Rachmaninov’s First Symphony begins with a snarl, and gets angrier. A menacing skirl from the woodwinds, a triple-fortissimo blast from the brass, and then the full weight of the strings, hammering out one of those doomy Russian motto-melodies like lead boots dragging you to the bottom of the Neva. ‘Vengeance is mine; I shall repay’ glowers the epigraph that Rachmaninov inscribed at the top of the score, and you’d better believe it. The symphony’s première in 1897 was a disaster that stunned the 23-year-old composer into near-silence. And no question, when the gong roars out at the climax of the finale — on the way to one of the most savage endings in the 19th-century repertoire — it’s easy to imagine the bronze portals of the Inferno swinging open beneath the whole of Russian music.

There’s a new recording out by the Philadelphia Orchestra under its hipsterish music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin, and if any orchestra has what you might call a Rachmaninov tradition, it’s the Philadelphia. This is the ensemble that the composer himself conducted during his long exile, and for which he wrote his last major work, the Symphonic Dances, in 1940. ‘Years ago I composed for the great Chaliapin,’ he told them. ‘Now he is dead and so I compose for a new kind of artist, the Philadelphia Orchestra’ — a line which, had Deutsche Grammophon’s PR department been a bit more on the ball, would surely have been plastered all over this new release.

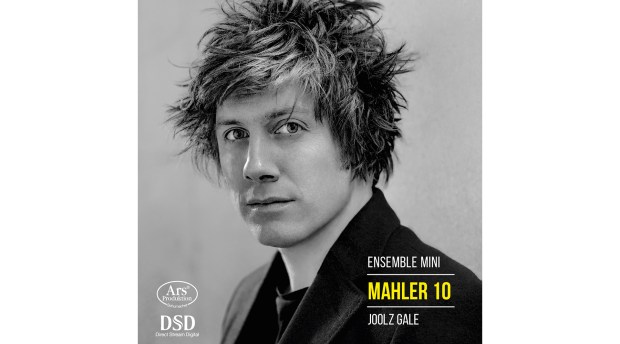

But anyway, the remarkable thing is that it’s happening at all. This sort of recording, I mean: blockbuster symphonies by Dead White European Males, conducted by superstar maestros on major labels. The classical recording industry is basically kaput, or so we’ve been hearing since at least the mid-1990s. The repertoire is overexposed, and the big-beast conductors — the kind who could sell an album on little more than a Continental-sounding name and a moody cover photo — are extinct. Well, not if my inbox is anything to go by. The economics of the big classical labels are equal parts magical thinking and brute pragmatism, and it’s unlikely that anyone is getting rich from projects like these. But to misquote Adam Smith, there’s a lot of ruin in a record company. Someone, somewhere, is doing a cost-benefit analysis on this stuff and concluding that the figures still somehow add up.

So here in the spring of 2021 we have Nézet-Séguin conducting Rachmaninov in Philadelphia and Andris Nelsons recording a double-disc set of Bruckner’s Second and Eighth Symphonies with the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra, with Wagner’s Meistersinger prelude as the merest amuse-bouche. That’s a lot of C minor and C major to be getting on with, and if a complete Bruckner cycle on Deutsche Grammophon isn’t sufficient proof of the industry’s refusal to shut up and die, Nelsons is also halfway through recording all 15 Shostakovich symphonies across the Atlantic in Boston. Meanwhile in the UK, the big recording of the year (and judging from the level of PR activity behind it, someone definitely thinks it has legs) pairs Sir Simon Rattle and the LSO with the French violinist Renaud Capuçon in Elgar’s Violin Concerto.

Ah, but they’re not Karajan or Bernstein or Solti, are they? Can these kids (this is classical music: many still regard the 66-year-old Rattle as a punk upstart) possibly compete on such well-trodden ground? That depends. At the very least, the deep sunset glow of the Gewandhaus’s horn section under Nelsons puts the lid on the persistent, cloth-eared notion that modern orchestras all sound alike. Is the pairing of a restless-sounding LSO under Rattle with Capuçon’s Kreisler-like virtuosity one for the ages? That’s for the ages to decide. For now it’s a sweeping, charismatic performance, while the coupling — Capuçon and Stephen Hough, playing Elgar’s 1918 Violin Sonata with a lightness and sense of fantasy that evokes Debussy’s near-contemporary late sonatas — opens an intriguing new perspective. Elgar as Francophile? Why not? Ravel loved steak and kidney pudding, didn’t he?

In Philadelphia, Nézet-Séguin launches Rachmaninov’s symphony as though he’s brandishing a fist. It’s brisk, it’s moody, but it’s undeniably sincere, with the fabled satin sheen of the Philadelphia string section (yes, that endures) glinting on the blunt edges of an interpretation that ends up closer to The Rite of Spring than Brief Encounter. Coming straight after the symphony, the Symphonic Dances sound more surreal than ever, their last note (a fading, jangling gong stroke) making an unambiguous connection between that doomed youthful symphony and the ageing emigré in 1940s America: a stranger in a strange land, salvaging the melodies of a lost Russia for an orchestra that even today can do big-band pizzazz as effortlessly as that luxury string sound. Worth a spin? I’d say so. It’s still their music, after all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in