrood, the nationalists fight each other instead. The sacking of Joanna Cherry this week from the party’s frontbench at Westminster was a ruthless strike against an internal critic who, in a normal party, would have been punished with a few off-the-record briefings to the press. But the SNP is not a normal party. It operates more like a bloc vote.

Whether at Holyrood or Westminster, elected representatives almost never vote against the party. The rule book for MPs mandates that ‘no member shall… publicly criticise a group decision, policy or another member’. Cherry had become open in her misgivings about Sturgeon’s leadership. She was particularly concerned about the SNP’s almost total embrace of the transgender agenda. She has now paid the price.

The devolved government in Edinburgh is easily the least scrutinised ministry anywhere in the UK, if not further afield. The Scottish parliament lacks the structural robustness of the House of Commons. There is no revising chamber. Committee chairs are handpicked by party whips and there is a near-absence of checks and balances on any executive. An apparatus designed by a naive Labour government for its own benefit now sits in the hands of a party dedicated to breaking up the Union.

Last month, the SNP published its ‘roadmap to a referendum’ ahead of May’s devolved elections. Should it win, the party will legislate for another referendum on independence — despite the fact that only the UK parliament has the legal authority to do so. The destabilising effect of a devolved legislature holding a Catalan-style rogue referendum in defiance of the sovereign parliament can scarcely be overstated.

But nothing exemplifies the impunity with which the SNP rules like the Alex Salmond inquiry. Its origins, and the whole affair, are sinuously complex but there are some firm facts. The Scottish government opened an investigation in 2018 into claims of sexual misconduct against Salmond. He sought a judicial review in which the Scottish government’s probe was found to be unlawful.

Salmond now claims a witness was told by a government adviser that, although they might lose the judicial review, they would ‘get him’ in a criminal trial. (He was tried and cleared on 13 counts of sexual assault two years later.) A parliamentary inquiry set up to review the Scottish government’s conduct is entering its final weeks. The chair, a nationalist MSP, has complained bitterly of ‘obstruction’ and had to invoke never-before-used powers to compel the Crown Office to hand over evidence. Ministers have refused to provide their legal advice on the Salmond investigation and have denied permission for requested witnesses to appear.

The question is whether Sturgeon misled parliament about what she knew, and when. Specifically, why she was so slow to tell civil servants about an April 2018 meeting with Salmond to discuss the allegations. Her husband — and the SNP’s chief executive — suggested the tête-à-tête was government business and therefore he, a party employee, was not involved. The inquiry has invited him back to explain the inconsistency with his wife’s evidence. He has declined.

A devolved government threatening rebellion against the central authority. The most serious accusations levelled about the conduct of public officials. A ruling party investigating claims against itself. One can imagine what would be said if this was happening in another country. Yet the SNP benefits from weakness from all quarters. The Prime Minister seems to have settled on a strategy of fitful ventures north of the Tweed, as though the occasional busman’s holiday is a response equal to the peril in which the UK constitution now finds itself.

Downing Street urgently needs a strategy to secure the Union. But an even more immediate challenge confronts the Scottish parliament, which is being treated with contempt. There is another option: a judicial inquiry into what Sturgeon knew and when she knew it. It is the only alternative to a Scottish parliament committee that will not get to the truth because it was never meant to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in