‘Tencent Wykeham’ has a ring to it. It captures how easily British universities can be bought. It is the new name for what was until now the Wykeham Professorship of Physics at New College, Oxford, now acquired by the huge Chinese techno-conglomerate Tencent for £700,000. William of Wykeham founded New College and Winchester in the 14th century. ‘Tencent Winchester’ next? The problem, which Oxford seems to ignore, is that Tencent acts for the national security interests of the Chinese Communist party. It propagandises too: for Xi Jinping’s address to the 19th Party Congress in 2017, it brought out a mobile game called ‘Clap for Xi Jinping: An Awesome Speech’. Our universities seem utterly confused about relationships with China, which is not wholly their fault, since the Cameron ‘Golden Era’ of uncritical adulation is still recent. But they have been so slow to develop a coherent approach. It is not that proper academic contacts should be banned: real learning takes place in both countries. It is that there is no basis of trust. Our universities need to understand that China spies on its own students abroad, steals secrets, by professional espionage and informal means, from research here, and skews British university work to cast the CCP in a favourable light, as with the China Centre and Dialogue Centre at Jesus College, Cambridge. There is little due diligence, and therefore no confidence. A small example, this week. King’s, Cambridge now has three research fellowships to study the history of the Silk Roads. A respectable subject, but the project must require a lot of money and King’s will not reveal the donor’s name. Given that China uses the Silk Roads for soft promotion of its imperial Belt and Road Initiative, one needs to know who is paying and what terms he demands for doing so.

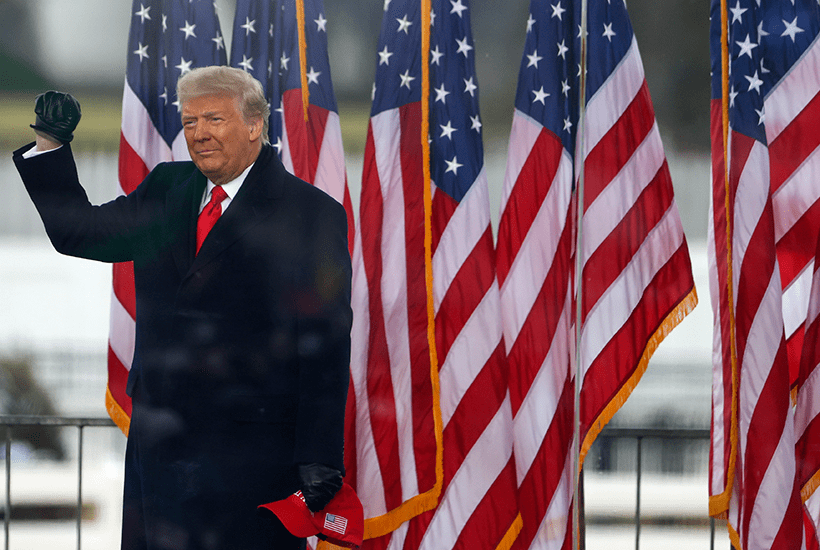

As Donald Trump faces trial in the Senate, part of the charge is that, in his notorious speech on 6 January, he urged his followers to fight: ‘And we fight. We fight like Hell and if you don’t fight like Hell, you’re not going to have a country any more.’ If you read the full transcript of Mr Trump’s words (an exhausting task), you will certainly find the word ‘fight’ cropping up a lot — (re. Republicans) ‘we have to primary [sic] the Hell out of the ones who don’t fight’; (re. the media) ‘They’d argue with me, I fight. So I’d fight, they’d fight. I’d fight, they’d fight. Boop-boop’. And so on. But if the exhortation to fight is now seen as evidence of insurrection it will — excuse my fighting metaphor — hole political rhetoric below the water-line. Where would go Hugh Gaitskell’s cry to ‘fight, fight, and fight again, to save the party I love’? What would we think of Peter ‘I’m a fighter, not a quitter’ Mandelson? And can it be right that President Joe Biden, in his inaugural address, was allowed to speak of ‘uniting to fight the common foes we face’? Perhaps the only way to get political leaders to stop the fighting talk is to persuade them that it belongs to the defeated. ‘I shall fight on. I shall fight to win,’ declared Mrs Thatcher the day before she resigned. In his 2017 inauguration speech following his 2016 victory, Mr Trump used the word ‘fight’ only (I think) once. In his 6 January speech this year, he used it or its derivatives about 20 times. Loser!

From the draft of my Note last week about nomenclature style changes in the Times, I removed a speculation that the paper would soon call the Queen ‘Elizabeth Windsor’. I decided that the paper’s new style rules, inelegant though they are, did not justify my fantasy. I was not wrong about the stylistic tendency of the age, though. On Sunday, the Observer ran allegations that the Queen, in the 1970s, had lobbied the government to change the law to ‘hide her private wealth’. On second mention in the story, the Queen became ‘Elizabeth Windsor’. This was a fascinatingly doctrinaire decision, since almost no one on Earth calls her Elizabeth Windsor. How long before Queen Victoria becomes ‘Victoria Saxe-Coburg-Gotha’ (at second mention)?

Friends who recently cancelled their National Trust family subscription because of its insulting treatment of its past benefactors received the current standard reply from the Trust: ‘We want everyone to feel welcome at our places and no one to feel that their stories or histories have been marginalised, ignored or overlooked.’ Perhaps sensing that this might not be persuasive, the letter added, ‘As you pay annually, we are able to offer a 25 per cent discount off your next renewal fee, if you feel that this would help?’ So the Trust is admitting that its wokery has made membership a quarter less valuable. I would put the percentage higher: no one feels more ‘marginalised, ignored or overlooked’ by what is happening than the average member.

Pausing occasionally to look out at the snow, I sit and read Juliet Nicolson’s vivid new book about the great winter of 1962-3. As its title Frostquake suggests, Juliet argues that those ten weeks changed Britain from stuffy to groovy. She may well be right, but my six-year-old’s memory of the time is entirely different. On the same Boxing Day on which the Nicolsons gave a tea party for the village at Sissinghurst with the recently widowed Harold Nicolson offering the guests ‘nuts, charm and respect’, I was about ten miles away, running round the garden in the dark at a friend’s birthday party. I hit my face hard on a gatepost but, as we drove home, I forgot the pain because the snow began to fall. It lay till March. We lived near the famous 21ft snowdrift which Juliet mentions. We sledged incessantly on snow that grew icier and therefore thrillingly faster as the weeks passed. All but one of the taps in our house froze. For me, this was an enchanted time which I passionately did not want to end. The melt was most melancholy, not a moment of hope. Only children think this way.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in