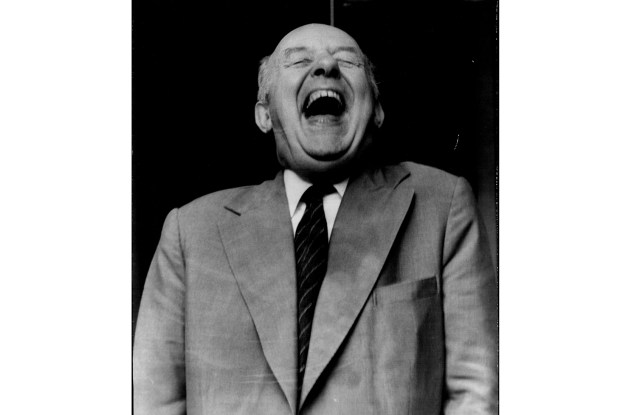

Think back 12 months to when you first felt the pandemic. Not when you first read about Covid-19, but the moment of impact — the lurch in the stomach as it hit you that this time, it really wasn’t going to be OK. For Emma Cook, a freelance stage manager on the John Cleese farce Bang Bang!, the moment came during a rare week off. ‘I was sitting in a restaurant near the Bush Theatre in London, waiting to go and see The High Table, and I got a message from a friend who had just flown back from overseas: “Why are the theatres all closed?”. I thought, no they’re not, I’m about to see a show. So I walked over to the theatre and they told us: “No, sorry. We’ve had to stop everything.” And that was when Covid suddenly became big and real.’

The rest — well, we all know the story, or at least we do now. ‘We got an email from our producer round about the 18 March, saying: “We’ve had to pull the next couple of dates, but we’re hopeful that in a month or two we’ll be back on the road again,”’ says Cook. ‘And then, national lockdown. The world stopped.’ It still hasn’t restarted. As early as last August, Equity and the Incorporated Society of Musicians (ISM) warned of an ‘exodus of talent’ from Britain’s entertainment sector. Equity reports that some 26 per cent of its members are already working outside the industry, with 16 per cent considering quitting altogether. Figures from the ISM suggest that ‘64 per cent of UK musicians are thinking about leaving the sector’.

There’s a difference, of course, between thinking and doing. Certainly, though, freelance arts workers have fallen in disproportionate numbers through loopholes in the Chancellor’s support schemes. ‘Essentially, 70 per cent of the theatre workforce is self-employed,’ says Paul Fleming, general secretary of Equity. ‘Actors, technicians, anyone that’s part of the actual physical putting-on of a production — it’s a model that successive governments decided to embark upon.’ He talks of a ‘pandemic of precariousness’ dating back to the Blair era, with governments repeatedly funding infrastructure over production costs. That’s fine while the sun shines. The problems start once the balance-sheet mindset carries over into the current shutdown, and tries — and largely fails — to grasp the realities of careers that don’t correspond to Treasury tick-boxes.

‘The average age of an Equity member is 28,’ says Fleming. ‘Many of those people don’t have three years’ worth of tax returns. It’s also not uncommon for somebody in theatre to have done a well-paid job in one year that tips them over a three-year average — so they don’t get any support. Well, of course, that fee was intended to last them a decade.’ According to Philippa Childs, head of Bectu, ‘You might be talking about someone who works in hair and make-up, or costume and wardrobe, who is engaged just for a film production or a theatre run. Quite a lot of those people found that when the music stopped, they fell through the gaps.’

It’s probably too soon to say whether the damage is permanent. Emma Cook is holding out for the postponed West End transfer of Life of Pi, which she stage-managed at the Sheffield Crucible — ‘that’s a show that’s definitely not going to open until they know for sure that it’s not going to shut down again’. Until then, she’s working as a driver for the Royal Mail. Karl Lutchmayer, a pianist admired for his Busoni, is packing online orders for Sainsbury’s, and quite enjoying it. ‘Coming from the Conservatoire sector and from classical music more widely, I can honestly say that I’ve never been managed so well. I’ve been really shocked at what a great job it is.’

Still, both of them intend to return to the arts. It’s quite difficult, in fact, to find theatre professionals who’ll admit to having quit outright. The ‘resting actor’ is a cliché based in truth; lean patches and temping are an accepted part of a theatrical career. But the shutdown has forced some experienced pros to reappraise a once-viable livelihood. Michelle Black has been a magician, a cruise ship singer, and a children’s entertainer; now she’s a PA for a mental health charity. ‘It was when this year’s Hartlepool panto got pulled,’ she says. ‘That was a big, ominous “Oh no”.’ She still hopes to stage her Julie Andrews tribute show, but regular non-theatrical employment has given her a security she doesn’t intend to relinquish. ‘After all those years of two-month contracts here, one day filming there, having a pay cheque every month has been amazing.’

And for younger professionals, Covid has exposed the instability of their chosen career right at the outset. Chiara Beebe worked at an artists’ agency in London before concluding that a different sector might offer comparable rewards with appreciably less risk of — say — your entire industry being closed down overnight. ‘Most of last year we were dealing with cancellations,’ she says. She’s relocated to Guernsey and has moved permanently into FinTech. Charlotte Evans, like many musicians in their twenties, had a part-time job while she worked to establish herself as a freelance oboist. Now she’s joined the Civil Service. ‘Suddenly there was no work, and I had a lot of time to reflect on whether music was actually making me as happy as I had thought. And even if I did work really, really hard, what is the industry going to look like after Covid?’

That’s what we’re about to find out, perhaps in ways that won’t be immediately obvious. Every orchestra manager had Bell Percussion on speed-dial — the UK’s biggest hirer of percussion instruments, servicing everyone from the LSO to Coldplay. Need a xylorimba or a set of tuned taxi-horns? Bell would get it to you before tomorrow’s rehearsal. Not any more: they closed for good just before Christmas. ‘The moment, for me, was in July, when the government announced that £1.57 billion arts bail-out,’ says Bell’s managing director, Mike Perry. ‘I had a quick look and thought, we’re not going to qualify for that. And all the time the Chancellor was saying: “The furlough’s being switched off at the end of October.” So I pulled everyone together, and said: “Look, this is the situation. I’m going to start a redundancy process, because I need to get you guys back on the job market.”’

Perry’s 11 employees have all now found new jobs. Thousands of instruments are in store in Dorset, and Bell’s warehouse in Chiswick has been rented out as a distribution hub for an online delivery service. ‘There are discussions about bringing Bell back in a different form, in a year or so,’ says Perry. ‘But it won’t be as big. How many people will be wanting to hire instruments? I used to say that Bell would only really get into trouble if everybody played Mozart for a year. Unfortunately, the pandemic is the equivalent of everybody playing Mozart for a year.’

He makes it sound almost bearable. That’s what the performing arts do — they create illusions to make life feel better, or at least more comprehensible. ‘I stilI think the creative industries will come back with a huge bang’ says Philippa Childs. Justified optimism, or an industry professional insisting, despite everything, that the show must go on? Expect euphoric press coverage as (fingers crossed) venues start opening again from mid-May. ‘The next few months are critical,’ says Paul Fleming. But in time, the biggest long-term loss might prove to be the illusion, connived in by politicians and performers alike, that a performing arts career was ever secure. The plaster has been ripped off. But if the bleeding can be staunched, there’s still a chance that Britain’s performing arts might end up in a more resilient — if less confident — place than before the curtain came down.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in